In the early 1960s chemist Dora Richardson synthesized a chemical compound that became one of the most important drugs to treat breast cancer: tamoxifen. Although her name is on the original patent, until recently, her contributions had been largely lost to history.

In the first episode of this two-part podcast, Katie Couric introduces us to Richardson’s story, and we recount how Lost Women of Science producer Marcy Thompson tracked down the chemist’s firsthand account of the history of the drug’s development.

This document, mislaid for decades, describes how the compound was made and how Imperial Chemical Industries, where Richardson worked, almost terminated the project because the company was hoping to produce a contraceptive, not a cancer therapy.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

TRANSCRIPT

Katie Couric: Hi everyone, this is Katie Couric. As you probably know, it's BREAST CANCER AWARENESS MONTH. Every October, when those little pink ribbons start popping up, we're reminded to make an appointment for a breast cancer screening, or we're reminded to go to an appointment we already made. Those little pink ribbons make all of us part of the breast cancer community, and that support takes some of the fear of breast cancer away.

A generation ago, there were fewer treatment options for breast cancer, and there was a lot of fear. Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation were the standard. Side effects could be brutal. And outcomes could be bleak. But in 1977, a drug called tamoxifen was approved in the U. S. And it was a game changer where survival was concerned.

Katie Couric: By 1985, the inaugural year of BREAST CANCER AWARENESS MONTH, tamoxifen was declared, quote, the treatment of choice by the National Institutes of Health because of its ability to extend women's lives after surgery. It would eventually be approved as a preventative treatment, the first of its kind. Now, decades later, Tamoxifen has saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of women around the world.

Today, “Lost Women of Science” is bringing you the first in a two part series about the British chemist who synthesized tamoxifen. Her name was Dora Richardson. To be honest with you, I've never heard of her. In fact, very few people have, and there's a reason for that. Her remarkable story has never been told.

Dora was an unassuming woman in a field that was, and still is, absolutely dominated by men. Because of this, there's hardly any record of her. It's almost like she didn't exist at all. The only people who truly understood her extraordinary abilities are the people who actually worked with her, and you're going to hear from some of them today.

Those who knew Dora Richardson know firsthand the impact she made, and they all agree that she hasn't received the credit she deserves. That's about to change. This disease, which has impacted my life and most likely the life of someone you know, wasn't the same after Dora. And while BREAST CANCER AWARENESS MONTH is meant to take some of the fear away, without the groundbreaking contribution of Dora Richardson, a breast cancer diagnosis would be a heck of a lot scarier.

Now, here's a little pink ribbon of a story just for her.

Katie Hafner: This is “Lost Woman of Science.” I'm your host, Katie Hafner. Today, we're going back more than 80 years in search of the British chemist, Dora Richardson. And as Katie Couric just mentioned, she wasn't easy to find, even by “Lost Woman of Science” standards. In fact, when we started working on this story, we thought we didn't have enough material for one episode, let alone two.

It was a real head scratcher. So here's the extent of what we knew when we started out. Dora Richardson was a synthetic organic chemist. For her entire professional life, she worked at ICI, which stands for Imperial Chemical Industries, an English company that had dominated the chemical industry there since the 1930s.

In the early 1960s, she synthesized the drug that would become tamoxifen. And we know this because her name is on the 1965 patent. And going into this story, that was just about all we knew.

Viviane Quirke: Frankly, all the scientists I spoke to, none of them ever said anything about Dora Richardson.

Katie Hafner: That's Viviane Quirke, a historian of science, medicine, and technology, who's written extensively about drug development.

Viviane first heard of Dora Richardson back in the early 2000s while visiting an archive at the very place where tamoxifen was developed.

Viviane Quirke: She spent her whole career there, and she retired from there, so she was a permanent fixture. But maybe hidden away in the synthetic chemical lab, part of a team made her doubly invisible.

Katie Hafner: Doubly invisible. A female scientist in a chemistry lab. So what does it mean for someone to become that invisible? To, by all accounts, disappear? That's a question that we at “Lost Women of Science” ask all the time. Because it's one thing for a person to be forgotten. And it's another thing for a person to fall through the cracks and disappear entirely from the historical record as a result of a kind of corporate amnesia.

