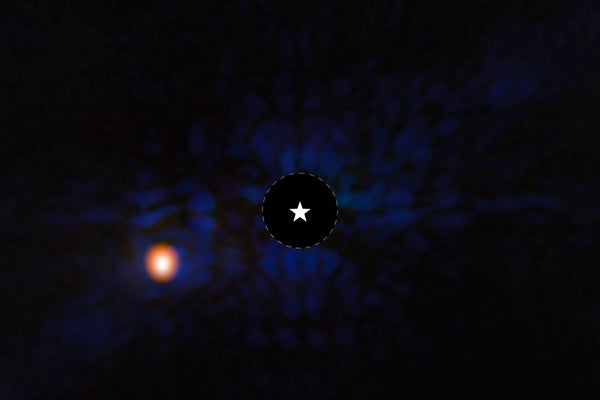

Astronomers have photographed a planet six times as massive as Jupiter orbiting one of the closest stars to the Sun. It is the first extrasolar planet to be discovered through direct imaging using the James Webb Space Telescope.

“This is a cold planet,” says astronomer Elisabeth Matthews at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. The results were published in Nature on 24 July.

“If real, the planet is by far the oldest and coldest that has ever been imaged,” says Markus Janson, an astronomer at Stockholm University.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Researchers usually detect exoplanets by tracking how they periodically cross the line of sight to Earth, temporarily dimming the light of their host stars, or because their gravitational pull causes a measurable wobble in the star itself. Only a few dozen exoplanets so far have been imaged directly, typically because they are hot and bright enough to be detectable despite their stars’ glare.

Using ‘wobble’ techniques, astronomers had already seen hints that there could be a massive object orbiting the Sun-like star ε Indi A, which lies just 3.6 parsecs (12 light years) from Earth, in the far-south Indus Constellation.

To look for a planet, Matthews and her collaborators pointed the telescope so that the star would lie exactly at the centre of its field of view. They then employed the ‘coronagraph’ capability built into one of the Webb’s onboard cameras. The instrument can sample photons at slightly different times, or phases, in each of the four quadrants of its frame. That way, when the sensor data were combined, photons from ε Indi A itself — some of which stray away from the centre — mostly cancelled out, removing the glare that would have otherwise drowned any other signal in the star’s vicinity.

The resulting image revealed a planet weighing six times as much as Jupiter, which means that like Jupiter, it must be a ‘gas giant’ made mostly of hydrogen gas, Matthews says. The planet, named ε Indi Ab, is around 15 times as far from its host star as Earth is from the Sun, and its temperature is just above 0 ºC.

Janson cautions that “the silver bullet for proving that the source is definitely a planet” — a later image that shows that the speck of light has moved — does not exist yet. But, he adds, “the study is of great, great importance, since it marks a step toward the ability to image planets in mature systems”. Previous direct-imaging efforts have been limited to observing young star systems, he says, whereas ε Indi A is nearly as old as the Sun.”

Matthews says that her team is planning follow-on observations to measure the spectrum of light from the planet. That could also reveal some of the composition of its atmosphere, which would offer hints as to where and how such a large planet might have formed in primordial nebula where ε Indi A formed.

The star forms a triple system together with two ‘brown dwarfs’ — objects that never grew large enough to trigger hydrogen fusion in their cores — that orbit it more than 1,000 times farther away than the super-Jupiter. “It’s a really unusual type of system that we’re really lucky to have in our backyard,” says Matthews.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on July 24, 2024.