The stereotype of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is someone, often a young boy, who can’t focus and can’t sit still. And there are certainly people who fit that description. But the condition often presents very differently—for instance, some people with ADHD have a tendency to sit for hours and focus on a project to the point that they forget to eat and ignore the world around them. In that case, ADHD can be more about an overabundance of focus rather than a deficit. And many with ADHD—especially girls, who tend to go undiagnosed—aren’t hyperactive at all.

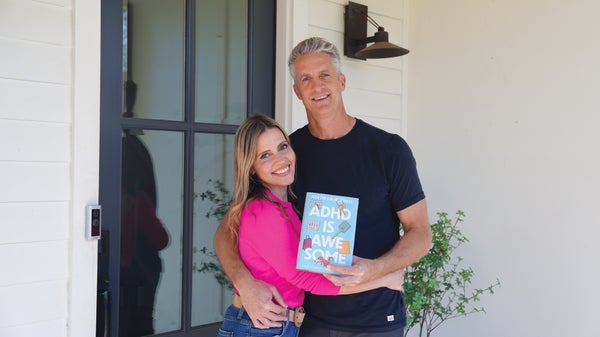

A new book, ADHD Is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHD (Harper Horizon, 2024), by Penn and Kim Holderness, aims to update the conversation about ADHD and point out the benefits along with the challenges. “ADHD is a superpower,” says Penn Holderness, who sees many benefits of his own ADHD diagnosis, including a special ability to concentrate on things he’s interested in, solve problems and be creative. He and his wife, Kim Holderness, have gained fame for creating popular online videos about family life, many of which showcase aspects of ADHD. Penn struggles with remembering daily tasks—and sometimes leaves his keys in the refrigerator.

But he and Kim also credit his ADHD superfocus for their 2022 win in the CBS reality competition The Amazing Race, which required them to solve puzzles, assemble musical instruments and complete detailed memory tests, among other challenges, during a trip around the world.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Scientific American spoke to the Holdernesses about ADHD perception versus reality, ways to support loved ones with the condition and how ADHD helped them win $1 million.

[An edited transcript of the conversation follows.]

What do you hope people get out of the book?

PENN HOLDERNESS: I hope people get that they’re not alone and they’re not broken. There’s nothing inherently wrong with them. If they have ADHD, they actually have a pretty fantastic brain—a very unique brain—and the world would be very boring without all of us.

They didn’t have this book when I was a kid. I can’t go back in time and give this book to myself, the kid who struggled and wondered why he was so weird. We’ve gone on a journey to discover what ADHD really is because even those who have it don’t always really understand it unless they take a deep dive into it. Once you realize what it is, you can quickly discover that there are some wonderful traits to this, as long as you put systems in place to manage the rough stuff.

Tell me more about this superfocused state associated with ADHD that you sometimes find yourself in.

PENN HOLDERNESS: The extra focus, which is also known as hyperfocus, is the ability to really hammer down and knock out of the park one specific thing. [YouTuber and ADHD advocate] Jessica McCabe wrote another book about ADHD, and she says that the three things that ADHDers do well on are things that are difficult, new and of personal interest. So if there’s something that is of personal interest to you and that is new and challenging, you can be exceptional at that.

KIM HOLDERNESS: From an outsider’s perspective, Penn will be editing something, and editing videos and creating music is a personal interest to him. He’ll be here for eight hours, and he will not have eaten. He will not have gone to the bathroom. It’s like this flow state that is pretty amazing to witness. His brain can just lock in to a challenge.

PENN HOLDERNESS: People have said to me, “I think COVID gave me ADHD.” I understand that sentiment because there were a lot of people getting hooked on screen time and a lot of new sorts of distractions, such as Zoom meetings, that are rough on people with ADHD. But I think it’s important that people know that it’s not something that’s acquired. It is the way that your brain was at birth. Now, it’s very possible that during COVID people realized that they had ADHD, but it’s the way that you are wired, not the way that you are behaving.

KIM HOLDERNESS: And it’s not the way you were raised. Too much screen time is not going to give you ADHD. And women and members of minority groups are historically underdiagnosed. I think so many women were white-knuckling it, and then maybe in the pandemic something happened that made them aware enough to get tested.

Kim, what tips do you have for supporting someone with ADHD if you’re their spouse, parent, friend or family member?

KIM HOLDERNESS: I have had to do a lot of work on this because I am a perfectionist. I think everything is very black and white, and I love rules. You turn on the stove, so you would obviously turn it off; your keys go on the hook; you put the dishes in the dishwasher. That makes sense to me. And it took me a while to understand Penn wasn’t forgetting these things on purpose. But in his brain, it didn’t enter his working memory that he had turned the stove on because he was doing five things that morning. He was getting homework in the backpacks, he was making himself coffee, he was feeding the dog, and he had turned the stove on, and that step didn’t enter his memory. So he left it on and left the house. If I jump down his throat and say, “You nearly burned the house down!” he already knows that, and he’s already feeling great shame. So the thing is, connect, don’t correct. I try to just offer sympathy. I’m not saying, “Oh, it’s just your ADHD. Don’t worry about it.” We always say, “ADHD is an explanation; it’s not an excuse.” But I am saying, “Wow, that really sucks. I am so sorry that happened. That could have been scary.” It sounds so simple, but it was so hard for me to really accept.

Tell me more about how you think ADHD helped you win The Amazing Race and its $1-million prize.

PENN HOLDERNESS: The Amazing Race created this kind of perfect tunnel-vision spot for somebody like me because I’m interested in $1 million, and they purposefully make it as difficult as possible to try to trip you up all the time, and it is absolutely new—going out and seeing the world and going to all these new places and doing all these new challenges. So my brain was able to slip into hyperfocus very easily. What also helped was that I had one job. There weren’t a lot of things competing for my attention, with the exception of beautiful scenery everywhere, which I did have a little trouble with.

KIM HOLDERNESS: He really is the reason we won in so many challenges because he was the one who could, like, put a mule’s harness on or do these other weird tasks. But with my brain, I was seeing the other teams, I was seeing the camerapeople, I was seeing the mountains we were in—I was seeing everything. And he could narrow it down in a way that was pretty cool to see.

Have you found that most doctors and scientists are on the same page with this idea that ADHD doesn’t necessarily mean something’s wrong with you and that it actually has benefits?

PENN HOLDERNESS: I think science has a pretty good bead on how it works. There are lots of great people who have learned and explained and discovered these things. But science doesn’t necessarily know how to explain it to people.

KIM HOLDERNESS: Science needs a better marketing team. And that’s what we’re trying to do. They say, “Write the book you need,” right? And our family personally needed this book. As we were doing interviews for this book and reading all the research on it, [we saw that] there are so many brilliant people out there doing the work. I think they needed bigger microphones, and they needed a better way of explaining it to the rest of us. I think that the simpler we can put the language around it, it’ll just help the rest of us to catch up.