As time went on, and Dora's work changed the course of cancer treatment, traces of Dora herself faded away. Her once vital role as a scientist was reduced to an aside in an academic paper, but one thing remains undeniable.

Viviane Quirke: You know, there is a compound at the very beginning, there is a drug at the very beginning that isn't quite yet tamoxifen, but is on its way to become tamoxifen, and Dora Richardson was very much there at the beginning.

Katie Hafner: Viviane Quirke didn't set out looking to find Dora Richardson. As part of her postdoctoral research, she had come to Alderley Park, which had been the headquarters of ICI, because she was studying the history of drugs that treated chronic disease. And tamoxifen was one such treatment.

Alderley Park is a sprawling estate near Manchester, England that dates back to the 1500s. The main hall was badly damaged by a fire in 1931, so the estate sat empty for many years. ICI bought it in 1950 to house its new pharmaceutical division. After extensive refurbishments, it opened its doors in 1957. Back when Viviane was studying chronic disease, things were different than they are now. For starters, there was an actual archive that Viviane could visit.

Viviane Quirke: That research center was in a beautiful setting with fields, with sheep, trees. And this has given me a kind of, um, almost like an insider view of what went on in the company where Dora Richardson worked. Carried out her work, and when I went to have lunch in the main refectory with the archivist, Audrey Cooper, I had views of this beautiful setting.

Katie Hafner: By the time Viviane visited in the early 2000s, ICI had spun out its pharmaceutical business into an entity called Zeneca in 1993, and then that arm merged with the Swedish pharma company Astra to become AstraZeneca. But for a short time after the reorganization, a range of ICI's historical documents remained in the archive.

The archivist, Audrey Cooper, would prove pivotal in recovering the story of Dora Richardson.

Viviane Quirke: I think she worked there for 40 years or something. And so she knew the records, but she also knew some of the people who would come to the library. And she knew the scientists. She knew what they looked like. And she was the one who said, well, you're, you're interested in tamoxifen. Here you are.

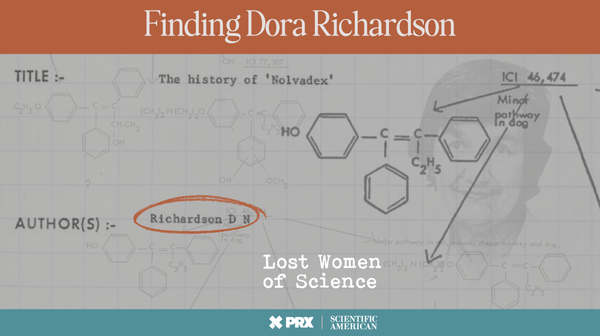

Katie Hafner: From somewhere deep in the archive, Audrey brought Viviane the only apparent copy of a paper titled The History of Nolvadex. Nolvadex, by the way, was tamoxifen's first brand name.

Viviane Quirke: It was an internal document.

Katie Hafner: A document that, as far as Viviane could tell, had never traveled beyond the archive. Or out of Audrey Cooper's sight.

Viviane Quirke: A kind of potted history, a little internal history of the early days of tamoxifen.

Katie Hafner: The author was one, Dora Richardson, and she wrote that paper in 1980, shortly after she retired. It was never published, but after she had finished writing it, Dora handed it to Audrey Cooper, along with all of her handwritten notebooks from her years as a chemist.

And it was filed away somewhere in the depths of Alderley Park. It wasn't any ordinary paper.

Viviane Quirke: It was something which expressed emotions, feelings, hopes for the future, let some of her personality come across, I think.

Katie Hafner: Viviane was not allowed to photocopy the document, but she took notes in her own shorthand.

Viviane Quirke: She appears, first and foremost, as this boffin who loves her research and her lab work, which she discovered as a young woman, she wanted to do, and indeed she did.

