This episode of Lost Women of Science was created with funding from AstraZeneca.

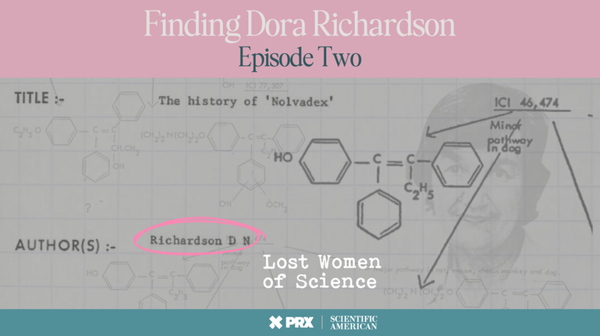

Although initial clinical trials of tamoxifen as a treatment for breast cancer were positive, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) did not believe the market would be commercially viable. The company had hoped for a contraceptive pill, not a cancer treatment, and tamoxifen didn’t work for contraception. In 1972 the higher-ups at ICI decided to cancel the research. But Dora Richardson, the chemist who had originally synthesized the compound, and her boss, veteran scientist Arthur Walpole, were convinced they were on to something important, something that could save lives. They continued the research in secret. Tamoxifen was eventually launched in the U.K. in 1973 and went on to become a global success, saving hundreds of thousands of lives. Richardson’s role in its development, however, was overshadowed by a male colleague and all but forgotten.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

TRANSCRIPT

Katie Couric: Hi, I'm Katie Couric. In honor of Breast Cancer Awareness Month, “Lost Women of Science” is bringing you part two of the amazing story of Dora Richardson, the British chemist behind the groundbreaking breast cancer treatment tamoxifen. The compound that she synthesized in 1962 would not only go on to save lives, it would change the way we look at how cancer could be treated. Not as a death sentence, but as a chronic condition that could be managed through medical therapy. Today you'll hear about how that out-of-the-box thinking made a global impact, and the never before heard story of the life saving drug that almost didn't happen.

Katie Hafner: This is “Lost Women of Science,” and I'm Katie Hafner.

This is the second episode about Dora Richardson, the organic chemist who was so lost to history we almost despaired of finding enough information to tell any story at all. But here we are, in Episode Two. It's 1970, and Dora is working in the Fertility Regulation Division at chemical giant, ICI, in the north of England.

She and division head, Arthur Walpole, are investigating two possible uses for tamoxifen. As a possible oral contraceptive or as an anti-tumor agent. On the one hand, there was disappointment. Tamoxifen was not turning out to be the contraceptive ICI had hoped for. But it was beginning to show some promising results in reducing estrogen receptor positive tumors.

It was an entirely new approach. And the best word for it is groundbreaking.

Viviane Quirke: At that time, When Dora Richardson synthesized tamoxifen, there were no drugs specifically targeting the organs of the reproductive system. There wouldn't have been any.

Katie Hafner: That's Viviane Quirke, the historian we met in last week's episode.

The longstanding goal of Drs. Walpole and Richardson was to take this groundbreaking compound and test its efficacy on the people who needed it most. Those with advanced breast cancer, and that is just what they did.

At a clinical trial in 1970, tamoxifen, which went by the brand name Nolvadex, was given to 60 late stage breast cancer patients.

Katie Hafner: After 10 weeks, tamoxifen had shrunk tumors substantially in 40 of those women, with very few side effects. This was truly a breakthrough moment. No chemo, no surgery. Just anti-estrogen drug therapy. The research team was elated.

In that once lost and now found paper that we unearthed in the last episode, Dora described that early trial in 1970, and she wrote this, “Patients with breast cancer treated with Nolvadex felt capable of doing a day's work.”

For women who had been subjected to debilitating, sometimes ineffective cancer treatments, this was very big news.

Viviane Quirke: Dora Richardson describes, with some emotion, the reports they were getting, the team were getting, of clinical trials with tamoxifen in breast cancer patients. And describing how women who were able to leave hospital without being crippled by pain from their cancer was obviously very encouraging to the team.

