This spring two broods of periodical cicadas will pour out of the ground for a weeks-long stint of mating and egg laying across swaths of the eastern half of the U.S. The bugs are large and loud—but if that’s a grim picture, just consider their emergence instead as nature’s invitation to an all-you-can-eat land-shrimp buffet.

So, with some limitation, it’s okay if your dog or cat chows on a few juicy bites. You’re welcome to do so, too. After all, insects such as cicadas and crustaceans such as shrimp all belong to the same category of animals, called arthropods, which are characterized by their hard outer skeleton. And just like the shrimp that we know and love, the crunchy coating of a cicada hides a tasty nibble of protein—the sort of snack craved by countless animals and even some plants.

“Everything eats insects,” says Julie Lesnik, an anthropologist at Wayne State University. “They are the basic nutritional element that Earth gives us. They are animal-based proteins; they have all of the same benefits as beef but in a tiny, efficient little package.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

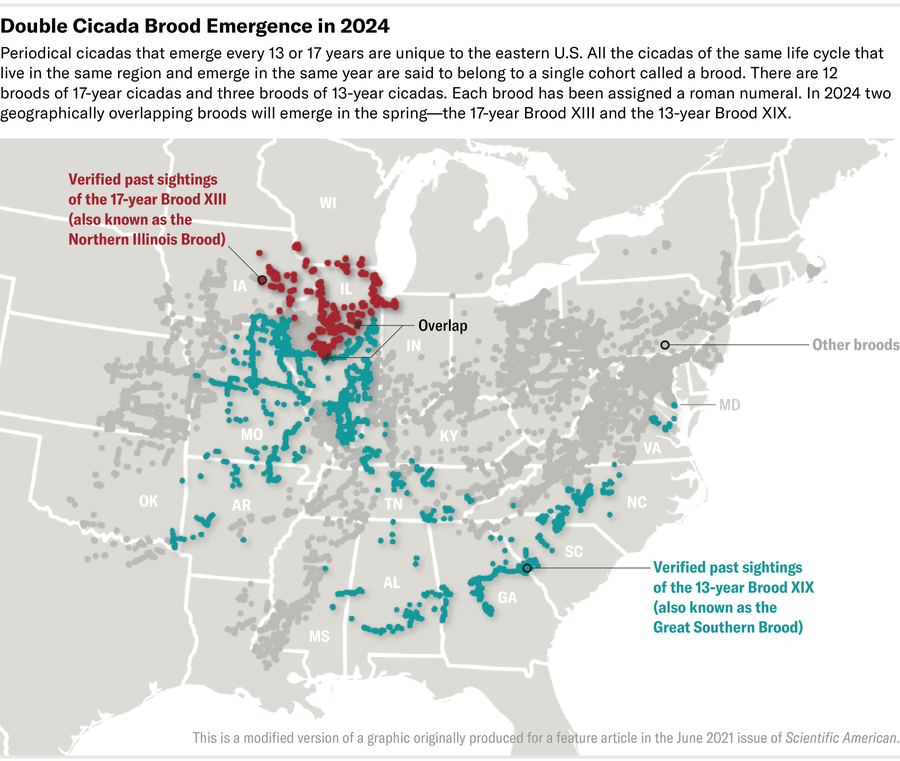

And the seven species of periodical cicadas that call the Eastern U.S. home have another appealing characteristic. Humans rarely see these bugs, which spend 13 or 17 years growing underground, but when they emerge, the insects are practically unavoidable. That’s because cicadas make use of a tactic scientists dub “predator satiety”—they come aboveground in such large numbers simultaneously that not even a forest full of hungry birds, mammals and fish can eat their way through the entire population.

Daniel P. Huffman and John Cooley, modified by Jen Christiansen

Cicadas don’t have many options for self-defense: they fly slowly and have no nasty bite, sharp spine, poison or foul taste to protect them from being eaten, leaving the insects vulnerable to countless meat eaters. In other words, for humans and our pets, cicadas are both completely defenseless and briefly plentiful.

That’s no reason to binge on the bugs, however. Enough cicadas need to survive and reproduce to ensure the next generations emerge in 2037 across the U.S. South and in 2041 in Illinois, for the 13- and 17-year broods, respectively.

Pet owners should be particularly cautious about how many cicadas their dogs or cats might munch, says Rena Carlson, a veterinarian and president of the American Veterinary Medical Association. The insects’ crunchy exoskeletons can irritate pets’ digestive tracts, and some insects may contain pesticides and similar chemicals. Eating too many—the level of which varies with the size of the pet—can result in temporary symptoms such as intestinal upset, vomiting and diarrhea, she notes. Existing intestinal problems might merit more caution as well. Carlson recommends speaking with your veterinarian about any concerns and, of course, having your pet examined if symptoms persist.

“But really the overall message is they are not going to cause a lot of harm if [your pet] eats one or two,” Carlson says. “The caution is simply against eating too many.” Keeping cats inside and dogs on leashes are both particularly wise strategies during a cicada emergence, she notes.

People in the U.S. may have less desire than their canine companions to gobble down cicadas. Both Lesnik and another anthropologist who focuses on edible insects, Gina Hunter of Illinois State University, say that the history of European colonization in North America is a strong force behind the disgust so many people living in the U.S. feel for the prospect of eating insects. Our closest living relatives, chimpanzees, have been known to devise tools to better access termites and ants, Lesnik notes, and people throughout recorded history have eaten bugs—even Aristotle, Hunter adds.