Katie Hafner: That word, boffin, says it all. It's a British slang term for a nerdy scientist, an experimental tinkerer. And it's not usually applied to women.

The story, or should I say, the mystery of this unpublished paper gives you a sense of just how lost Dora Richardson was. Viviane returned the paper to the archive desk. It was referenced in Viviane Quirk's writing. But only a small fraction of Dora's internal history ever made it beyond the grounds of Alderley Park.

Dora's recounting of the early development of tamoxifen, her stories of the arduous years, the obstacles, and the triumphs, all of that was returned to Audrey Cooper.

Viviane Quirke: She was very much the, the corporate person, but with a huge corporate memory of the institution through her job.

Katie Hafner: And then Audrey Cooper retired.

As if that weren't bad enough, Dora's major contribution to the development of tamoxifen wasn't given any significant attention by Viviane Quirke or by anyone else. In fact, it has been given almost no attention at all. Dora documented the purely technical processes in a brief scientific paper written in 1988, but that too stayed mainly within the company's archive.

And now, decades later, Dora Richardson had become a faded historical aside, a name on a patent, and not much more. But that paper, The History of Nolvadex, was the one place that Dora's role was clear, and once Viviane Quirke saw it, it was clear to her that Dora was instrumental in developing the drug that would go on to save hundreds of thousands of women; that Dora was an exceptionally talented scientist, and that she had been totally overlooked.

Viviane Quirke: What fascinates me is the fact that she was a woman, she was a synthetic organic chemist, and she worked in industry. There weren't very many female industrial chemists at that time. So the fact that she synthesized a drug that became so important for the health of women was a double attraction for me.

Katie Hafner: After Viviane returned that 70-page history of Nolvadex to Audrey Cooper, the paper was put back into its box, which was reshelved in the archive, and, just like that, Dora Richardson's personal story of how tamoxifen was developed went dark.

And so, we set out to find her. Because to solve the mystery of what happened to Dora Richardson's paper, we'd have to find out more about Dora herself.

Let's go back to where her story starts, as best we can, because piecing together Dora Richardson's life is a bit like trying to weave a tapestry with a single gossamer thread.

Dora was born in 1919 in Wimbledon, South London. When she was a teenager, she visited her grandmother who was dying at London's Cancer Hospital, now known as Royal Marsden.

There, the young Dora caught a glimpse of people working in laboratories. In an ICI company newspaper in 1979, Dora is quoted as saying, I supposed there is a certain coincidence that I got the urge to become a research chemist in a cancer hospital, then worked on Nolvadex. A coincidence? Probably not really.

Dora had always set her sights on working in chemistry despite the challenges. But it was far from easy.

Viviane Quirke: So she went to study chemistry at University College London. She was obviously a bright student and in a family that was quite happy for her to go and study chemistry, which wasn't a traditional destination for a bright female student. Uh, in the 1930s and 40s.

Katie Hafner: For women in the U.K. between the two world wars, studying chemistry was especially hard. Women faced a good deal of hostility. At that time, they were excluded from societies and student unions. They were a rarity among an overwhelmingly male population. Rather than risk posing a threat to their fellow male students, young women responded by keeping a very low profile.

The opportunities that were available to female chemists in school and in work were designed to keep them from coming into competition with men. In other words, they were almost always at the bottom of the pecking order.

In the final year of Dora's studies, World War II was at its height, and the daily devastation of the Blitz brought life to a standstill.

For eight straight months, London was bombarded by German planes, forcing University College London, where she was studying, to evacuate its students to Wales. Despite this, Doris stuck with her studies and she graduated in 1941. At the time, job prospects for female chemists were limited to menial positions.

And if they did land a job, they'd have to give it up if they made the mistake of getting married and having children. The only advantage in hiring women in industry at all was the price. They were paid about 80 percent of what the men made.

Even so, it took Dora almost two years to find a job. In 1943, she got an interview with ICI, an interview that took place at an air raid shelter in Blakely near Manchester.

And then she began her lifelong career at the company. She started in a division developing synthetic antimalarials, something that would have been extremely important to the war effort.