Katie Hafner: And not only that, these results confirmed the early hunch of Drs. Walpole and Richardson: That an anti-estrogen, like tamoxifen, could mark the beginning of a whole new treatment approach.

Michael Dukes: Just to make it abundantly clear, manifestly, you know, ICI, the inventors including her had been correct back in 1963 in predicting these compounds would be useful in treating cancer.

Katie Hafner: That's Michael Dukes, a chemist who started working at ICI in 1967, just two years after tamoxifen received its patent.

Michael Dukes: My area of research did not impinge upon Dora, but I had the great fortune to be allocated a desk next to Dora.

Katie Hafner: But even with the encouraging results from that first trial in 1970, tamoxifen's development was moving at a molasses-like pace.

Michael Dukes: It was partly because of the way tamoxifen emerged and developed. By the standards of that time, it was very slow to get to clinical trial.

Katie Hafner: So where, logically, might you think ICI would go from here? Do you think they'd double down on the positive results from the breast cancer trials? Would they expand the research staff in order to understand the drug's potential more quickly?

Well, the best description of the higher ups at ICI was narrow minded. The company wanted to find an anti-estrogen to compete on the contraceptive market, and tamoxifen was not that. As the top executives at ICI saw it, the market for cancer drugs was not necessarily a lucrative one, especially in a patient population that suffered from advanced cancer.

As Michael Dukes describes it, Arthur Walpole felt intense pressure from ICI to produce results, and quickly.

Michael Dukes: He knew the facts. He knew the issues. He knew the problems. They weren't things you could deal with quickly. It inevitably took quite a long time.

Katie Hafner: So what would Arthur Walpole's bosses decide to do?

Much of Dora Richardson's once lost paper is a compendium of detailed notes on the process of isolating the isomers in the pure version of tamoxifen. That's all very interesting, especially if you happen to be a chemist, but there's a section I find even more interesting. Dora describes a meeting that she attended at ICI in which the successful results of that breast cancer trial were presented.

She wrote, “This encouraging result was not universally received with enthusiasm within ICI, as it was said the team were supposed to be looking for an oral contraceptive, not an anti cancer agent!” Exclamation mark. There are a few exclamation marks in Dora's history of Nolvadex, four to be precise, and a bit of punctuation wouldn't normally draw attention to itself, but in Dora's case, an exclamation point does, especially coming from a very quiet person.

Katie Hafner: And this one speaks volumes. It marks a sort of unfiltered version of Dora, a way that she was noting, even if it was to herself, the exasperation she felt, especially given what came next.

She wrote, “Shortly after this meeting, it was proposed that Nolvadex be dropped from development since it was never going to cover the research and development costs and bring an appropriate return to the division.”

Ouch.

Here's Michael Dukes again.

Michael Dukes: So drug sales for the treatment of breast cancer. Were very small at that time. The commercial people felt we're only going to take part of that market. So is it worth it? And that was why they were very, very lukewarm.

Katie Hafner: The mood of the research team, Dora wrote, turned from elation to despondency. But ICI hadn't planned for what came next.

Barbara Valcaccia: We actually did officially drop the project and we worked, you could say, semi-secretly to continue it.

Katie Hafner: That's Barbara Valcaccia, who was Dora Richardson's colleague and Arthur Walpole's lab assistant. As Barbara describes it, her frustrated boss went rogue. He conscripted Barbara and Dora to continue with the tamoxifen research in stealth mode.

Barbara Valcaccia: Nobody, well Dora knew about it. But nobody else knew what we were doing. And this was something squeezed into lunch breaks and coffee breaks and goodness knows what else.

Katie Hafner: The entire tamoxifen project went underground. Literally.

Barbara Valcaccia: At that time, I had a room with animals in, and it was in the sub-basement of a dark little place. I did the experiments for several months, for Dr. Walpole, and just the two of us knew about it

Katie Hafner: For her part. Dora continued making the compound needed for the underground experiments, which couldn't have been easy.

Barbara Valcaccia: Dora had managed to, was still working with us though by that time. She must have been shifted onto another project, but she still found time to do bits for us.

