Thanks to the development of modern agriculture, the germ theory of disease and pasteurization, as well as the advent of freezers, electric ovens and fridges, millions of people can now access safe, disease-free food in many parts of the world. But despite these advances, foodborne illnesses endure. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that around 48 million Americans—one in seven—get sick from food each year.

Harmful, illness-causing pathogens lurk and fester in many different foods, from salad greens, fruit and vegetables to meat, eggs, rice and seafood. Improper food preparation and storage, lack of hand hygiene, general unsanitary conditions and insufficient cooking or reheating can all lead to food contamination. A lot of foodborne illnesses are caused by such improper handling. “The vast majority will be sporadic cases,” says Martin Wiedmann, a food scientist at the Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. “One person gets sick because one thing went wrong.”

It is possible for contamination to occur during growth of crops, animal agriculture and production procedures, however. Strict food hygiene laws and monitoring agencies (including the CDC, the Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service) ensure that the U.S. has one of the best food safety records in the world. But unexpected events or mistakes on farms or in factories can still lead to foodborne pathogen contamination. When outbreaks of foodborne illnesses do happen, experts can use DNA fingerprinting of bacteria to quickly identify the origin and recall any food that might be contaminated, helping to contain the spread.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Common symptoms of foodborne illness include upset stomach, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue and fever. In severe cases, people can be hospitalized and die. Pregnant women, elderly adults, immunocompromised individuals and young children are more susceptible to foodborne illnesses. Around 30 percent of all foodborne illness deaths worldwide occur in children under five years old.

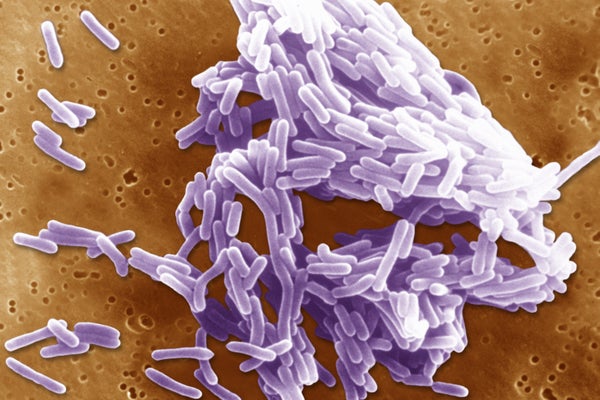

The CDC recognizes 31 pathogens as common sources of foodborne illness. Bacteria, viruses, chemicals and even parasites (such as tapeworms) can all be culprits. These are some of the major microbes you should especially watch out for.

E. coli

Escherichia coli bacteria normally live peacefully inside your intestines without harming you. If ingested, however, these bacteria can infect other areas of the body, causing diarrhea, vomiting and stomach pain. Some severe strains (such as those that produce so-called Shiga toxin) can lead to life-threatening dehydration and serious kidney damage.

E. coli can be expelled from the intestines in feces, meaning that unsanitary bathroom conditions and poor hygiene habits can all cause contamination of food. If a person gets such bacteria on their hands from direct or indirect contact with fecal matter, and then they go to prepare food or handle kitchen utensils with unwashed hands, for example, the E.coli can easily spread and become foodborne. Unclean water and unpasteurized beverages (such as raw milk) can also spread E. coli. Farmed produce also carries an E. coli risk – particularly if wildlife or livestock feces come into contact with the bacterium.

“E. coli is often associated with cattle and other ruminants,” says Martin Bucknavage, food safety and quality specialist at the Pennsylvania State University’s Penn Extension, which focuses on agriculture. “It could be cows, sheep, even white-tailed deer—it’s in their intestinal tract.” Contamination can occur if an infected animal’s feces get into water supplies and crops. This route is thought to have caused a number of E. coli outbreaks in produce, such as one in spinach in 2006. But this type of pathogen exposure has decreased in recent years, partly because farmers have been better at controlling livestock waste, Bucknavage says. “The meat industry has done a lot of work to try to minimize it.”

Salmonella

Salmonella bacteria are most often associated with raw chicken and eggs, and ingesting food contaminated with them can lead to symptoms such as fever, diarrhea and stomach cramps. The bacterium is estimated to infect more than one million people in the U.S. every year.