Viviane Quirke: And from then on, it seems she was working at ICI, if not the whole time from 1943, and on the basis, it seems, of the work she'd done at ICI during the war, she got her Ph.D. in chemistry from UCL in 1953.

Katie Hafner: Dora wrote her thesis on the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds, an aspect of organic chemistry still used in industry today. And from that point forward, she was known at ICI not as Dora, but as Dr. Richardson. It would be another decade before she started work on the compound that would become tamoxifen, the very first targeted therapy to treat cancer, a treatment that would change the lives of millions.

Susan Galbraith: My name is Susan Galbraith. I am the Head of Oncology Research and Development at AstraZeneca.

Katie Hafner: Susan Galbraith understands that the long and winding path to launching a new product requires a team effort.

Susan Galbraith: The reason why I've stayed in the industry for so long and been fascinated by it is it brings together many different disciplines.

Katie Hafner: In addition to the foundational science underlying their research, scientists like Dr. Galbraith, working in industrial R&D, have to understand the clinical pharmacology.

Susan Galbraith: And then you've also got to understand, um, the science and the art of drug development, of bringing that through and actually turning it into a medicine.

Katie Hafner: Each step is crucial, and the need to find effective treatments for breast cancer and to make them available worldwide couldn't be greater. The global numbers are staggering.

Ben Anderson: Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in 86 percent of countries and, uh, it's the number one or number two cancer killer among women in 95 percent of countries.

Katie Hafner: That's Dr. Benjamin Anderson. He's a breast surgeon who used to be the technical lead of the Global Breast Cancer Initiative for the World Health Organization.

Ben Anderson: Over 600,000 deaths per year by 2040, there will be three million cases globally of breast cancer and one million deaths per year. And so it is a big problem.

Katie Hafner: Now, Dr. Anderson works with a global NGO called City Cancer Challenge, whose focus is on helping cities improve access to quality cancer care. He looks back on how treatments have changed over his career.

Ben Anderson: You'd love to think that surgery fixes everything, but what we learned in the 1980s was that while surgery, or surgery and radiation, are essential for controlling the disease in the breast.

And in the lymph nodes, it's actually the drug therapy that changes overall survival. We do know that without the medicines like tamoxifen, we know that survival cannot change.

Katie Hafner: When Susan Galbraith came to AstraZeneca in 2010, she was interested in AstraZeneca's portfolio of hormonal therapies to treat cancer. She was specifically interested in the story of how tamoxifen came to be.

Susan Galbraith: It struck me that it was quite unusual to go back to the 1960s and have a woman being the chemist, um, that was synthesizing this compound.

Katie Hafner: And that wasn't the only shocker. Susan Galbraith was surprised by the fact that initially ICI was trying to enter a different market altogether.

Susan Galbraith: The history of many different drugs always includes an element of serendipity. And actually because they were looking for compounds for a contraceptive pill.

Katie Hafner: That's right. The initial research for tamoxifen, a paradigm changing cancer treatment, had actually started in a division of ICI called the Fertility Regulation Program.

And it was right about that time, in late 1959, that a veteran ICI scientist named Dr. Arthur Walpole recruited the only senior female chemist in the division to work on this groundbreaking project, Dr. Dora Richardson.

And we come to the part of Dora's mystery where, without further evidence, we would essentially have to say goodbye.

We would, quite literally, have nothing more to say. But as it turns out, we got lucky. So we do have more to say. A lot more. That's after the break.

Katie Hafner: The old ICI Archive was located at Alderley Park, that sprawling 400 acre campus in the north of England. I love the idea of Viviane Quirke visiting there as a scholar, having lunch with the archivist, gazing out at the grazing sheep, but those days are long gone. Alderley Park is now a multi-use bioscience campus for various science and technology companies.

AstraZeneca's corporate headquarters is in Cambridge, a three hour drive from there. The archive itself has been divided and moved, sent to off site locations and handled by third party vendors. Like so many aspects of modern life, what was once centralized and searchable has become dispersed. If you want to research the archive, it's available only via an internal company sponsor, which makes sense given the safeguards required to protect a pharmaceutical company's proprietary information.

