If you’ve ever driven a car, you’ve probably had the experience of parking on a hot, sunny day, running a quick errand or two and then returning to find your vehicle has become a stifling oven. That heat isn’t just uncomfortable; it can be deadly.

Since the late 1990s the U.S. has seen an average of 37 children die each year from heatstroke after being unattended in a car or other vehicle—a grim statistic that has remained stubbornly steady despite decades of efforts to raise awareness. The problem, experts say, stems from a lack of understanding of just how quickly a car can heat up and overwhelm a person and the difficulty of comprehending that even the most loving caregiver might be capable of leaving a child in a vehicle. Because news coverage tends to focus on more sensational stories that involve neglect, “the public perception is ‘that’s a bad parent; I’m not a bad parent,’” says Andrew Grundstein, who studies climate and health at the University of Georgia.

Scientific American dug into the science of why cars get so hot, why faults in our memory can lead anyone to forget even something as important as a child being in the back seat and what strategies can avert these deaths. “They’re so preventable,” Grundstein says. “They don’t have to happen.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A ‘National Problem’

Perhaps no one knows as much about the issue of pediatric vehicular heatstroke as Jan Null, an adjunct professor at San Jose State University, who maintains the most robust U.S. dataset on such deaths at NoHeatStroke.org. He pulls the numbers primarily from news reports because there is no official centralized, comprehensive record; coroners don’t always note that such deaths occurred in a car or involved heat.

Null fell into what he calls his “sad niche” when he received a call from a reporter in July 2001 after a boy in the San Francisco area had died in a hot car. The reporter wanted an expert’s take on what temperatures might have been involved. Null couldn’t find any good studies on that question and quickly realized that little solid information was available. So he took it upon himself to start investigating and gathering data.

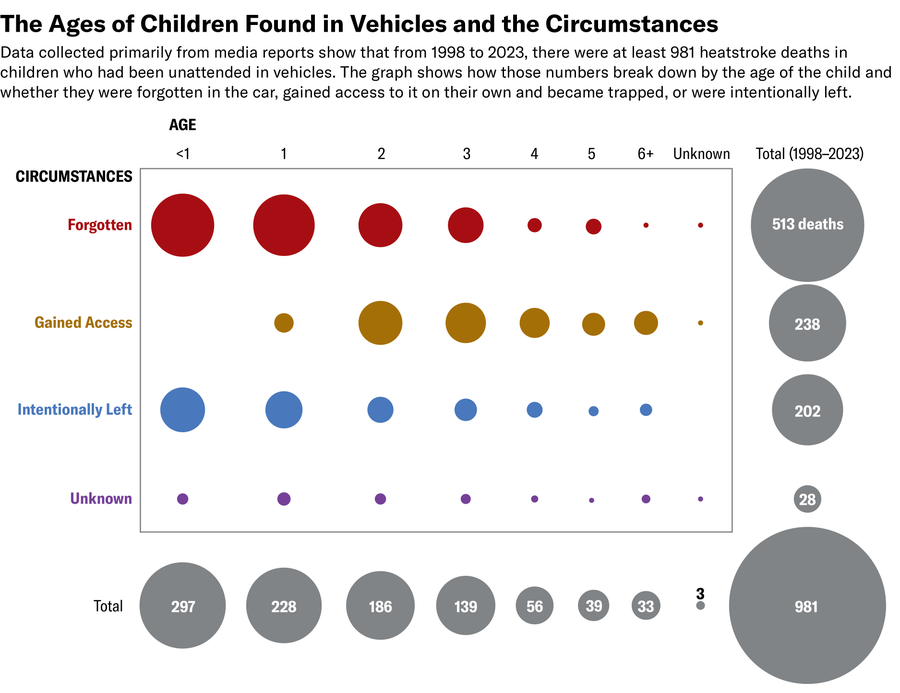

More than 20 years later Null continuously updates his database, which includes the age and gender of each child, where the death occurred and other pertinent information. The vast majority of deaths involve very young children: about 88 percent are three years old or younger, and nearly one third are less than a year old.

Zane Wolf; Source: NoHeatstroke.org

Such heat-related fatalities have happened in every month of the year, though they tend to peak in summer. They happen more often across the southern portion of the country because of the longer hot season and more intense heat. But they have happened almost everywhere—only two states, Alaska and New Hampshire, has not had a recorded death of a child in a hot car between 1998 and the present (and New Hampshire had one in 1997). “There’s really not a safe place for this. It’s really a national problem,” says Grundstein, who has worked with Null. He also notes that the problem goes far beyond the U.S., citing studies in Europe and South America as well.