“Big industry has a lot of strategies in place to reduce the risk of Salmonella,” Wiedmann says. But eating certain foods raw or unprocessed, such as raw eggs or unpasteurized milk, can cause outbreaks, including the recent Raw Farm milk company outbreak this year. In addition to eggs, unpasteurized milk and raw chicken, foods from which people have gotten sick include peanut butter, raw pork, raw beef and cucumbers. Raw flour also be a source of salmonella infection, so people should avoid consuming raw cookie dough and cake mix.

Like E. coli, Salmonella lives in the intestines of humans and other animals and can be caught through contact with feces. It can also be found on the skin and fur of many animals, especially in warm climates. “A lot of our food supplies are coming from these warmer areas where there's a lot of wildlife,” especially lizards, Bucknavage says. “So it can get onto crops that way.”

Birds, hedgehogs, turtles, guinea pigs and even pet bearded dragons can all carry Salmonella and cause contamination through direct or indirect contact.

Listeria

Named after Joseph Lister, a British surgeon who pioneered the use of antiseptics in surgery, Listeria is another genus of bacteria that can potentially cause nasty infections if ingested. Preventing Listeria contamination can be a challenge, Bucknavage says. “It’s one that has the ability to grow at refrigeration temperatures,” he adds. Listeria contamination is especially difficult for manufacturers to prevent.

“Companies go to great lengths to try to control it within those processing environments,” Bucknavage explains. But despite these efforts, Listeria outbreaks can still occur. The deli meat brand Boar’s Head recently recalled millions of pounds of meat after foodborne Listeria caused at least two deaths and several dozen hospitalizations across more than a dozen states. “It has a high mortality rate compared to other pathogens,” Bucknavage says. “If it enters the bloodstream, it can lead to a blood infection, or septicemia, or it can infect your neural system, leading to things like meningitis,” or inflammation of the brain and spinal cord.

Infected people can experience aches, diarrhea and vomiting. High fever, severe headache, confusion, neck stiffness and sensitivity to light are all signs of bacterial meningitis, and people with these symptoms should seek medical care immediately.

Despite the horrible effects the bacteria have when ingested, recent research has been looking at the possibility of using Listeria as a cancer vaccine. This research is in its early stages, however, and Listeria is still very harmful in its unaltered, foodborne state.

Norovirus

Norovirus is a genus of very contagious viruses that can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and stomach pain. These symptoms start around 12 to 48 hours after infection and usually last one to three days. Colloquially known as a “stomach bug” or “stomach flu,” this foodborne illness is estimated to sicken around one in 15 people in the U.S. each year.

“Norovirus is one that easily spreads throughout a population,” Bucknavage says. And people themselves, rather than food production, are typically the culprit. “Somebody goes to work, and they're ill, and then they handle food, and it spreads very easily, person to person [or] person to food.”

Part of the Caliciviridae family of viruses, Norovirus causes the stomach and intestines to swell, initiating gastroenteritis. The viral illness usually runs its course in a few days, but it’s important to drink plenty of fluids to stay hydrated. You should seek medical help if you’re a member of a vulnerable group or if your symptoms don’t improve.

How can you avoid foodborne illness?

Fortunately, a major way to help prevent becoming infected is pretty simple: wash your hands with warm water and soap before preparing, cooking and eating food. Doing so after using the bathroom, picking up dog waste or changing diapers is also important, as is carefully cleaning food preparation surfaces, cutlery and chopping boards after they’ve come into contact with raw meat.

Meat thermometers are also great tools to help you tell if food has reached the necessary temperature to kill most microbes. The temperature needed to heat certain meats and fish can vary. The USDA recommends reheating food to an internal temperature of at least 165 degrees Fahrenheit (74 degrees Celsius).

There are the four basic practices to avoid infection from foodborne illnesses, Wiedmann says: “cooking, chilling, [avoiding] cross contamination, cleaning or washing your hands right before you prepare food.” The CDC emphasizes these “four steps to food safety." Wiedmann notes, “If you combine those four things, you can substantially reduce your risk of foodborne illness.”

What to do if you have food poisoning

Hydration is vital when you think you’re dealing with foodborne illness. Healthy adults often find their symptoms get better after several days. But if the symptoms persist or the sick person is from a vulnerable group, medical attention might be necessary. The CDC recommends that individuals seek medical advice if they have the following symptoms: bloody diarrhea, fever above 102 degrees F (39 degrees C), diarrhea lasting more than three days, frequent vomiting and severe dehydration.

You can find more info about current foodborne illness outbreaks in the U.S. here.