Editor’s Note (6/28/24): The design of the deorbit vehicle that will be used to destroy the International Space Station will be rooted in that of SpaceX’s Dragon capsule, said Bill Spetch, operations integration manager for NASA’s International Space Station Program, during a press conference that the agency held today to discuss a range of issues related to the space station. “That’s based off a Dragon-heritage design,” he said of the forthcoming vehicle. “Obviously they have to do some modifications and some changes to the trunk for that, but that is the plan.”

SpaceX has won the right to tackle a monumental task: destroying the International Space Station (ISS). The demolition will shove the iconic and enormous station down through Earth’s atmosphere in a fiery display. And if anything goes wrong, a cascade of debris could rain down on our planet’s surface.

Conceived and built in a post-cold-war partnership with Russia, the ISS, like so many of NASA’s major projects, has lasted far longer than its initial design life of 15 years. Nothing lasts forever, however, especially in the harsh environment of outer space. The ISS is aging, and for safety’s sake, NASA intends to incinerate the immense facility around 2031. To accomplish the job, the agency will pay SpaceX up to $843 million, according to a statement released on June 26. The contract covers the development of a unique deorbit vehicle to usher the unwieldy ISS to its doom yet excludes launch costs.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

NASA has declined to provide the number of proposals received for the projects. Currently, no details about SpaceX’s vision for the deorbit vehicle are publicly known. Scientific American reached out to the company but did not receive a response by publication.

What’s clear is that SpaceX’s existing Dragon and Starship spacecraft aren’t good matches for the deorbit mission. That means the company could intend to heavily adapt one of these vehicles or to start from scratch and design a custom-built craft.

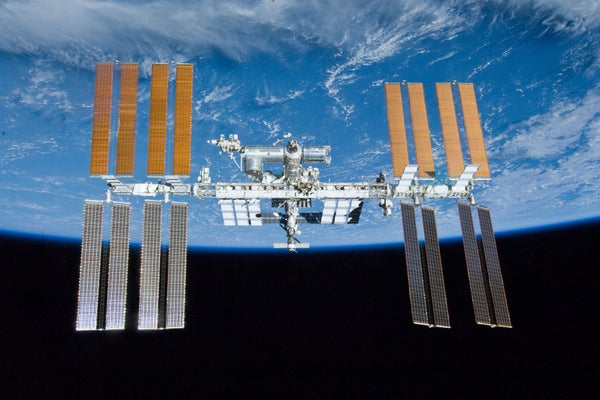

Whatever the deorbit vehicle ends up looking like, SpaceX is taking on a delicate technical challenge. The ISS is perhaps the most complex construction project ever executed—and certainly the largest and most expensive one in space. Beginning in 1998 its modules required 42 different launches to blast off Earth. And the orbiting laboratory contains about as much internal space as a six-bedroom house spread over an area the size of a football field. Weighing more than 450 tons, or the equivalent of nearly three large blue whales, the ISS is heavy, too. Safely destroying the space station arguably will be even harder than assembling it.

The ISS should still have several years of science ahead. NASA has said it intends to operate the space station through 2030 and that its partner space agencies in Canada, Europe and Japan concur with that time line. Russia’s Roscosmos, which leads the ISS partnership with NASA and operates several key modules of the station, is currently only committed through at least 2028.

But why destroy the station at all? Because of the ISS’s lengthy and continuous tenure, the last time Earth orbit was bereft of human beings was in November 2000, just before the arrival of Expedition 1, when a NASA astronaut and two Russian cosmonauts began the station’s first residency. The iconic orbital outpost is now a potent symbol of the space age and of international collaboration in science that transcends geopolitical squabbles on Earth.

Indeed, some ISS fans argue it shouldn’t be destroyed at all—instead they think it should be boosted up to an orbit so high that it would remain in space forever as a testament to the engineering prowess of humans. That idea would be wildly impractical and prohibitively expensive, NASA says. Besides, the lab is already fragile and will become ever more so the longer it stays aloft. Sooner or later, it will start disintegrating—and the more debris it sheds, the more likely catastrophic space junk collisions could become in a frightening feedback process that could curtail further activity in Earth orbit.

