Experts say a pneumonia outbreak among children in Ohio and a cluster of pneumonia cases in China are unrelated, despite some social media posts and tabloid articles that have ambiguously linked the two.

The usual respiratory pathogens are making their rounds this cold and flu season, yet the specter of the pandemic has left many on alert for the next novel agent.

“I understand outbreaks in China can make people nervous, but this is not that,” says Paul Offit, an infectious disease physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Although another global illness may emerge in the future, the current pneumonia reports are “nothing to worry about,” he adds.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Many pathogens that circulate in the Northern Hemisphere’s winter and year-round—including flu, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and now COVID—are far from benign and can lead to pneumonia in some cases. But experts say there is no reason to panic or interpret the current uptick in illnesses as anything other than the typical circulation of respiratory viruses and bacteria.

These are “just everyday pathogens that normally increase during the winter having a somewhat early and very assertive increase at the present time,” says William Schaffner, an infectious disease physician and a professor at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. But people are not helpless against these germs, says Rama Thyagarajan, an infectious disease and internal medicine physician at the University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School. COVID, the flu and RSV all have vaccines that can reduce the risk of pneumonia, she says.

Schaffner agrees, calling these immunizations “the best present you can give in this holiday season to yourself and to your family and to your neighbors.”

Here’s what to know about the recent reports of pneumonia and the term “white lung pneumonia,” which has been used in some news coverage to describe the uptick in cases.

What clusters of pneumonia cases are being reported?

Warren County, Ohio’s public health department, which serves the northeastern suburbs of Cincinnati, reported a large uptick in the number of typical pneumonia cases in children, with 145 cases in those three to 14 years old recorded as of November 29. Massachusetts has also reported an increase in RSV and “walking pneumonia” among children.

Earlier in November China had reported an increase in respiratory disease cases. Chinese health officials attributed this uptick to the lift of COVID restrictions and the usual rise in known pathogens that can also make people vulnerable to pneumonia, including flu, COVID, RSV and infections caused by the common bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The World Health Organization is monitoring those cases, as well as an increase in pediatric respiratory disease cases in northern China.

Meanwhile multiple countries in Europe have also reported a rise in pediatric pneumonia cases, many of which are also caused by Mycoplasma bacteria.

None of these clusters, however, appear to be related to one another or caused by unfamiliar bugs. Initial reports on the increase in Warren County came from school nurses who said that a lot of students were calling in sick, according to Clint Koenig, a family physician and the medical director of Warren County Health District.

“We’re pretty confident that this is way above what we’ve seen this time last year,” he says. But Koenig adds that it’s hard to say how many more cases there are because data on children’s pneumonia cases are not routinely collected. Regardless, the causes of pneumonia are no different than those of past years: mostly RSV, adenovirus and Streptococcus or Mycoplasma infections.

What’s causing the current uptick in pneumonia cases, and how severe are they?

The growing pockets of pneumonia trace back to the usual increase in respiratory illnesses that occurs every winter, Schaffner says. Just as some flu seasons are more intense than others, the spread and severity of other winter diseases can also vary from year to year. Some upticks might be occurring as the usual seasonality of these pathogens continues to settle back into prepandemic patterns after it was disrupted by lockdowns, masking and social distancing, Schaffner says. But the biggest cause is likely that pathogens have more opportunity to spread in the winter.

“These viruses are taking advantage of us now that we are close together in birthday parties, schools, travel, religious services—whatever brings people together indoors,” Schaffner says. “And of course, we anticipate even more of that, given the holiday season. The New Year’s parties, all the travel associated with that and vacations are all wonderful environments that predispose to the spread of all of these respiratory infections, some of which will eventuate in pneumonia.”

What is the difference between pneumonia, “walking pneumonia” and “white lung syndrome”?

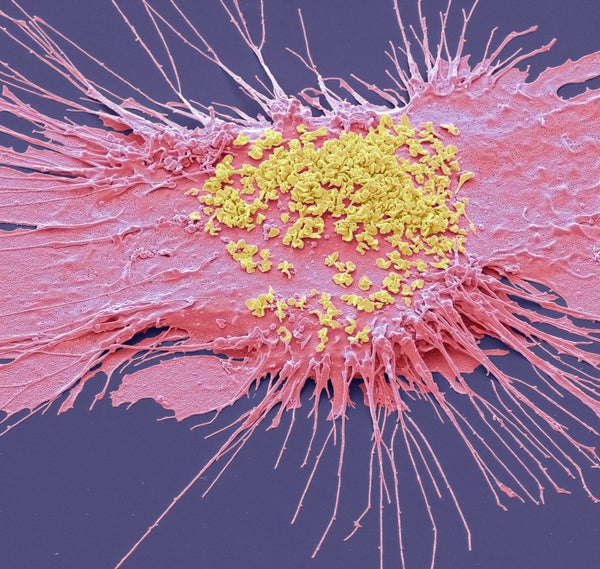

Pneumonia is an inflammation of the lungs that can be caused by a wide range of viruses, bacteria and fungi. Most respiratory infections involve the upper respiratory tract—the nose, throat and upper bronchial tubes, Schaffner says.