Katie Hafner: Arthur Walpole was affectionately known in the division as Wallop, and he had the reputation of being a brilliant scientist who could work effortlessly in both chemistry and biology. Colleagues described him as an absent-minded professor type.

Barbara Valcaccia: He was very intense in that he wanted his work done properly and evaluated properly…he wasn't a nitpicker. He just wanted to know that the work was reliable.

Katie Hafner: He wasn't a nitpicker, but he was tough. After several months of toiling in secret, Dr. Walpole gave ICI an ultimatum. The company could give tamoxifen research its formal blessing, or he could resign.

Barbara Valcaccia: He threatened to resign and the project was reinstated.

Katie Hafner: Tamoxifen research was back on. In her understated way, Dora recounted what one person running the clinical trial said at the time. ICI could not morally withdraw the drug in light of the encouraging results. ICI's motives for continuing are unclear to this day. Whether ICI leadership reinstated research because they recognized the moral imperative or because they were afraid of losing the brilliant Arthur Walpole, no one really knows.

And that April, in 1972, the company did find a reason to resume research.

Michael Dukes: Fortunately, Walpole was able to see it through.

Katie Hafner: But let's stop here for a moment to reflect. Of course, with any drug development, there are any number of reasons why a particular drug might not make it to market. But in the case of tamoxifen, which began as a treatment for women with late stage cancer and was later approved as a preventative treatment for breast cancer in high risk patients, the absence of this treatment would have been devastating to so many women who have since benefited from tamoxifen.

Indeed, it's hard to fathom what might have happened without tamoxifen. Boy do we women have a lot to thank Dora Richardson, Arthur Walpole, and Barbara Valcaccia for. Not just their determination, but their grasp of the moral imperative to keep going. It was a long uphill climb.

Barbara Valcaccia: It is really, um, something that is so effective and has helped so many people to have had to struggle to such an extent to get it onto the market.

Katie Hafner: Once the research started up again, officially that is, the team conducted more clinical trials. Some of which took place at the very hospital where Dora had visited her dying grandmother. The place where Dora was inspired to become a chemist in a cancer research lab. The researchers continued to see positive results. Tamoxifen's genius at fighting estrogen receptive breast cancer was becoming clearer.

When you read Dora's unpublished paper, you get the feeling that she knew the early story of tamoxifen's development needed to be written down, if only to make sure it was told correctly one day, just in case anyone went looking for it.

Julie James: I think a lot of science is hidden until it gets to a certain point.

Katie Hafner: That's Julie James, the archivist who combed through those 40 boxes looking for the history of Nolvadex for us. In Julie's work at the archive, she notices that researchers might look back to the moment a drug is launched, but they don't go back much further than that.

Viviane Quirke: The people that were before that point just get forgotten.

Katie Hafner: Tamoxifen's story is no different. By looking back beyond the launch of the drug on the market, we can see why the worldwide success of this drug was by no means a foregone conclusion. It was a revolutionary approach.

Ben Anderson: Well, you know, we talk about cancer in general, and we tend to think of, well, there's cure, and then there's not cure.

Katie Hafner: That's Dr. Benjamin Anderson, the former breast surgeon we met in the last episode. In his role working with the Global Breast Cancer Initiative at “The World Health Organization,” he's seen the impact tamoxifen has made on the health of women around the world. That's due, Dr. Anderson explains, to the elegance of tamoxifen's mechanism of action.

Ben Anderson: Well, tamoxifen comes from this group called Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator, SERM. What tamoxifen does is, it's a molecule, it's a medicine, and it sits on the estrogen receptor and blocks it. So it blocks the hormone stimulation of the cancer.

You're really using the biology of the cancer against it, as opposed to just doing something that kills cells. It's not just a toxic substance. It's manipulating the hormone receptor pathways to cause the cancers to either be suppressed or, or to die.

Katie Hafner: In this way, tamoxifen acts like a key broken off in a lock. It keeps that lock from being opened. This was a radical departure from the way cancer was treated at the time.

Ben Anderson: I think that what's really impressive about what Dora did, and what others who were making progress in similar areas, was just how limited their tools were for these purposes. But I think from what I understand, not only was she good at working with the medicine, but she was thoughtful about where this might go and how it might be used in the best way.

