It’s that time of year: a thick, oppressive heat blankets everything, people huddle inside air-conditioned homes, offices, shops and cafes for respite—and COVID is surging again.

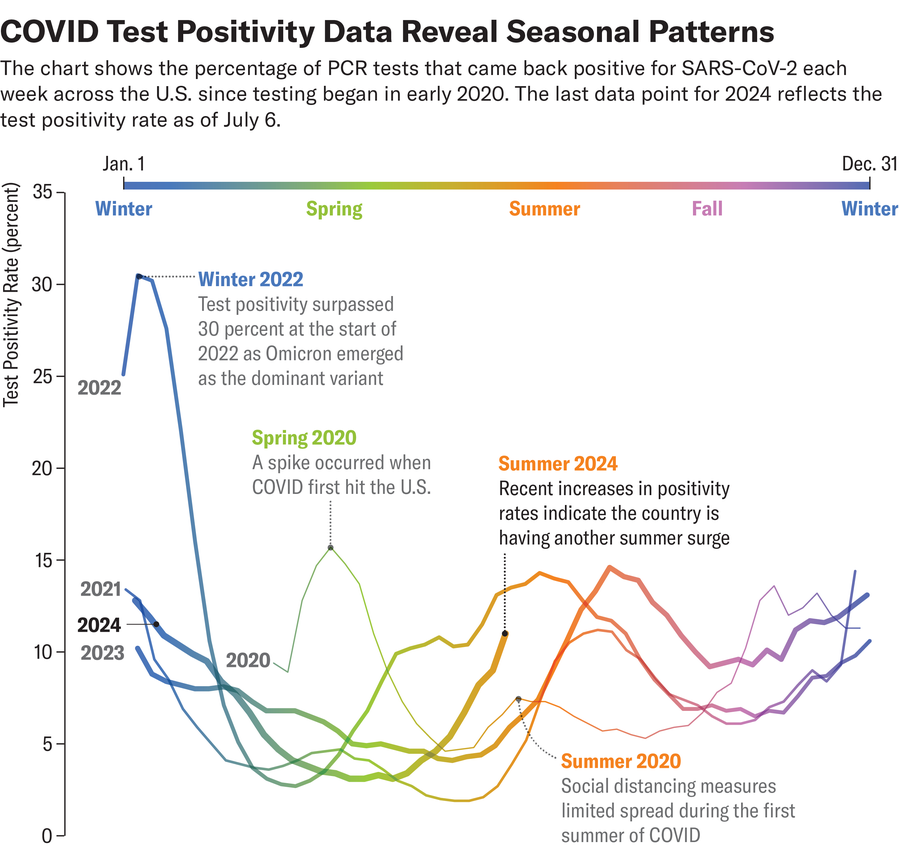

Levels of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, have increased in wastewater samples across the U.S., with the biggest uptick in the West. The percentage of positive tests—though not a perfect metric because people aren't testing as much—has also increased, but hospitalizations have remained relatively low. Most viral respiratory infections, such as influenza, peak in the winter. But for the four years that SARS-CoV-2 has circled the globe, it has caused peaks not just in winter but every summer, too. The question is, why?

Amanda Montañez; Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Possible reasons for the summer COVID peak are complex, but they fall into three main categories: characteristics of the virus itself, characteristics of its human hosts, and environmental factors.

SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve new variants. One rises to the fore every six months or so, according to Peter Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who specializes in infectious diseases. In recent weeks several new subvariants of the virus’s Omicron variant have emerged as dominant—including the so-called “FLiRT” variants (such as KP.2 and KP.3), as well as a newer variant called LB.1. These variants may be slightly more transmissible or better at evading the immune system than previous ones, Chin-Hong says.

Human behavior and the environment are other likely drivers of summer surges. During the summer, many people gather for events, travel for vacations or simply spend more time inside to beat the heat. The Northern Hemisphere winter has a string of holiday gatherings that are perfect for spreading disease; likewise, “in the summer, it’s Father’s Day, graduation, Fourth of July and then summer travel,” Chin-Hong says. “It’s kind of a like a one-two-three punch.”

“We know that nearly all [COVID] transmission happens indoors, in places with poor ventilation and/or poor filtration,” says Joseph Allen, an associate professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and director of the Harvard Healthy Buildings Program. “One hypothesis is that these building factors and human behavior are driving the summertime increases in cases.” Although many offices or other large buildings have an HVAC system that can pull in fresh air from outside, many houses and apartment buildings with window-mounted air conditioners do not. Instead these ACs simply recirculate stale, virus-laden air inside a room.

Some studies have shown that humidity and temperature can also affect SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The virus is thought to survive best when humidity and temperature are low because cool and dry air holds less moisture—so virus-trapping microscopic droplets can remain airborne longer before settling on the ground. But these factors are probably less significant than human behavior and the characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 itself. Early in the pandemic, scientists thought summer might slow COVID because the virus is exposed to higher heat and more solar ultraviolet light.“ But look at Florida and tropical countries,” Chin-Hong says. “There was no break.”

It’s a persistent mystery why COVID spreads so efficiently in the summer as well as winter, whereas flu tends to be mostly a winter disease, says Linsey Marr, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech, who specializes in aerosol transmission of pathogens. “I’ve studied the seasonality of the flu for many years, and we have some hypotheses about why it peaks in the wintertime,” Marr says. One is that the flu virus survives better in dry conditions. Another is that our immune system is weaker in winter, and a third is that heated buildings are tightly sealed and recirculate contaminated air. In the summer, some of these conditions apply in cool, air-conditioned buildings—yet we don’t see a summer flu peak. SARS-CoV-2 appears to be hardier than the flu virus, Marr notes, so it might simply be able to survive conditions that flu can’t.

With climate change bringing more frequent and severe heat waves to much of the U.S. and the world, people will likely be spending even more time indoors in summertime—and so will SARS-CoV-2. This year’s summer surge appears to have started on the West Coast, which has already had several weeks of severe heat.

And then there’s the human immune system. People’s immunity to COVID may have waned since the last time they were vaccinated or infected in the fall or winter, making them more susceptible to getting sick. Fortunately, immunity from past exposure, in the form of memory T cells, keeps most people from getting severely ill. But waning antibodies mean people can still get infected.

Earlier this year the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention encouraged people aged 65 and older to receive a second booster of last fall’s COVID vaccine. But fewer than a quarter of adults have even gotten a first booster since last fall. Chin-Hong recommends that if you haven’t been vaccinated in the last year, you should do so now. Older adults—especially those who are immunocompromised, planning a trip or attending a large gathering such as a wedding—should consider a second booster, too. And the Food and Drug Administration recently authorized a new version of the vaccine for the fall that is targeted toward the FLiRT variant KP.2 or its predecessor, JN.1.

Of course, there are other steps people can take to avoid summertime COVID, and many of them will sound familiar: masking, breathing cleaner indoor air by increasing ventilation and filtration, and avoiding crowded indoor spaces.

Today, four years since COVID first emerged, most people have some level of immunity to SARS-CoV-2 through vaccination, infection or both. And the virus is not nearly as deadly as it once was (although it still poses a danger to chronically ill or immunocompromised people, and long COVID is always a risk). At this point, Allen says, we’d be better off finding more structural solutions, such as redesigning buildings to allow for both climate control and clean, healthy air, instead of having to choose between them. “We’ve been fed this false narrative that it’s energy efficiency or healthy indoor air,” Allen says. “I reject that. And everyone should reject that. We can have both.”