An infection develops into pneumonia when it reaches the lower respiratory tract and invades the lung tissue. This causes the lung’s white blood cells to trigger an inflammatory response. “If you get a lot of pneumonia, it will materially interfere with your ability to exchange gases. You can get short of breath, and you can have difficulty breathing,” Schaffner says.

Other symptoms include cough, fever, chest pain, fatigue and loss of appetite.

At least a dozen different pathogens can lead to pneumonia—no individual pathogen is responsible for even one in 10 cases. In fact, the pathogen behind any particular case of pneumonia is often never identified. Most pneumonia cases are triggered by a bacterium, but pneumonia is also a possible complication of respiratory viruses, such as COVID, influenza, RSV and even the common cold. These viruses can cause pneumonia by themselves or by making the body more vulnerable to secondary infections.

“Once somebody is infected with a virus, they’re more prone to get a bacterial infection on top of that” because the viral infection reduces their immune defenses, Thyagarajan explains. “The people that are affected are very young—infants and very young children—and very old and people with chronic illness.”

“Walking pneumonia” is a lay term often used to describe mild pneumonia cases, particularly those caused by Mycoplasma bacteria. It also has been called atypical pneumonia, Thyagarajan says, and can cause fevers, a dry cough and sometimes ear infections. According to Offit, “walking pneumonia” is usually not that severe. “Although we treat it with antibiotics, it usually is, for the most part, limited,” he says.

“White lung disease,” or “white lung syndrome,” is nothing but “a scary lay description, not used by medical professionals, of what we see on a routine chest x-ray,” Schaffner says. Healthy lungs full of air appear black in an x-ray because air looks dark in a normal reading. When inflammation and white blood cells fill the area, the lungs become opaque and more white on the reading, Offit explains. “It’s neither a scientific nor a medically acceptable term,” he adds.

How does pneumonia differ between children and adults?

Pneumonia symptoms are similar in children and adults, though young children may also experience nausea and vomiting, and older adults may have confusion. Beyond that, “different bugs are more apt to produce pneumonia in children than adults,” Schaffner says. “The older you get, if you have underlying illnesses, these respiratory viruses are more likely to result in pneumonia.”

Older adults tend to fare worse with pneumonia. Though pneumonia is the number-one cause of hospitalization in children in the U.S., older adults hospitalized with the disease have a greater risk of death than those hospitalized for any of the other top-10 reasons. That’s why it’s particularly important for older adults to get their RSV, flu and COVID vaccines, Thyagarajan says. “The populations who are at higher risk for complications, hospitalizations and dying from respiratory viruses and bacteria are the same populations who will benefit most from these vaccinations,” she says.

How is pneumonia treated?

Most viral pneumonia can only be treated with supportive care, such as providing oxygen; people with severe cases may require ventilators, heart-lung machines and other forms of mechanical ventilation, Offit says. Bacterial pneumonia is treated with antibiotics.

If you are otherwise healthy, there’s no need to contact a health care provider in the first several days of developing a respiratory infection, Thyagarajan says. But if you develop warning symptoms, such as confusion, shortness of breath or a fever that lasts more than three or four days, “it’s prudent to call your health care provider or seek emergency care,” she says.

Antivirals for flu and COVID, such as Paxlovid, can reduce the likelihood of developing pneumonia when taken early in the course of illness. Those in high-risk groups who develop respiratory symptoms, including those who have a chronic illness or are immunocompromised, should call their health care provider even when the symptoms seem mild, Schaffner says. That way they can get tested for flu and COVID to see if they potentially qualify for medications that reduce the severity of those diseases. Diagnosing an infection and treating it early are key to stopping it from turning into pneumonia.

How can you prevent pneumonia?

Though vaccination can’t prevent all cases of pneumonia, five vaccines recommended in the U.S. can substantially reduce risk of it. Two of these are already routinely recommended for children: the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV15 and PCV20) and the Haemophilus influenzae (Hib) vaccine. Pneumococcal vaccines are also recommended in adults aged 65 and older, as well as adults with certain medical conditions.

The COVID and seasonal flu vaccines, recommended for everyone aged six months and older, greatly reduce the risk of those diseases developing into pneumonia. Protection against RSV by the monoclonal antibody nirsevimab (Beyfortus) and the recently approved RSV vaccines can also reduce pneumonia risk in those eligible, including adults aged 60 and older, pregnant people, babies and some toddlers.

(Pneumonia develops in one out of five cases of pertussis, or whooping cough, so pertussis vaccination can also prevent pneumonia.)

The same behaviors recommended to prevent the spread of COVID, such as masking, staying home when sick and social distancing, will also reduce risk of other respiratory illnesses that can cause pneumonia.

“If you’re in a high-risk group—you’re older, you’re frail, you have underlying illnesses, you’re immune-compromised—you can get out your mask, and you can be more cautious when you travel or go to the supermarket or any indoor gathering of people,” Schaffner says.

Thyagarajan says she wears her mask at large gatherings in the winter season to protect herself and to protect others as well. That’s especially important if you are a caregiver for an older person or young baby, she adds.

Avoiding people who are coughing and showing other symptoms is obviously ideal, too, but it can be difficult to do, Schaffner adds. Stay home if you are sick—it’s ultimately one of the best ways to avoid spreading illness.