Well, we always knew the alien-megastructure idea was a long shot.

E.T. has nothing to do with the bizarre dimming events of the mysterious object known as Tabby's star, a new study reports.

"Dust is most likely the reason why the star's light appears to dim and brighten," study leader Tabetha Boyajian, an astronomer at Louisiana State University, said in a statement. "The new data shows that different colors of light are being blocked at different intensities. Therefore, whatever is passing between us and the star is not opaque, as would be expected from a planet or alien megastructure." [13 Ways to Hunt Intelligent Aliens]

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

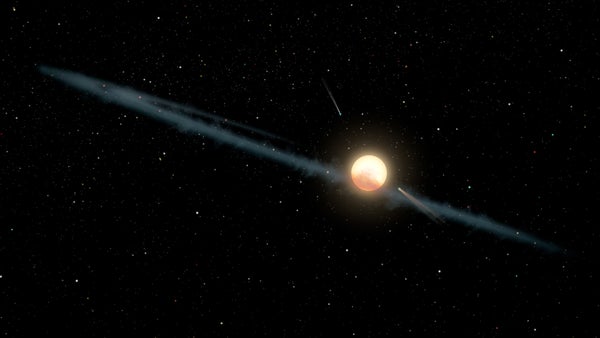

Tabby's star, more formally known as KIC 8462852, lies about 1,500 light-years from Earth and is a bit bigger and hotter than the sun. The star has been in the news a lot since 2015, when a team led by Boyajian (hence the star's nickname) reported that it had dimmed dramatically over the previous five years or so, once by a whopping 22 percent.

Further observations added to the intrigue. For example, a different research group found that Tabby's star had also dropped in brightness overall by about 20 percent from 1890 to 1989.

For the past two-plus years, astronomers have been trying to figure out what, exactly, is going on with Tabby's star. A number of potential explanations have been floated, from orbiting comet fragments, to a huge dust cloud between Earth and KIC 8462852, to energy-collecting structures built by an advanced alien civilization.

Researchers always stressed that this last possibility was quite remote. And now it looks like we can cross it off entirely.

For the new study, Boyajian and her team observed KIC 8462852 from March 2016 to December 2017, using multiple ground-based telescopes run by the Las Cumbres Observatory. They spotted and analyzed four separate dimming events, which occurred in the summer of 2017.

The new results are consistent with those of another research group, which late last year concluded that Tabby's star is likely orbited by a cloud of dust that completes one lap every 700 Earth days.

Boyajian and her team funded the new observations via a Kickstarter campaign, which raised more than $107,000. That's appropriate, because citizen scientists helped Boyajian recognize the weirdness of Tabby's star in the first place. Her 2015 paper was a collaboration with volunteers from the online group Planet Hunters, who sift through data gathered by NASA's Kepler space telescope, looking for alien worlds. (Kepler spots the tiny dimming events caused when orbiting planets cross their star's face from the spacecraft's perspective. KIC 8462852's massive brightness dips stood out in the Kepler data set as something very different.)

"I am so appreciative of all of the people who have contributed to this in the past year—the citizen scientists and professional astronomers," Boyajian said. "It's quite humbling to have all of these people contributing in various ways to help figure it out."

There is still work to do, however: Dust may be the leading explanation for KIC 8462852's odd behavior, but it's not the only possibility.

"This latest research rules out alien megastructures, but it raises the probability of other phenomena being behind the dimming," study co-author Jason Wright, an astronomer at Pennsylvania State University, said in the same statement.

"There are models involving circumstellar material—like exocomets, which were Boyajian's team's original hypothesis—which seem to be consistent with the data we have," Wright said. But, he added, "some astronomers favor the idea that nothing is blocking the star—that it just gets dimmer on its own—and this also is consistent with this summer's data.”

The new study was published online today (Jan. 3) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

EDITOR'S RECOMMENDATIONS

Copyright 2017 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.