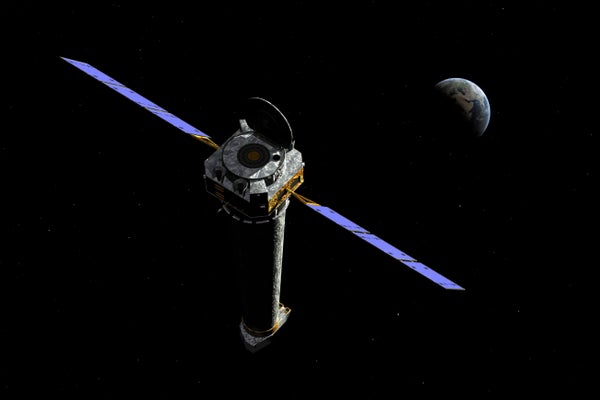

The Chandra X-ray Observatory is the darling of high-energy astrophysics. Famed for providing unequaled x-ray views of voracious supermassive black holes, exploding massive stars and even dark matter-infused collisions between galaxy clusters, the spacecraft probes the biggest mysteries in astrophysics.

But 25 years after seeing its first light, Chandra’s future is up in the air.

In March NASA slashed Chandra’s budget from $68 million in 2024 to $41 million in 2025 and $26 million a year later. According to the Chandra X-ray Center, which operates the telescope, this only allows for mission closeout. In the months since, a series of events—including an intense publicity campaign and a show of congressional support—has kept Chandra funded through September 2025. But for this year’s Senior Review, which evaluates NASA’s missions, the Chandra X-ray Center has been told to stay within the proposed budget numbers—that is, to plan how the spacecraft will shut down.

This is a mistake. Chandra should remain operational until it encounters a critical failure or is replaced by a comparable mission. Chandra is the only high angular resolution x-ray telescope in space, and there is no mission with similar capabilities scheduled to replace it until 2032 at the earliest.

One could ask: What new discoveries can Chandra make that it hasn’t made over the past 25 years? And that’s a good question. But our observational capabilities have changed greatly since Chandra was launched, and therefore so has its potential for making discoveries that require multiple telescopes. We have only recently reached the era of multiwavelength, multimessenger astrophysics, allowing simultaneous views of stars and galaxies in everything from the radio spectrum to gamma rays, neutrinos and gravitational waves. Much of that critical synergy will be lost and squandered if we give up on the high-resolution x-ray coverage.

In a sense, Chandra was ahead of its time. Some of the discoveries it will be remembered for, such as the detection of sound waves from supermassive black holes, are Chandra-only science. But its most significant recent results come from the combination of its keen x-ray vision with new instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope or the Event Horizon Telescope.

The Chandra X-ray Observatory was the heaviest payload to be carried into space by a shuttle. It’s been looking at supernovae, black holes and spiral galaxies for two decades.

In 2017, when the emitted gravitational waves of two merging neutron stars reached Earth, all the major observatories in the world conducted follow-up observations on this historic, never-before-seen celestial event. The binary neutron star merger resulted in a kilonova explosion, which shone across the electromagnetic spectrum. Its x-ray emission was due to the explosion’s blast wave accelerating particles and gave us information about the material surrounding the binary. No other facility could have localized the merger as accurately as Chandra did: our understanding of one of the most important astrophysical events of modern times would be incomplete without it.

After a quarter-century of operations, Chandra is a well-oiled machine, with a highly experienced team that has adapted to the ageing telescope. Keeping Chandra up and running at the forefront of astronomy “is getting more complex, but it’s not getting costlier. We're just getting better at it every single day,” says Daniel Castro, an astrophysicist at Chandra Science Operations.

The crux of the matter lies in the presidential budget request from last March, which to communal consternation mischaracterized Chandra as rapidly degrading and increasingly expensive. A further source of frustration within the community is that NASA sidestepped its own peer-review procedure for evaluating the timeliness of mission closeout, the Senior Review (which had given Chandra top marks in 2022), by unexpectedly cutting Chandra’s funding. The budget cuts end Chandra’s mission without any discussion or input from the astrophysics community.

An interesting choice of NASA’s was to award $50 million to the development of the Habitable Worlds Observatory, or HWO, where the same funding would keep Chandra fully operational. HWO is an infrared, optical and ultraviolet NASA flagship telescope that is 20 to 30 years from launch, and which will most likely cost more than its estimated $6 to $10 billion.

Webb, whose costs ballooned from an initial $2 billion to $8 billion, looms large in the decision to prioritize funding for HWO. It’s commendable that NASA is keeping an eye on future challenges, but a lot of this first allocation of money for HWO will go into preliminary overheads, such as building a project office and establishing industry partnerships. It is worth considering whether awarding $50 million, decades before launch, to a multibillion-dollar mission justifies shutting down a mission as productive as Chandra.

Astronomers have thrown around ideas for other sources of funding for Chandra, such as selling its operations to the Japanese or European Space agencies or relying on private donations. Collaboration with other space agencies and companies is standard in astrophysics, but it is a lengthy process, and a lot of the technology in Chandra is walled off by U.S. technology transfer restrictions. And NASA’s policy directive, while it allows for donations, does not allow for conditions on their use. Besides, do we want (sometimes erratic) space billionaires to expand into fundamental science? Access to the universe is a public good, and most of us astronomers would like to avoid the possibility that oligarchs become its gatekeepers.

Killing Chandra highlights the tension inherent in flagship-style astronomical missions. They make stunning discoveries, but they also have a way of soaking up the budget of medium-size or existing missions. We need more powerful telescopes because they open new parameter space, which is the way truly revolutionary discoveries get made. But there is a delicate balance to be maintained here: What are we giving up by allocating such early funding to HWO? I’d say we’re opening a window, but closing a door. We are choosing to be blind to the high-resolution x-ray universe. And that’s a loss to science as a whole.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.