And then you can access only what comes up in a search of a digital index. So when we started looking for Dora Richardson's unpublished history of Nolvadex, it didn't show up.

But that didn't stop “Lost Women of Science” producer, Marcy Thompson.

Marcy Thompson: So when you're talking, I'm going to be super quiet, but it's not because I'm not interested in what you're saying.

Okay, so go ahead.

Julie James: And you can cut bits of me out that you don't want. Right.

Marcy Thompson: Exactly right. Yeah, I can do that.

Katie Hafner: Marcy is on a Zoom call with Julie James, the archivist for AstraZeneca. Let's just say that Marcy hounded Julie for some time, first through an internal company sponsor, and then as a producer who had a hunch that the paper was there. So far, every search had turned up empty handed.

Julie James: So what I thought I'd do is I'll pick up my computer and show you all the boxes that we brought back in.

We, we called in, Oh, absolutely tons, tons of boxes, um, must've been about 40 boxes all together.

Katie Hafner: Behind Julie are stacks of research files.

Julie James: We've had a good look through them. I can show you what's inside them and show that you can, you can see the, you really don't want to see any more of them.

Katie Hafner: Julie begins to dig into a box in view of her computer's camera.

Julie James: Want me to just cut to the chase and show you what I have found that I hope is what you want?

Marcy Thompson: Yes, please.

Julie James: So, so if I just.

Marcy Thompson: Yeah, yeah. Perfect.

Julie James: So this box, um, came back, it's lots of reports, but this one's actually entitled “The History of Nolvadex,” and it's authored by Dora Richardson.

Marcy Thompson: Wow!

Julie James: And I think this might be exactly what you're looking for.

Marcy Thompson: This is insane. Can I just stop for a second and just tell you that this is so incredible. Okay. Thank you. Okay. So this is it here. Can you just hold it up? I just want to see the actual cover. There it is.

Julie James: Um, so it's Imperial Chemical Industries, PLC pharmaceuticals division, and the title is The History of Nolvadex, authored by Richardson, D. N.

Katie Hafner: It has a dark orange cover with black print.

Julie James: And this was actually written in May 1980. So she must have written this just as she was retiring, actually.

Katie Hafner: And there it was, Dora's story, waiting to be discovered in that box, deep in that archive.

Julie James: And this history has been just encompassed in that AstraZeneca sort of ICI legacy, so it will never be made public unless someone takes it to the outside world.

Katie Hafner: In other words, unless we had come along, Dora Richardson's first hand account of how she synthesized tamoxifen would have remained at the bottom of a box that was shunted from one internal corporate archive to another in the north of England as ICI's pharmaceutical arm morphed into AstraZeneca. Julie James was as excited as we were.

Julie James: Sometimes we get these jobs where we have to dig quite a bit more and be a bit Sherlock Holmesian. Um, and it's been really interesting finding out more about Dora, about those times and, uh, the whole discovery piece.

Katie Hafner: As it turned out, Dora's paper had been lost accidentally because of a clerical error.

Julie James: Now this particular one, I will update the indexing because I think it's important that it says the history of Nolvadex because I think that would have shouted out from the, right from the word go.

Katie Hafner: Imagine an oversight in indexing, and poof, a person's life's work is filed in the wrong place and their contributions are lost and forgotten. The indexing for this paper didn't include the word history of Nolvadex, and now it's not considered proprietary or protected. In fact, we have a copy of it ourselves.

Julie James: This sort of information, the history, information within it, and how Dora went about things and the problems that she had, they're good for everyone to know, I think.

Katie Hafner: You can say that again. The paper is a treasure, and it helps us tell the rest of Dora's story. As Julie says, it's good for everyone to know. And thanks to her help. Our story continues.

In 1960, ICI started a new pharmaceutical division devoted to the study of fertility regulation. The era of making love, not war was underway, and women wanted control over their reproductive health.

