I remember watching the full moon rise one early evening a while back. I first noticed a glow to the east lighting up the flat horizon in the darkening sky, and within moments the moon was cresting above it. It looked huge! It also seemed so close that I could reach out and touch it. I gawped at it for a moment and then smiled. I knew what I was actually seeing: the moon illusion.

Anyone who has seen the moon (or the sun) near the horizon has experienced this effect. The moon looks enormous there, far larger than it does when it’s overhead. I’m an astronomer, and I know the moon is no bigger on the horizon than at its zenith, yet I can’t not see it that way. It’s an overwhelming effect. But it’s not real. Simple measurements of the moon show it’s essentially the same size on the horizon as when it’s overhead. This really is an illusion.

It’s been around a while, too: the illusion is shown in cuneiform on a clay tablet from the Assyrian city Nineveh that has been dated to the seventh century B.C.E. Attempts to explain it are as old as the illusion itself, and most come up short. Aristotle wrote about it, for example, attributing it to the effects of mist.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

This isn’t correct; the illusion manifests even in perfectly clear weather. A related idea, still common today, is that Earth’s air acts like a lens, refracting (bending) the light from the moon and magnifying it. But we know that’s not right, because the moon is measurably the same size no matter where it is in the sky. Examining the physics of that explanation shows that it falls short as well. In fact, although the air near the horizon does indeed act like a lens, its actual effect is to make the sun and moon look squished, like flat ovals, not to simply magnify them. So that can’t be the cause, either.

Another common but mistaken explanation is that when the moon is on the horizon, you subconsciously compare it with nearby objects such as trees and buildings, which make it look bigger. But that can’t be right, because the illusion still occurs when the horizon is empty, such as at sea or on the plains. Also, if you’re in a city and see the moon high in the sky between buildings, it appears to be its normal size, so this can’t be the explanation.

Yet the moon does look bigger on the horizon. Experiments in the 1950s and 1960s by cognitive psychologists Irvin Rock and the late Lloyd Kaufman showed that people perceive the moon as much larger on the horizon—sometimes as much as three times bigger than when it’s overhead. If the visual cues to the position of the moon go away, however, the illusion vanishes. Looking at it through a paper towel tube, for example, makes it look the same size no matter where in the sky it is.

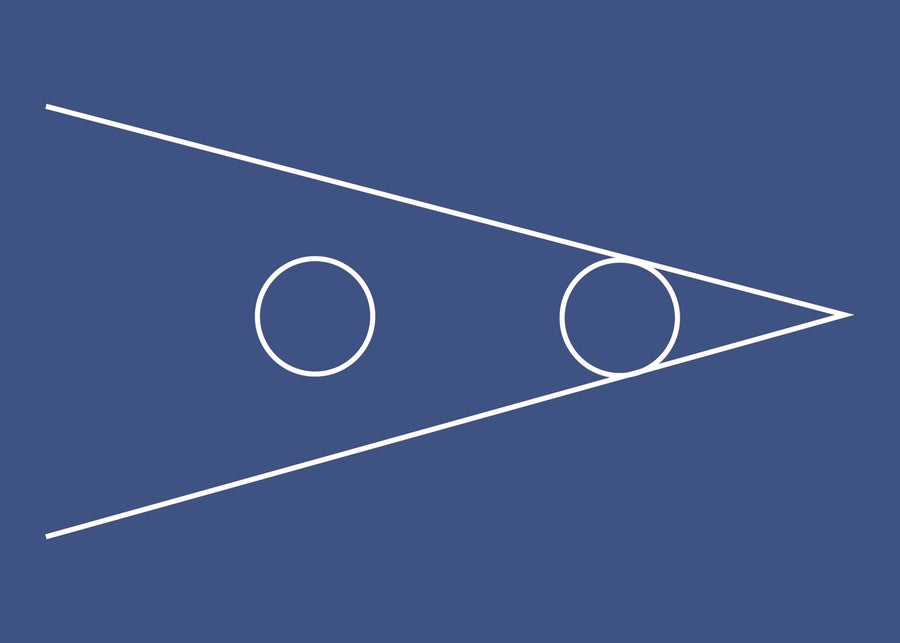

So what’s the cause? Like with so many things in science, two effects are at play. One is the Ponzo illusion (not to be confused with a Ponzi scheme, an investment illusion). It’s a very simple yet overwhelming illusion. In its simplest forms, two parallel horizontal lines of equal length (like an equal sign) are placed between two lines that are nearly vertical but converge slightly near the top. When you look at the horizontal lines, the top one appears longer even though they’re the same length. It’s almost impossible not to see them as unequal.

An illustration demonstrating a variation of the Ponzo illusion.

Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Variations abound, but all rely on tricking the brain by using perspective. We interpret the two nearly vertical lines not as leaning toward each other but as parallel yet converging in the distance, like railroad tracks. This effect, in which lines in two-dimensional space appear to meet at a point called the vanishing point, is often used in art to portray relative distances.

The key is that the two horizontal lines are the same length. Our brain sees that, but it also perceives the top line as farther away. If it’s farther away and the same apparent size, according to our brain’s messed-up logic, it must be physically larger than the lower line, so it appears bigger. This is very similar to the wonderful Ames room illusion, in which distorted walls and angles make two people of equal height appear to have wildly different sizes depending on where in the room they stand.

The Ponzo illusion is the heart of the moon illusion, but there’s more to it. If I were to ask you what shape the sky over your head appears to be, you’d probably say it’s a hemisphere—a half of a sphere. But we don’t actually perceive it that way. If we did, you’d see the zenith, the point directly over your head, as the same distance from you as any point on the horizon. Yet experiment after experiment shows that’s not the case: we see the horizon as farther away and the sky as more like a flat-bottomed bowl overhead, with the zenith closer to us.

That’s not too surprising, actually. If you’re outside on a cloudy day, the clouds over your head really are closer to you; they might be five kilometers above you, but the ones near the horizon can be more than 100 kilometers distant. So we’ve evolved to think of the sky as flattened that way.

Now put the two together: When the moon is on the horizon, we think it’s farther away. But the moon’s size in the sky isn’t actually changing, so our brain interprets this as the moon looking huge. When it gets higher in the sky, we perceive it as being closer, so it winds up looking smaller.

Amazingly, this explanation, at least in part, was determined around 1,000 years ago. The brilliant medieval philosopher Ibn al-Haytham studied vision and optics and made major contributions to both. He examined the moon illusion and correctly noted that an object of fixed size will look smaller if it’s perceived as closer and will look bigger if it’s farther away. He thought intervening objects such as trees or buildings made the moon appear closer and therefore bigger, which we now know isn’t correct. But he had the basic idea down, and he came closer than many who lived much later.

Misconceptions about the moon illusion still abound, and like so many myths, they probably won’t go away no matter how much people like me write about them. But in this case, we do know the right explanation, and it’s one of the paradoxes of science: we know why this illusion occurs, but it stubbornly persists.