Katie Hafner: Dr. Susan Galbraith, Head of Oncology Research and Development at AstraZeneca, agrees that it was the team's ability to look at different possibilities for the compound that led to new discoveries.

Susan Galbraith: So that was what was exciting to the team.

Katie Hafner:. Their hypothesis that an anti-estrogen could work against cancer took time to prove, but it paid off in incredible patient outcomes. The more they tested it, the more encouraged they were by the results.

Susan Galbraith: And again, different from what the original idea had been behind that project, but rapid adaptation into something which was applicable. And I think it was very exciting for the team altogether to sort of see those early results.

Katie Hafner: Adaptation. That was key.

Ben Anderson: And so the recognition that tamoxifen had something beyond the fertility roles that it wasn't panning out so well for, but recognizing, say, this might do something really important in another area, that's what genius is like.

Katie Hafner: Genius is a good way of putting it, and clearly in the early development of tamoxifen there was a whole lot of genius going around, which raises the question, why have we forgotten the geniuses who were there at the very beginning?

More after the break.

Katie Hafner: And so we return to what's missing. In our last episode, Michael Dukes described Dora Richardson as an Agatha Christie-type character, and we could’ve used an Agatha Christie character to help us find her. But aside from Viviane Quirke, and us, it's not as if anyone's been looking for her. In addition to that, Dora made herself hard to find.

Michael Dukes has an idea as to why.

Michael Dukes: I think because she didn't make much noise. You know, most chemists who have made a drug then tend to, you know, make a fair bit of noise about it themselves. Probably go to meetings, you know, scientific meetings and present on it where, you know, again, Dora, I don't think, did much of that.

Katie Hafner: And if Dora is to be summed up in one word, Michael Dukes thinks that selfless is an apt one.

Michael Dukes: I think that's the best word. She wasn't looking for her own personal sort of advancement in that sense.

Katie Hafner: But selflessness alone is not enough to explain a disappearance, at least not in this case.

In 1974, as tamoxifen saw increased success in patient trials just after it was launched in the UK, someone new joined the team, a pharmacologist named Craig Jordan.

Katie Hafner: To this day, his is the name usually associated with the success of the drug, and his name is often accompanied by this description, the father of tamoxifen. Craig Jordan first came to Alderley Park as a summer student in 1967 and later in 1972, as a Ph.D. candidate. Dr. Walpole was assigned as Craig Jordan's thesis examiner, and Craig Jordan would stay close to ICI and tamoxifen for decades, working to expand its use in a growing list of patients.

But he overshadowed the people who had been on the team up to that point, including Dora. Historian Viviane Quirke has an opinion about that.

Viviane Quirke: He was publishing so much, he was drowning everybody in papers, you know?

Katie Hafner: In other words, he was drowning everyone else out. At least, that's how I'm interpreting it.

Craig Jordan would go on to write and speak about tamoxifen for the rest of his life. There's no shortage of information about how the drug was brought to market and Craig Jordan's role in that success.

But when the spotlight shifted towards Dr. Jordan, it shifted away from the team that had been pushing the research forward for 14 years before he got there.

Katie Hafner: There's no doubt that Craig Jordan had a major role to play in this odyssey, guiding tamoxifen through the lengthy clinical, legal, and regulatory battles. Craig Jordan was also a force behind the expanded uses of tamoxifen, including among younger women. But as far as we can tell, Craig Jordan mentioned Dora only briefly, if he mentioned her at all.

In a paper on the 50th anniversary of tamoxifen's first clinical trial, he cited her once. He called her, quote, “a talented organic chemist.” And that was it. Barbara Valcaccia finds this unfair.

Barbara Valcaccia: Her work was so important and she is so rarely mentioned as having anything to do with it.

Katie Hafner: And Craig Jordan had the megaphone.

Michael Dukes: That he managed to speak louder and more often, he became associated with it.

Katie Hafner: To give you an example of just how disconnected Craig Jordan was from tamoxifen's early development, there's this. In early 1975, tamoxifen was caught up in a patent dispute in the United States. Michael Dukes was there, and so was Dora Richardson. Craig Jordan was not.