That same year, the American pharmaceutical company Searle had launched the first oral contraceptive approved for, quote, “married women,” according to the regulations of the day. This gave rise to a headlong rush into the market. The good news for ICI, the company had been researching hormones for some time, not as a fertility regulator, but in relation to cancer.

By then, it was already widely known that some cancerous tumors responded to hormones, especially estrogen. ICI and other companies had been interested in hormone related medicine ever since the mid 1930s, and ICI had just the man for the job. To investigate both lines of inquiry, fertility and cancer. It was Dr. Arthur Walpole.

He'd been working on the impact of estrogen on cancer since he arrived at ICI in 1937, and he'd recently been put in charge of ICI's Fertility Division. Here's Viviane Quirke.

Viviane Quirke: He starts working on cancer, on the one hand, and on hormones on the other hand. Now, the two overlap because by then it's known that some cancers are hormone dependent, in particular breast cancer.

Katie Hafner: Dr. Walpole was looking for an anti-estrogen.

Michael Dukes: An antiestrogen, is basically a drug that blocks the action of estrogen.

Katie Hafner: That's Michael Dukes, a chemist turned reproductive endocrinologist who worked at ICI beginning in the mid 1960s.

Michael Dukes: It's a complex field, because as was known from very early days, estrogen controls a huge range of biological processes, which come together in terms of pregnancy, etc. And anti-estrogen is simply a substance that blocks those actions.

Katie Hafner: But even though it would be some time before tamoxifen's potential to treat cancer would be known, the division's early work in studying anti-estrogens hit its stride in the early 60s. ICI was primarily focused on finding a drug that prevented implantation, what we'd now call a morning after pill, based on the profile of an antiestrogen called clomiphene.

It was a painstaking process and very much a team effort.

Viviane Quirke: They had a multitude of staff whose job it was to transfer chemicals from one place to the other and then going back to, uh, the bench and working on the chemistry, modifying the molecule.

Katie Hafner: Dora Richardson worked in Lab 8S14. There, she isolated the compound's isomers in a process called fractional crystallization.

Viviane Quirke: This involves six successive steps. What she does to separate these isomers so that the best isomer for the desired effect to crystallize the compound and separate out the two isomers was considered as a considerable feat.

Katie Hafner: The chemistry was difficult, and the continuous adjustment of Dora's work required communication with the team working on the biological side. The goal was to prepare a solution that could be tested on animals to find out if it stopped fertilized eggs from implanting in the womb.

Barbara Valcaccia: And we would prepare, prepare the animals, dose the animals, and then do whatever tests were necessary to find out whether it worked or not.

Katie Hafner: That's Barbara Valcaccia. Beginning in 1960, she was a lab assistant who worked on the biological side of the tamoxifen team. She worked with Dora Richardson herself.

Barbara Valcaccia: She was unusual. She was, she was a rarity. Because she was quiet, but very good at her job, she, she got a, got a better, better reception than, than anybody else. And she, she deserved it. She was great.

Katie Hafner: Barbara recently turned 91 and she still lives close to Alderley Park. Although she would go on to have a 44-year career at ICI and would work on the development of two important anti-cancer drugs following tamoxifen, things were difficult there for women in the early 1960s.

Barbara Valcaccia: It was just, we were almost servants, you know. We did as we were told. We weren't expected to have opinions.

Katie Hafner: The life of a woman in science could be, let's just say, a bit bizarre.

Barbara Valcaccia: As a lab assistant, that was where I was given the job of chasing sheep down fields and doing all that sort of thing.

Katie Hafner: Barbara's laughing because her first job at ICI involved collecting sheep feces and testing it for worms.

Once she was brought into the biology side of the tamoxifen project, Barbara describes herself as a quote, “extra pair of hands”. It was better work, but the power imbalance was stark.

Barbara Valcaccia: In every group, there was a senior man and he had a load of assistants and his assistants were almost always female, and they got all the menial jobs. Um, you know, emptying the body buckets at the end of the day, and then you have to make the tea and take it in to the boss. It was that type of thing.

Katie Hafner: Dora, however, was something else altogether.

