Tiny creatures are gnawing away at plastic we humans are pouring into the environment, making the pollution less visible but potentially more problematic than ever, according to new research.

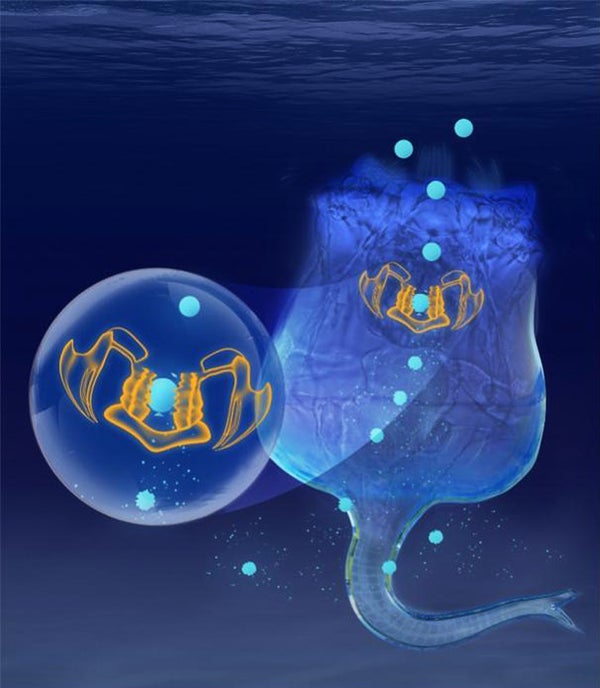

In that work, published on November 9 in Nature Nanotechnology, scientists fed small pieces of fluorescent plastic to plankton called rotifers and watched to see what happened. Their observations and analysis suggest that in just a single day, one of these tiny animals in a plastic-rich environment can produce more than 300,000 particles of nanoplastic that are smaller than one micron across—a fraction of the size of a human red blood cell.

Nanoplastic is a major concern within the larger problem of microplastics, which cover a wide range of sizes, from one micron to five millimeters. Nanoplastics’ even smaller size could make them particularly harmful to humans and the environment because they can more readily get into the bloodstream and deep into the lungs. They can also be ingested by small animals and become concentrated up the food chain. The new study—which complements a growing body of research showing that plastic pollution extends from the deepest ocean trenches into the atmosphere—sheds light on how astoundingly quickly plastic can proliferate.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“We know that microplastics eventually become nanoplastics, but you don’t think it’s going to happen that fast,” says Jacqueline Padilla-Gamiño, a marine biologist at the University of Washington, who was not involved in the new research. Other natural forces, most notably sunlight, also break plastic into progressively smaller pieces but act more slowly.

The scientists behind the new research were inspired by a 2018 study that showed that Antarctic krill could break microplastics into nanoplastics. Those animals live in extremely cold—and less polluted—environments, however. The researchers behind the new work wanted to understand whether the same phenomenon also played out in animals that lived in warmer, more plastic-filled waters, says study co-author Baoshan Xing, an environmental and soil scientist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

From there, rotifers were an obvious choice because they are common and equipped with what scientists call trophi—specialized grinders to process their diet of algae and other tiny bites. “Rotifers have this special chewing apparatus, like teeth,” Xing says.

Xing and his colleagues found that multiple rotifer species do indeed break down microplastic. Some experiments have suggested certain bacteria and enzymes can digest plastic by breaking apart the very molecules that it is made of, chemically changing them into benign compounds and reducing the amount of plastic in the environment. But the researchers found a different, less optimistic outcome: the rotifers merely fragmented the plastic by making scratch marks on the plastic bits and creating ever smaller pieces. The scientists tested different types of plastic, as well as plastic weakened by exposure to light, and all were vulnerable to the rotifers’ trophi.

Xing says it’s unlikely that rotifers are alone in their staggering ability to tear apart microplastic. “We think any organisms with that type of chewing apparatus likely will have a similar process,” he says. He and his colleagues want to conduct comparable investigations using more species, particularly animals that live in soil rather than water, to understand how the phenomenon may be playing out in a wider variety of ecosystems.

The new research, Padilla-Gamiño says, is an important step toward understanding what happens to plastic over its long lifetime of up to hundreds of years in the environment. “We have made huge advances into [understanding] how much plastic there is, but there’s still a lot of controversy about the different pathways that plastics take,” she says. “I think this is a very cool study highlighting one of these pathways.”

And it’s also a reminder not to overlook the tiny, strange forms of life that we share our planet with. “It’s amazing how these little creatures have such tremendous power,” Padilla-Gamiño says.