Michael Dukes: I mean, the last time I saw her was at the trial in Washington, the, uh, federal circuit trial when ICI took the American Patent Office to court. We sued them for their failure to apply the law correctly, and as a result denied the tamoxifen, the 46474 patent.

Katie Hafner: At that trial, it was Dora Richardson, not Craig Jordan, who was called as a witness, perhaps for one simple reason.

Craig Jordan had not been there at the beginning. But he knew a good product when he saw it, and he knew how to position that product in the market. And for that, he deserves credit.

Barbara Valcaccia: It's just that Craig had a particular type of personality. He was a self-publicist, but he moved in on something that was going to be successful and made sure his name was associated with it.

Katie Hafner: Dr. Benjamin Anderson, who knew Craig Jordan, believes he would have recognized Dora Richardson's role, if asked.

Ben Anderson: Dr. Jordan became known as Dr. Tamoxifen, but I think he would have been the first to stand up and say, I was standing on the shoulders of others. And, uh, Dora, I think, was one of those.

Katie Hafner: When tamoxifen was finally launched in the U.K. in 1973, it was for the treatment of advanced breast cancer. It was an encouraging sign, but it didn't meet with much fanfare. An in house ICI paper stated, “Whilst it is not a breakthrough drug and is not expected to achieve major sales, Nolvadex is nevertheless one of the most significant drugs to result from the division's research program.”

You can say that again. Because today, the uses for tamoxifen have increased exponentially from that underwhelming description, along with the patient populations that it treats. Here's Susan Galbraith again.

Susan Galbraith: If you think about the impact that this particular drug has had on the outcome for breast cancer, the understanding of how we can change the, you know, the hormonal drive for that disease and led to a whole series of other drugs, a whole range of other hormonal therapies for breast cancer that this finding triggered. It's a remarkable impact.

Ben Anderson: Tamoxifen reduced recurrence rates by about half and cut mortality statistics in ballpark figure, 50%. That is a really big number in oncology.

Katie Hafner: Once it's determined that a tumor is estrogen receptor positive, tamoxifen can be prescribed. And, because it's well tolerated, it doesn't require any monitoring over the course of treatment. That makes it extremely accessible.

Ben Anderson: You know, what do you need? You need a pharmacy. And, and so, Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, uh, Latin America, you don't have to go to the super fancy hospital to get this prescription that you take once a day for five to ten years.

Katie Hafner: Dr. Anderson explains that tamoxifen is so important to global health, it's on the WHO's list of most essential medicines.

Ben Anderson: WHO created this concept of the essential medicines list. They've gone through pulling on expert opinion and knowledge. They've identified medicines that have a big bang for your buck. These are effective medicines and they're appropriate to have. It's important guidance.

Katie Hafner: Dr. Anderson believes that this kind of accomplishment is possible only when a team pushes a revolutionary idea forward.

Ben Anderson: And so it's that thinking out of the box. And I think that the work that Dora and others on this team did, they fit in that realm. And it isn't just about one person. It's about our system of science overall.

And isn't it awesome that we all get to participate in this and see the benefits when we are able to bring it to the public.

Katie Hafner: And here, Susan Galbraith of AstraZeneca echoes something that Dr. Anderson said earlier.

Susan Galbraith: We stand on the shoulders of the people that have gone before.

Katie Hafner: But wouldn't it be better if we knew whose shoulders today's scientists are standing on? Or is that just wishful thinking?

I mean, is it really so surprising not to know the developer of an effective treatment? Do I know, for example, the name of the scientist who developed the Ibuprofen I took from my headache this morning? I don't. Historian Viviane Quirke.

Viviane Quirke: The chemists who make things aren't usually the big heroes of the story, whether they're male or female.

Nevertheless, The fact that there's this female chemist, and there weren't that many, especially synthetic chemists, making a breast cancer drug needs highlighting.

Katie Hafner: That is an understatement. In his own version of the history of tamoxifen, Craig Jordan wrote, “History is lived forward, but is written in retrospect.”