How Hot Can It Get in a Car?

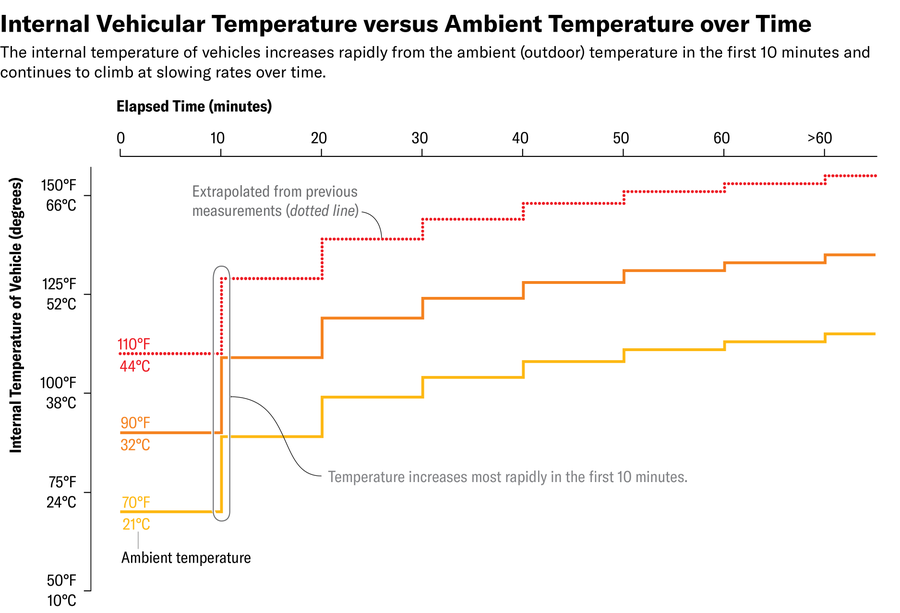

Until Null started his work, there were no comprehensive measures of how hot a car’s interior could get in different outside temperatures or of how quickly this heat could become dangerous. In preliminary anecdotal work Null did in his own car, and later in controlled studies, he found “very rapid rates of rise”—around 19 degrees Fahrenheit (10.6 degrees Celsius) in the first 10 minutes—regardless of the starting outdoor temperature or type of vehicle.

The inside temperature continues to rise at a slowing rate, reaching extremely high temperatures. If the outside air is 90 degrees F (32 degrees C), the temperature in a car will reach 133 degrees F (56 degrees C) in roughly an hour. Even with a mild outdoor temperature of 70 degrees F (21 degrees C), a car’s interior can reach 113 degrees F (45 degrees C) in that time.

Zane Wolf; Source: NoHeatstroke.org

That’s because “cars operate like a greenhouse,” Grundstein says. The relatively short wavelengths of sunlight are able to stream through the windows of the car, heating up the air and surfaces inside. Those surfaces then radiate longer wavelengths of infrared energy—or heat—that do not penetrate back out of the windows but very efficiently heat up the inside air.

Why Children Are So Susceptible to Hot Cars

Such heat is dangerous for any person in a car, but children, particularly very young ones, are so susceptible in part because “they’re strapped into a car seat; they’re not able to remove clothing; they’re not able to get out of the car,” Grundstein says. “They’re literally trapped in there.”

The longer the child is in the car, the more the heat radiating from its surfaces is driving up the child’s core body temperature. “The human body is just gaining heat internally” in this situation, says Susan Yeargin, who studies heat illness at the University of South Carolina.

A normal human body temperature is around 98 degrees F (36.6 degrees C). It becomes dangerous when the core temperature rises to around 104 to 105 degrees F (about 40 degrees C). Potentially fatal heatstroke—often marked by hot, dry skin, dizziness and vomiting—typically occurs around 107 to 108 degrees F (about 42 degrees C), Yeargin says.

Children primarily lose heat by simply radiating it from their skin to the air. Perspiration—the main way adults cool themselves—doesn’t take over as the body’s primary cooling method until puberty, so younger children cannot sweat away heat as well as adults do. But in a hot car, “the heat gain in the environment is just so much that the child or the person can’t dissipate it with the sweating mechanism alone,” Yeargin says. Eventually the body is only gaining heat, and that heat can quickly damage internal organs.

Why Parents Can Forget Their Children in a Car

The cases of children who die from heatstroke in a vehicle fall primarily into three categories: about 20 percent are knowingly left; one quarter gain access to a car and become trapped; and more than half are forgotten. Of the latter, half are left in cars because someone forgot to drop them off for childcare—typically a parent or other caregiver who does not usually drive the child there. “No one thinks they’re ever going to do that,” Grundstein says, “but it happens to anyone.”

