Water levels are dropping in reservoirs. Multiple wildfires have ignited tinder-dry brush, exposing people across the region to harmful air pollution levels. It has barely rained for weeks.

This time we’re not talking about the frequently drought-plagued western U.S. but rather the typically wetter eastern portion of the country—where an unusually severe drought has triggered water restrictions, damaged crops and fed as many fires in six weeks as New Jersey typically sees in six months. Some of the effects resemble those of dry periods out West, but drought in the East is a bit of a different beast.

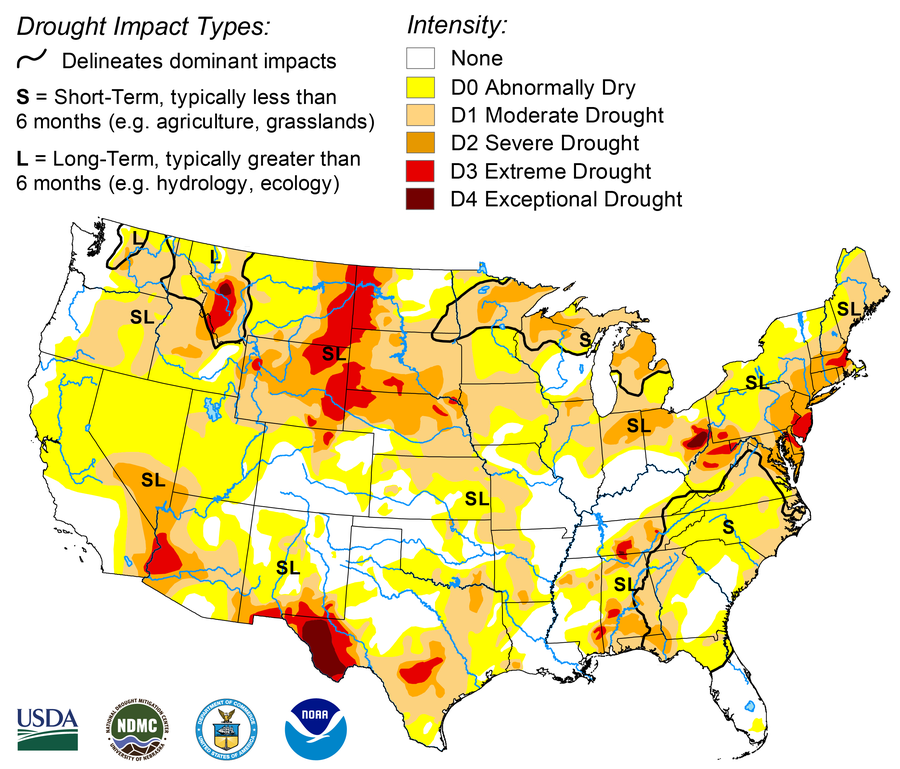

The two halves of the country have very different climates. Much of the West has distinct wet and dry seasons: rain and snow fall from late autumn through early spring, and that’s mostly it for the year. Snow on the high western mountain peaks gradually melts during spring and summer, keeping streams topped up and vegetation sufficiently watered when all goes well. But when winter precipitation is paltry or a hot spring and summer cause rapid snowmelt, there is less to keep reservoirs filled. Western states manage these resources to help gird against a dry year, but repeated years of failed rains and hot weather can usher in disastrous drought. This happened in California a decade ago, when hot weather officially pushed more than half the state into “exceptional” drought status—the highest category used by the U.S. Drought Monitor.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Much of the East Coast, on the other hand, can—and usually does—see precipitation every month of the year. Dry periods there “tend to be shorter-lived and not these same major disasters as in western North America,” says Benjamin Cook, a climate scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, who studies drought.

The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC.

But when a few weeks go by between rainstorms, drought can develop very quickly. This has particularly been the case this fall in the Northeast. After an extremely wet winter and spring, many areas there saw six weeks with very little or no rain and unusually warm temperatures. And hotter temperatures increase evaporation, drying out the ground and plants even faster. “What’s wild is how far we’ve fallen down” in terms of water in the Northeast, says David Boutt, a hydrologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “All these lakes and streams are feet lower than they’re supposed to be.”

Wells are running dry in Connecticut. Officials in Philadelphia are closely monitoring the Delaware River’s “salt front”—where its fresh river water meets the salty water of the ocean—in case the ocean water pushes farther up the lowered river and threatens drinking water supplies. New York City has declared its first drought warning in 22 years, asking residents to take various steps to voluntarily cut back on water use. “It’s just not something that the Northeast typically deals with, so it’s shocking to read about,” says Denise Gutzmer, a drought impact specialist at the National Drought Mitigation Center.

It could be worse. The drought of record in southern New England hit in the 1960s after years of below-normal rainfall. If those same conditions occurred now, with all the population and infrastructure growth since then, “we would be in really bad shape,” Boutt says. “Most places would be out of water or barely hanging on.”

The East Coast’s current dry conditions have also made fall wildfires much worse than usual; they are igniting more readily, and they are burning hotter and longer. “We’re used to having some kind of reliable rain, and that helps put our fires out,” says Michael Gallagher, a U.S. Forest Service research ecologist, who studies wildfires. This year, though, “the fires keep popping up in more and more atypical places,” including Prospect Park in the heart of Brooklyn, N.Y., and small green spaces in Manhattan.

One small thing that is keeping the drought from being worse is that it is happening in the fall, when both people and plants need less water and there is generally less evaporation than in the heat of summer. But the seasonal timing is also contributing to other wildfire-worsening factors: for example, deciduous trees are dropping leaves, adding more potential fuel for any spark.

A few storms have brought a small amount of rain and snow to the region last week and this week, tamping down on fires and reducing the risk of further blazes. But they won’t end the drought; it will still take time for those rains to add up to enough to erase the current deficit. “We’re not just one rainstorm away from everything being better again,” Gallagher says. Boutt concurs, saying, “The soils are just so dry” that it’s probably going to take precipitation amounts of 10 inches, distributed over the next few months, to get water levels back up to normal.

Exactly what the weather will bring for the rest of the fall and winter is uncertain. Reliable weather forecasts only extend about seven days into the future, and seasonal forecasts just give the relative odds of what the weather over the next few months will be. For the Northeast, the odds currently favor warmer-than-normal weather— but roughly equal chances of wetter or drier conditions.

Looking ahead even further, as the climate continues to change with rising temperatures, the work Boutt and others have done suggests that vacillations between wet and dry periods in the Northeast are occurring more frequently, on the order of every two to four years.

For the rest of this year, the wildfire risk should at least diminish a little as the days get shorter and nights get colder. “It just doesn’t burn as well when it’s really cold out,” Gallagher says. This is particularly so when there is an overnight frost because it takes time for that frost’s moisture to evaporate when the sun rises. Gallagher does caution, though, that major Northeast wildfires have occurred in every season. If a dry, windy weather pattern takes hold again, fire activity could resume.

And even if there is some rain and snow in the next few months and fire danger remains low, there is a certain amount of “memory’ in the water table, streams, rivers and lakes—it takes time for them to recover, Boutt says. “We’re going to be feeling this into spring and summer,” he adds.