Some nostalgic observers want to see parts of the station excised intact and ferried safely to Earth’s surface, bound for a museum, but that’s just as logistically challenging as a permanent ultrahigh orbit, NASA says. Although the space station was assembled in orbit, it wasn’t designed to be disassembled, and no current spacecraft has enough payload capacity to carry ISS modules back to Earth.

NASA considered other scenarios, too: repurposing the facility in orbit, passing off its operation to private industry or even blowing it to smithereens in space. All posed even grimmer prospects, however.

So a fiery doom it is. And the ISS will be sent down all in one piece, given the challenges of taking the station apart. In theory, that’s a tidy solution because Earth’s atmosphere creates friction that naturally incinerates material passing through.

Larger objects can survive the inferno and fall to Earth, however. Damage from plummeting space debris is rare but not unheard of, as one Florida resident learned the hard way earlier this year, when a nearly two-pound hunk of metal crashed through his roof. The object was the remains of a large battery pallet stuffed with debris that astronauts had jettisoned from the space station three years ago for an “uncontrolled reentry,” NASA determined. The homeowner is now seeking compensation from the space agency for the incident.

When it was discarded, the pallet weighed about 5,800 pounds, according to NASA. Compare that with the station’s mass of about 925,335 pounds. A range of factors—shape, density, orientation, atmospheric conditions, and the like—determine how much of an object survives reentry. An uncontrolled plunge for something as bulky as the International Space Station would be a nightmare scenario. Not only would large pieces of the lab likely make it to our planet’s surface, but the station would also probably tumble and break apart, making the process unpredictable. And an uncontrolled reentry could rain debris anywhere along the ISS’s orbit, which passes over about 90 percent of Earth’s population.

That’s where NASA’s contract with SpaceX comes into play. The commercial deorbit vehicle is meant to launch, attach to the space station and then pull it down through Earth’s atmosphere in a carefully choreographed, risk-minimizing maneuver.

Here’s what that could look like. First, the ISS would use a combination of natural drag and, if necessary, its existing engines to move to a lower orbit, from the operating height of about 260 miles to no lower than 205 miles above Earth. Then SpaceX’s deorbiting vehicle would launch, about a year before the station’s planned date with destiny and while astronauts were still onboard.

During that one-year lead time, the ISS’s altitude would continue to decrease, and the last resident astronauts would depart for Earth—leaving the station human-free for the first time in 30 years. Depending on how quickly the laboratory was falling, the deorbit vehicle would conduct a series of burns to tug the lowest point of the station’s orbit from about 155 miles to about 90 miles.

In this region of the atmosphere, the thickness of the air would mean that the station would have less than a month left, even if NASA were to let it fall on its own. The ISS’s ability to steadily orient itself compared to Earth would also degrade. By that point, the deorbit vehicle would need to exert an iron grip on the station’s motion to prevent potential disaster.

Then, at last, the final push would be made. The deorbit vehicle would fire its engines for up to an hour to shove the ISS through the thickest, most dangerous lower layers of the atmosphere. The burn would be carefully timed to ensure that the station and whatever debris it produced fell across the sparsely populated southern Pacific Ocean, the final resting place for most of humanity’s most hazardous orbital refuse.

Throughout the entire endeavor, NASA says, SpaceX’s system must be able to successfully execute a controlled deorbit even if not one but two component failures occur.

The contract is yet another example of NASA relying on SpaceX to execute critical work. The company led the way in ferrying NASA astronauts to the orbiting laboratory and has taken over launching a host of missions for the agency. Additionally, it is four flights into testing the most powerful rocket ever flown, which is intended to be part of NASA’s complex Artemis III mission to land humans near the moon’s south pole as early as 2026.

For the mission to destroy the ISS, SpaceX will need to either substantively overhaul an existing vehicle or design something entirely new—and fast. Although NASA hopes the deorbit vehicle won’t need to launch until early 2030, the agency is aware that a stroke of bad luck on the aging station would require a scramble to fly the deorbit vehicle much sooner.

And throughout the mission, the whole world will literally be watching. Intact, the space station is already an eye-catchingly bright celestial sight, but its flaming fall will be a funeral pyre that will light up the skies—a final blaze of glory for the iconic facility and all its symbolism.