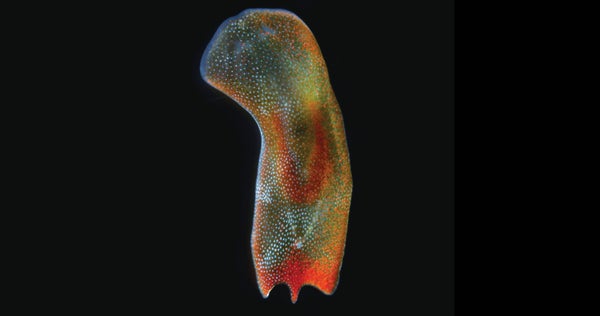

At first glance, tiny flatworms called acoels seem pretty simple. Their few internal organs drift freely in their shapeless bodies, which lack even a digestive tract.

Some acoel species host photosynthesizing algae that provide energy in exchange for safe housing, a classic example of symbiosis. And these acoels can do something remarkable: if cut in half, they split into not just two but three new, thriving versions of themselves. First a single new tail grows from the head, and then two Hydra-like heads erupt from the tail before it splits into two more separate organisms. Now a study in Nature Communications suggests these worms manipulate their live-in algae’s gene activity during this extreme act of regeneration. Scientists find this intriguing because many coral species also depend on symbiotic algae—which today’s warming seas are increasingly forcing to abandon their hosts, causing coral bleaching and sometimes the collapse of entire ecosystems.

Study co-author Bo Wang and his colleagues found that when they intentionally injured acoel worms, the algae’s photosynthesis became less efficient as the worms began to regenerate. But simultaneously, the algae’s photosynthesis genes became more active, potentially compensating for the shortfall. Experimentation suggested that a worm gene called runt, when activated to help regeneration, likely made a protein that prompted the algae to switch on these particular genes. “Here the host cells are directly regulating the algal cells, potentially for the benefit of the host system,” says Wang, a developmental biologist at Stanford University. “The photosynthetic pathway being controlled by the regenerative program of the host—that was the most surprising thing for us.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“A lot of studies tend to look at symbiosis from the animal side because people are interested in the animals more than the algae,” says Yixian Zheng, a developmental biologist at Carnegie Science in Baltimore, who studies algae-harboring corals. “This paper’s strength is that they focus on the response of the symbiont, the algae, directly connecting the algae response to the host regeneration.”

Learning how hosts control their algal partners could help researchers manipulate the algae within corals and possibly restore interactions that are lost because of stress, Wang says. He’s also curious about how the algae that benefit acoels seemingly control their landlords in turn—for instance, how the algae sometimes prompt the usually photophobic worms to spread out like solar panels, exposing the resident algae to the sun.