One reason it can happen to an otherwise attentive caregiver is that “as magnificent as our brain is, our brain is flawed,” says David Diamond, a neuroscientist at the University of South Florida, who has studied this issue for more than 20 years. Our brain, he explains, has two independent memory systems: One is our conscious memory, handled by the hippocampus. “This is where we actually keep things on our mind,” Diamond explains. The other is a “very primitive but powerful brain memory system” controlled by the basal ganglia, where actions we take repeatedly—brushing teeth, locking a door—get ingrained as habit. That latter memory system dominates when we’re driving, Diamond says.

“No one thinks they’re ever going to do that, but it happens to anyone.” —Andrew Grundstein, University of Georgia

He offers a typical example: Your significant other asks you to drop by a store to pick up milk on the way home from work, a stop you don’t normally make. You agree, think about how you need to alter your route and set off. But as you start off on a route you’ve driven hundreds of times before, the basal ganglia makes you “go into autopilot mode,” Diamond says, “and you drive right past the store.”

A similar thing can happen when a caregiver is driving a child to day care on their way to work, particularly if they are not the one who normally drops off the child. Their brain goes on autopilot, and they end up driving their normal route to their job or train station or wherever their end destination is. “The habit takes over and keeps them on their routine,” Diamond says. And if the child is out of view or asleep, the parent may not notice them. “No matter how precious the memory is,” it can fall through the cracks, he says. “It’s easy to judge; it’s difficult to understand,” Diamond adds. “It’s part of being human.”

Then “what the brain seems to do is it leaves a false memory” that the child is at day care or wherever the caregiver planned to bring them, Diamond says. “[The caregiver has] absolute certainty that the child is wherever the child belongs”—even thinking at the end of the day, “Oh, I need to go to day care to pick up my child.”

How Do We Prevent Heatstroke in Cars?

There are ways to help prevent children from being forgotten or otherwise becoming trapped in cars. But because it happens for a variety of reasons, “you need different strategies for different circumstances,” Grundstein says.

Cars should always be kept locked so that a child cannot open a door, climb in and subsequently become stuck because of child safety locks or other reasons, experts say. Children should be taught that a car is not a safe place to play. And if a child has gone missing, the first place to check is a pool, if one is nearby, and then the car, Null says, because they are the two places a child can most quickly come to harm.

Zane Wolf; Source: NoHeatstroke.org

When it comes to children intentionally left in a car—often with no harmful intent—awareness campaigns can help. Twenty-one states have also passed laws making it illegal to leave a child in a car, though many have exceptions, and it is unclear whether those have had any effect on the number of cases. Twenty-four states have “Good Samaritan” laws that protect anyone who sees a child in a car and takes action to help them, such as breaking a window. Null says if you see a child alone in a car, your first action should be to call 911, particularly if there is any sign of distress.

To help prevent children from being forgotten, new car models are now required to include technology that will remind the driver to check the back seat. But it will take some time for this technology to spread through the U.S. car fleet.

In the meantime—given that 25 percent of cases of a child dying in a hot car occur when they are forgotten on the way to a childcare provider—Null would like to see childcare provider contracts include a provision that the provider must call the parent if the child has not arrived by a certain time. Because drop-off usually occurs earlier in the morning, Null says, “it’s gotten warm, but it’s not gotten that hot early in the day.” So the chances are greater that the child can be rescued before they come to serious harm.

There are also “look before you lock” campaigns, many of which include low-tech suggestions for reminding a caregiver that their child is in the back seat. This could include putting a Post-it note on the steering wheel or keeping a work bag or purse in the back seat. Diamond particularly likes the method of keeping a stuffed animal or some other object in the car seat when it’s not in use and then routinely moving that object to the front passenger seat or, if small enough, attaching it to the steering wheel when the child is put into the car seat. But “you have to do it every time you have your child” for the reminder to work, Diamond says.

The thorniest problem with those approaches is that they require people to confront and accept the thought that they could forget their child. “Probably the biggest roadblock is that people say, ‘It would never happen to me,’” Null says.

Because of that and the fact that “people are fallible,” he doesn’t think such deaths will ever reach zero. But he and others do think we can bring the numbers down. “Awareness and education are huge,” he says, adding that he personally will keep tracking the data and providing his database for free in order to advocate for safety. “I would love to get a different passion project,” he says. In the meantime, he’ll “keep slugging away.”

Editor’s Note (9/26/24): This article was edited after posting to correct Jan Null’s current position at San Jose State University and the context of the call he received in July 2001.