That was perceptive of him. Maybe he was looking back from his perch on Dora's shoulders and failed to notice who was below him. But depending on who is looking back, it's easy to see how certain characters get completely left out. Dora Richardson, who toiled away in Lab 8S14 to synthesize tamoxifen, is essentially unknown.

Katie Hafner: On July 3rd, 2024,“The New York Times” published Craig Jordan's obituary and described him thusly in its first sentence: “V. Craig Jordan, a pharmacologist whose discovery that a failed contraceptive, tamoxifen, could block the growth of breast cancer cells, opened up a whole new class of drugs, and helped save the lives of millions of women.”

We sometimes like to say that at “Lost Women of Science,” we're not mad, we're curious. Okay, we're a little mad. So yes, we're a little angry that the newspaper of record has credited Craig Jordan with being not merely the father of tamoxifen, but its discoverer. This is what people will come to believe, but it is simply untrue.

Katie Hafner: At “Lost Women of Science,” we believe that the true origins of scientific discoveries matter. We care about getting the historical record right, and we believe that the rest of the world should care too. But why does it matter? Because the truth matters. Giving credit where credit is rightly due matters.

If a building or a street is going to be named for someone who created something important, make sure it's the right someone. Here's Viviane Quirke again.

Viviane Quirke: This is a breast cancer drug that saved the lives of women. I think the fact that it's a female chemist who synthesized a breast cancer drug is significant.

Katie Hafner: Michael Dukes describes Dora Richardson as a woman from a particular time and place that required behavior that many women today would find unimaginable and unacceptable.

Michael Dukes: She didn't, in any way, come over to me as a feminist in the sense that we're being downtrodden and all the rest of it, even though she had every reason to be. Because, of course, up until, I think, the early 70s, women in industry in Britain were only paid 80 percent of what their equivalent males were being paid.

Katie Hafner: Even if Dora wouldn't have been called a feminist, from the fragments of her life that we know of outside of ICI, we know that she was a founding member of the local Soroptimists Club. The Soroptimists are still around today and they encourage the empowerment of women through education. Michael Dukes also believes that although Dora was quiet about it, she was well aware of the pivotal role she played in the success of tamoxifen in treating breast cancer.

Michael Dukes: I think she was kept informed. I mean, it was in the press. She knew what it was achieving. I think she would have had, you know, drawn quiet satisfaction, pride, she was entitled to, you know, she had changed the planet in that sense.

Katie Hafner: Dr. Arthur Walpole retired from ICI in 1977 and he died unexpectedly six months later at age 64.

Sadly, he never got to see the full extent of his life's work. In Dr. Walpole's hometown of Wilmslow, England, just three miles from the old ICI headquarters, there's now a Walpole Way named after him, thanks to the efforts of Michael Dukes. It's a small tribute to a man who some say should have been considered for a Nobel Prize.

Katie Hafner: It is some comfort to know that Dora Richardson lived to see tamoxifen's impact on women's health. And, before she retired, she also saw ICI's revenues explode thanks to tamoxifen. Dora's history of Nolvadex states that in 1980, its estimated actual sales worldwide were 30 million pounds.

Or around 200 million dollars in today's money.

Viviane Quirke: So her unpublished history finishes with, “Oh, ye of little faith.”

Michael Dukes: “Oh ye of little faith.”

Julie James: “Oh, ye of little faith” is a last sentence. That says it all, doesn't it really?

Katie Hafner: The global market for tamoxifen is expected to reach over $712 million dollars in 2032.

When Dora Richardson retired from ICI in 1979, there was an informal send off for her. Her lab manager at the time made a few remarks thanking Dora for her service. She graciously accepted and said in response, “I have had a very gratifying and fulfilling career. Nolvadex is a once in a lifetime discovery and I feel lucky that I was in on it. I feel I have done something with my life.”

Katie Hafner: According to an ICI article, the division gave her the following going away gifts. A pair of binoculars. A radio cassette player. Some cut glass. And a book. That sounds so British. So restrained. So of its time. So small, it's almost heartbreaking.