“Insects are a very widely used food resource among a vast number of world cultures—and have been since time immemorial,” Hunter says.

Cherie Sinnen

But when European colonizers came to what’s now the U.S., they began equating Indigenous habits of eating insects, lizards and the like with the behavior of people they considered uncivilized and inferior. “That narrative is what has caused us to now find [insects] disgusting—it’s not the bugs themselves,” Lesnik says. “It’s this narrative, this fear of looking uncivilized, that has been with us for hundreds of years.”

Hunter agrees that disgust about eating insects is more about our cultural narratives than insects themselves. “I think that we identify insects with filth and with decay,” Hunter says, as well as with spoiled food. “We immediately go to those natural kinds of explanations, but that does not hold up under scrutiny because lots of insects are strictly vegetarian and much cleaner eating than other items like lobsters and other bottom-feeders and other things that we highly prize nowadays as food.”

Colonization has erased many Indigenous traditions of eating insects, Lesnik and Hunter note, especially in the eastern U.S., with its longer history of occupation. One remaining story of periodical cicadas’ historical importance comes from the Onondaga Nation in what’s now upstate New York. In 1779 American troops devastated Onondaga territory under the orders of George Washington. The Onondaga were left with burned villages and little to eat in the face of a bitter winter. But in the spring the local brood of 17-year cicadas emerged in time to feed them. The nation has celebrated the cicadas, which most recently appeared in 2018, ever since.

But even white colonists with plenty to eat munched a cicada here and there, Lesnik says. She’s found stories of lumberjacks of the era enjoying them while working. “For these men in the woods, these cicadas [were] a fun snack for them. It was not a survival thing,” she says.

Today some edible insect afficionados follow in their footsteps, says Joseph Yoon, a chef and founder of Brooklyn Bugs, an advocacy group for edible insects. His only caution to potential cicada eaters is that people allergic to shellfish may also be sensitive to insects.

When collecting cicadas, Yoon notes that people should consider legal restrictions and the application of pesticides and other chemicals when selecting a harvest site. He’s also careful to inspect each insect because cicadas can carry a fungal infection that eats away the bug from its tail. “I actually hand select every single cicada [that I cook],” Yoon says. “It might seem very tedious, but it’s important to me because I’m going to be feeding them to people. In doing so, I can make sure that they’re not listless, that there’s life in the cicada.”

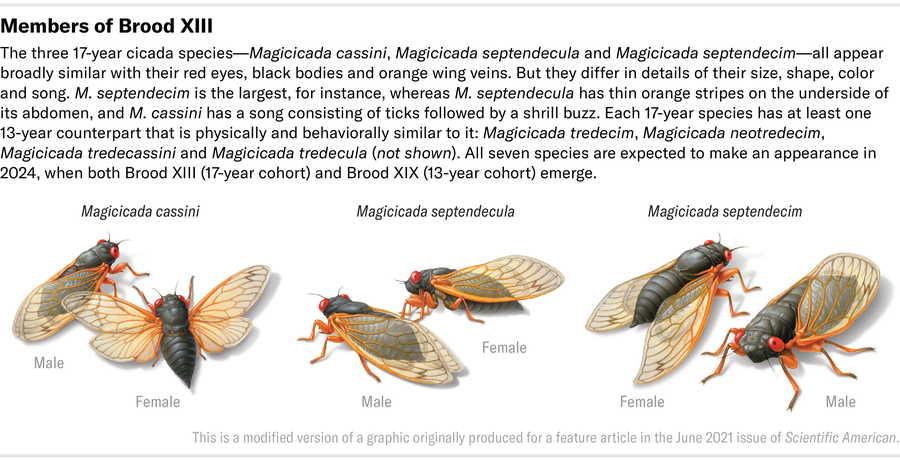

Cicadas can be eaten at three different life stages: nymph, teneral and adult. All three stages sport the distinctive red eyes that set periodical cicadas apart from the so-called annual cicadas that don’t synchronize their emergence. Cicadas come aboveground as brownish nymphs with stubby wings. After the insects complete their final molt, they spend a few days as ghost-white tenerals with full-size wings. The cicadas only become full adults when their final exoskeleton hardens and their body darkens.

Although it’s possible to collect nymphs by digging them out of the ground, Yoon says they’re cleaner if you wait for them to emerge on their own terms. He also recommends collecting adults earlier in the emergence. “The sooner you collect the adults, the more meat there’ll be on them,” he says.

Whatever the stage, Yoon says, collect the cicadas alive and then rinse the bugs, dry them and freeze them—which both euthanizes the insects and preserves them for future consumption. When you’re ready to cook—he doesn’t recommend eating them raw—running them under cool water will quickly defrost the insects. Some people prefer to remove the wings, but that isn’t necessary.

From there, options abound. “I’ve done everything from frying them with a lot of aromatics and adding them to stir-fries, adding them as a topping on top of guacamole or something,” Yoon says of the nymphs, which can also be blanched or fried in butter before they are covered with chocolate for a sweeter bite. His favorite technique for nymphs is to ferment them in kimchi. “All the kimchi juices kind of get absorbed into the cicada nymph, and it kind of pops and bursts in your mouth,” he says. “It’s really just quite magical to prepare and enjoy.”

Adult cicadas are also versatile, he says. “I’ve added the adults in pretty much any dish that I make,” Yoon says, noting examples such as fried rice, stir-fried noodles and pasta sauces. “The only limitation we have with cooking with cicadas is our own imagination.”