With the vinyl revival upon us, artists are enhancing new albums with old tricks. A handful of albums, including releases from Dua Lipa, Gorillaz, Olivia Rodrigo and Glass Animals, plus a new release of the soundtrack to Disney’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, are available on a special type of record called a zoetrope vinyl—a modern spin on 19th-century animation technology. When viewed correctly, illustrations on the record combine into a smooth, animated loop. But as some TikTok users have pointed out, these animations cannot be seen with the naked eye in normal lighting; all you get is a blur. And that has to do with our psychology and physiology.

The zoetrope was among several kinds of animation gadgets invented in the 1700s and 1800s, before the first films were made. These hand-rotated devices, which were either circular or cylindrical, included the thaumatrope (a two-sided disk that spins like a coin), praxinoscope (an animation reel viewed via angled mirrors) and phenakistoscope (a spinning animation disk with slits that are viewed in a mirror). The zoetrope was the most popular, and this word is now widely used for all such systems, even those involving three-dimensional sculptures, says Christine Banna, an assistant professor of film and animation at the Rochester Institute of Technology. “It’s become an eponym for any physical animation device today, like how an iPod is [used to refer to] all MP3 players or Xerox is all copiers,” she explains. Both modern and vintage zoetropes use the same mind tricks to create the illusion of movement.

The afterimage of any one scene lasts in the human visual system for fractions of a second, Banna says. Because the image remains in the brain and eye after you stop seeing it—an effect called persistence of vision—if another image appears in that time frame, the two pictures seem to flow into each other. The brain then fills in the gaps between still images viewed in rapid succession and perceives this as movement, an illusion that early-20th-century psychologists named the phi phenomenon. “The persistence of vision and the phi phenomenon are the physiological and psychological reasons why animation works,” Banna says. “Our brains, simply put, want order in the images” that persist.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Movement illusions like these require two features: an observer must see at least six still images per second, and—importantly—there must also be a brief interruption between each image. “If we’re constantly feeding more images to the retina, the afterimages layer on top of each other,” Banna says. “If we don’t have that interruption, it would just be one continuous blur.” (This is why we need the aid of a smartphone to appreciate the new vinyl albums.)

Old-fashioned zoetropes had drawings on the inside of the cylinder of a barrel that were observed through tiny slits cut into the barrel above each picture. When viewed from the side, the spinning barrel’s surface periodically blocked the drawings. Thanks to those interruptions, an observer peering through the moving slits would perceive animation. (Modern equivalents can use strobe lights, angled mirrors or shutters.) That’s why the zoetrope vinyl records need to be viewed through a camera or phone app with adjustable shutter speeds—30 frames per second is typically ideal—or with a strobe light pulsing on the vinyl at a frequency of around 30 hertz. But you can make a less complex zoetrope with common materials found around the house.

How to Make Your Own Zoetrope

You’ll need scissors, a strip of paper, a pencil, chopstick or wooden skewer, tape, a pen or marker and a measuring tape. You’ll also need something with a circular base. You can use heavy paper, cardboard, disposable plates or bowls, or even an old CD.

Make the base

Measure the circumference of the object with a circular base to determine how long your animation strip should be. (It needs to be exactly long enough to wrap around the circular base to form a cylinder.)

Sketch out your animation loop

To plan your animation sequence, use your pen or marker to divide the strip of paper into same-sized frames. The sequence should be drawn on the bottom half of the strip. Leave the top half of the strip blank for the viewing slits. If you’re animating a character, sketch out the main poses every few frames, leaving some frames to fill in transitional movements. A smaller distance between each pose translates to slower, smoother animated movement. A larger distance creates more explosive action. If you don’t want to draw your own animations, there are free online templates you can print and cut out.

Cut out the viewing slits

To make your animation viewable, cut notches or thin vertical slits between each frame in the animation strip from the top to about halfway down. Each slit’s width should be about a third or a fourth of the distance between the frames. “If I have a quarter-inch slit, I would need roughly an inch between the frames,” Banna says. “We need that as a shutter for our eyes. It helps create that strobing with analog material.” (Based on experience, we suggest going with a thinner slit for a better animation illusion.)

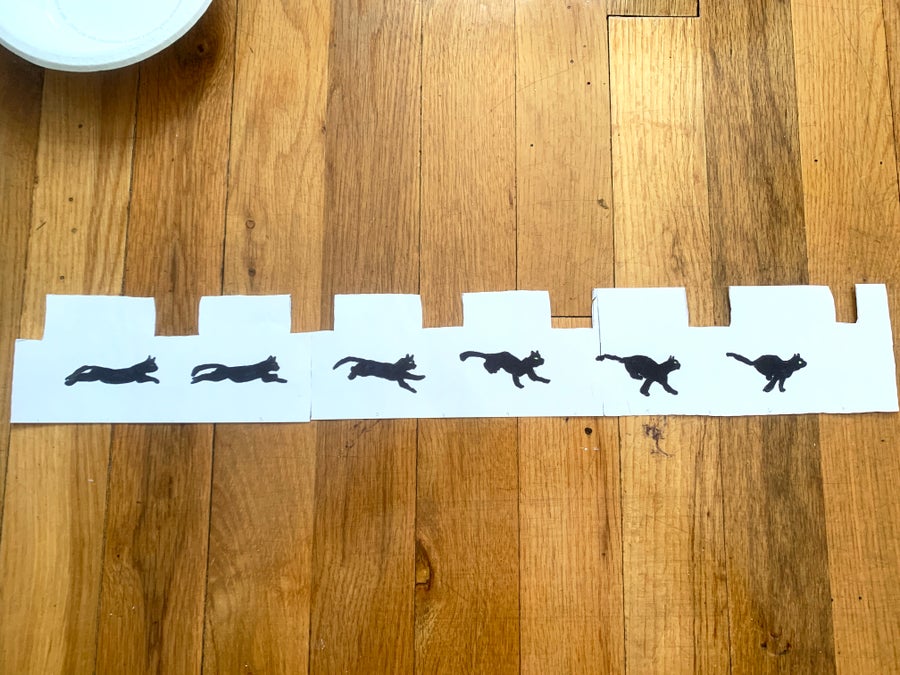

An animation sequence for a homemade zoetrope, with viewing slits cut between the frames.

Charlotte Hu

Turn the zoetrope

Tape the ends of the strip together so it forms a cylinder with the drawings facing inward, and then secure it onto the circular base.

Poke a pencil, chopstick or wooden skewer vertically into the center of the circular base from below. Make sure that the skewer stays firmly in place while you spin the zoetrope between your hands.

As you spin the device, watch the animation loop by looking through the slits. You can play around with how fast you spin it to get the best result.

Charlotte Hu

You can use similar methods to make a zoetrope with any cylindrical object—including a pumpkin (although you will probably need a turntable to spin one of those)! You can also use the same principles to make a phenakistoscope, which uses a similar physical animation technique and can be made with a disk and mirror instead of a cylinder.