But if there's one thing we've learned about Dora, it's that she wasn't comfortable being singled out. It's also worth remembering that Dora's lifelong dream had been to work as a chemist in cancer research. And with that in mind, I think we can feel confident that Dora's true gratification might have been felt in other ways.

Like on this otherwise ordinary day back at the ICI lab, when early trial results were coming in.

Barbara Valcaccia: It was just after lunch one day, and we were all starting to work again. Dora burst into the lab and she was so excited, and she got this paper in her hand and she said “read it, read it.” So we read it and she couldn't keep still. She was hopping from one foot to the other. She was so excited and it was a letter from a patient who had been treated with tamoxifen and had recovered from a breast tumor.

Katie Hafner: That patient was so grateful that she had written to ICI to find out who had developed the treatment that saved her.

Barbara Valcaccia: She'd sought out the information about how the drug came, came to be made or who made it. And who was the chemist who synthesized it.

And she'd actually written to the company, asking that, that Dora should be Uh, thanked for what she'd done. And Dora got this letter, and she was happy, embarrassed, delighted, grateful, because normally in that sort of work, nobody gets in touch with you, if you manage to get a drug onto the market.

You've got a drug onto the market and that's that, and you move on to something else. Uh, but somebody had taken the trouble to write in and then say thank you for doing it, and she was so happy.

Katie Hafner: When we found that long lost paper with the help of archivist Julie James, she had this to say.

Julie James: It's lovely to think that someone's took the time to look back at who actually really did the science behind it and bring her forward into the limelight. Probably a little bit too late, but yeah.

Katie Hafner: She's right. It is a little late. We wish this had happened a long time ago. And now we think of this as our little pink ribbon to Dora. A reminder about the importance of recognizing those who have made a difference in our lives. Who have, in some cases, saved our lives. And because of that, deserve our sincere gratitude.

This is a long overdue shout out to a person who made very little noise and who probably wouldn't have wanted a shout out at all. But to rediscover Dora Richardson in honor of Breast Cancer Awareness Month feels especially poignant.

Katie Hafner: Getting a breast cancer diagnosis is frightening at any time. And knowing that Dora Richardson never gave up on her research to find a better treatment, we hope, is both reassuring and inspirational.

Thank you, Dora, on behalf of all the women tamoxifen has helped, and all the women tamoxifen will help. Thank you for your patience, your courage, and your brilliant mind.

Katie Hafner: Marcy Thompson was Senior Producer for this episode, and Deborah Unger was Senior Managing Producer. Ted Woods was our Sound Designer and Sound Engineer. Our music was composed by Lizzie Younan. We had fact checking help from Lexi Atiya. Lily Whear created the art.

Special thanks go to Dr. Susan Galbraith, who's on our advisory board and who first brought Dora to our attention.

And thanks to AstraZeneca, which funded this episode. Thank you, as always, to my co-executive producer, Amy Scharf, and to Eowyn Burtner, our program manager.

Thanks also to Jeff DelViscio at our publishing partner, “Scientific American.” We're distributed by PRX. For a transcript of this episode and for more information about Dora Richardson, please visit our website lostwomenofscience.org and sign up so you'll never miss an episode. I'm Katie Hafner. See you next time.

Guests

Katie Couric is a journalist, TV presenter, podcast host, and founder of Katie Couric Media.

Dr. Viviane Quirke is a historian of science, medicine and technology with a particular focus on drug development.

Dr. Ben Anderson is a breast surgeon and former technical lead of the Global Breast Cancer Initiative of the World Health Organization.

Dr. Susan Galbraith is executive vice president of oncology research and development at AstraZeneca.

Julie James is an archivist at AstraZeneca.

Barbara Valcaccia is a biologist who worked with Dora Richardson at ICI.

Dr. Michael Dukes is a reproductive endocrinologist who worked with Dora Richardson at ICI.

Further Reading

The History of ‘Nolvadex,.’ by Dr. Dora Richardson,. Imperial Chemical Industries, May 13, 1980.

Careers for Chemists, in Imperial Chemical Industries Limited. Imperial Chemical House, 1955.

National Cancer Institute for more information about cancer, cancer research, and today’s cancer treatments.