Barbara Valcaccia: For a woman to get to the level that Dora got to was quite unusual. There was one other senior woman in the place, and that was a vet.

Katie Hafner: Barbara's memory of what took place more than 60 years ago is astonishingly clear. The team was in constant contact with each other. Dora would create a compound and she would bring it down to the biological lab where tests would be performed. The initial hope was that the compound would prevent pregnancy, but they were also hoping the anti-estrogen would have other uses. It was a long process.

Barbara Valcaccia: Then we'd calculate the results, feed them back to Dora, and Dora and Dr. Walpole would decide on a on the development that should be the next line of investigation.

Katie Hafner: The line of investigation continued until finally, in 1962, the team began to see the results they were looking for. And there in Lab 8S14, Dora Richardson synthesized a compound known as ICI 46,474. Here's Michael Dukes again.

Michael Dukes: One particular batch on that critical first occasion, she did manage to get a totally pure tamoxifen, 46,474, and that was the first time she'd got two separate isomers. And it was the first time the biologists were able to look at them separately.

Barbara Valcaccia: If she hadn't been able to separate those, we wouldn't have been able to produce the drug. We wouldn't have been able to prove that it was effective. So she was absolutely fundamental to it.

Katie Hafner: In her history of tamoxifen's development, Dora simply says this: This separation was the subject of a patent U.K. 1099093. No fuss, no muss. Ever the practical boffin.

Michael Dukes: I would basically say to me, as a person, she almost came over as an Agatha Christie-type character.

Katie Hafner: Not only did Michael Dukes work at ICI, but his desk was right next to Dora's.

Michael Dukes: She was, I suppose, of average height for a lady, but she was slim, uh, dark hair. Clearly, by then, a spinster and committed spinster at the time I first met her.

Katie Hafner: Spinster was the common term given to a woman of a certain age who hadn't married.

Michael Dukes: But I think the word demure would also fit her to the extent that she was modest, self-effacing, she was not ever crowing about, you know, what she'd achieved, what the work, how the work was going.

Barbara Valcaccia: But she was very, very quiet. I don't think she had a very vibrant social life.

Katie Hafner: In fact, Dora remained single her entire life.

Barbara Valcaccia: If she'd married, she wouldn't have worked because women didn't. She was good looking and I, and you wonder why she chose to dedicate herself to looking after her mother and working in science.

Katie Hafner: We do know that Dora had a parakeet, or as the Brits say, a budgie, and enjoyed gardening and needlework. So, although her personal life remains mostly obscured, we do know what she did in her professional life to survive in a very macho environment.

Michael Dukes: At the time I joined, the place was probably teaming with would-be alpha male chemists jostling for attention and potential promotion and all the rest of it. Um, Dora didn't engage in any of that. She just quietly got on with her own area of work and was extremely effective in it. But at the same time she wasn't timid or shy. On the chemistry front, she could hold, you know, around with anybody.

Katie Hafner: She was held in high esteem.

Michael Dukes: As a traditional synthetic chemist, she was just one of the best. I would describe her as being a cordon bleu synthetic chemist, that her chemical souffles always seemed to rise, whereas mine and a lot of other people's flopped on regular occasion. Like gardening, some chemists have green fingers and can seem to make almost anything grow, work, reactions go. She always seemed to end up with crystals.

Katie Hafner: Here’s Viviane Quirke.

Viviane Quirke: She is referred to as Dr. Richardson. So she, in a sense, she almost becomes a man in the way she's referred to within the archives, which shows the high standing in which she's held. So, there is recognition also that the chemistry she was doing was quite extraordinary.

Katie Hafner: Arthur Walpole, the ICI veteran who led the division, was known to be fair, but demanding. Knowing how technically gifted Dora was, even among a sea of male chemists, he selected her to be part of his team. Here's Barbara Valcaccia.

Barbara Valcaccia: Dora was lucky in that she was working with someone who was willing to appreciate her and to give her credit. For what she did.

Katie Hafner: It's interesting to note that Barbara had been moved to Walpole's team as a lab assistant in the fertility team.

For another reason she was Protestant.

Barbara Valcaccia: The girls who were Catholics wouldn't work on the reproductive work. They wouldn't do that for religious reason. That's how I got shunted in to work with Dr. Walpole, and luckily, I got, I got to work on and do a lot of the reproductive physiology that involved tamoxifen, or the lead up to finding tamoxifen.

Katie Hafner: The team Dr. Walpole assembled, its cordon bleu chef at the center, now focused 100 percent of its energy on finding the best possible use for tamoxifen.

Michael Dukes: There had to be a useful outcome at the end. And I think Dora's was definitely, she was seeking to help produce useful new medicines.

Katie Hafner: As they headed into early animal trials, the results were frustrating. The team realized that what prevented pregnancy in mice and rats didn't work as well in women. ICI 46,474 was showing signs that it could induce ovulation. Not what you're looking for in a contraceptive. And there were indications that it could reduce tumors.

The full understanding of tamoxifen's function was not yet clear. But Dr. Walpole and his team knew the pressure was on to find a commercially viable product. They remained convinced that tamoxifen could be proven effective in fighting estrogen sensitive breast tumors. And five years after the patent was registered, they started to see some early positive results. Yes, five years later. Drug development can be a very long process. As for ICI, they were very unhappy with the initial findings. They wanted to find a contraceptive, and the clock was ticking.

Barbara Valcaccia: You know, of course, it nearly was ditched. The whole, the whole project was nearly ditched. Don’t you?

Katie Hafner: Barbara Valcaccia heard about the project's demise at a soccer match where she ran into an executive from Alderley Park headquarters.

Barbara Valcaccia: And he said to me, You know the project's dropped, don't you? And I said, No, nobody's told me. They said, Yes. It's, uh, it's dropped. It's completely, it's no good.

Katie Hafner: Barbara was shocked. When she went to work the next day, she asked Dr. Walpole what was going on.

Barbara Valcaccia: And he said, nothing.

Katie Hafner: What came next would decide the fate of millions. Tamoxifen was looking like a dead end fertility treatment, and none of the higher ups at ICI seemed to want to explore it as a cancer therapy. But Dora Richardson and the team's inner circle had not worked this hard for this long to see it stopped now.

Next time on “Lost Women of Science,” the tamoxifen project goes underground.

Barbara Valcaccia: At that time, I had a room with animals in, and it was in the sub basement of a dark, creepy place.

Katie Hafner: Marcy Thompson was Senior Producer for this episode and Deborah Unger was Senior Managing Producer. Ted Woods was our sound designer and sound engineer. Our music was composed by Lizzie Younan. We had fact checking help from Lexi Atiyah and Lily Whear created the art.

Special thanks go to Dr. Susan Galbraith, who's on our advisory board and who first brought Dora Richardson to our attention. And thanks to AstraZeneca, which funded this episode. Thank you, as always, to my Co-executive producer, Amy Scharf, and to Eowyn Burtner, our program manager. Thanks also to Jeff DelVisio at our publishing partner, Scientific American.

We're distributed by PRX. For a transcript of this episode and more information about Dora Richardson, please visit our website, lostwomenofscience.org, and sign up so you never miss an episode. And don't forget to hit that all important, omnipresent donate button. See you next week for more on Dora Richardson and the development of tamoxifen.

Host

Katie Hafner

Producer

Marcy Thompson

Special thanks to producer Sophie McNulty.

Guests

Katie Couric is a journalist, TV presenter, podcast host, and founder of Katie Couric Media.

Dr. Viviane Quirke is a historian of science, medicine and technology with a particular focus on drug development.

Dr. Ben Anderson is a breast surgeon and former technical lead of the Global Breast Cancer Initiative of the World Health Organization.

Dr. Susan Galbraith is executive vice president of oncology research and development at AstraZeneca.

Julie James is an archivist at AstraZeneca.

Barbara Valcaccia is a biologist who worked with Dora Richardson at ICI.

Dr. Michael Dukes is a reproductive endocrinologist who worked with Dora Richardson at ICI.