This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

This Thanksgiving, as you’re slipping into a drool-ey, turkey-and-pie coma, and your bouncy teenage cousin is pawing your face to get you off the couch for a game of touch football, wonder no longer why the two of you have had drastically different responses to the same meal.

It’s because you’re old.

Just kidding, kind of. Age is probably a part of it, but a new study published this week in the journal Cell found that blood glucose responses between individuals to even the same foods can vary widely. This has implications beyond your ability to participate in après-binge physical activities.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

High blood glucose is related to a host of health problems, including type II diabetes, liver disease, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease. Many popular diets focus on the glycemic index of foods—that is, the speed and magnitude with which a food raises blood glucose. Foods with simpler, refined starches and sugars tend to have higher glycemic indices, like white bread and sugary drinks—versus lower-glycemic whole foods, like chicken or Brussels sprouts.

This study indicates that by sticking to broader (and rigid) eat-this, don’t-eat-that prescriptions, some people may be eating foods that spike their blood sugar more than they’d expect, or missing out on foods that actually wouldn’t affect them all that negatively.

The researchers recruited 800 participants to wear Continuous Glucose Monitors for seven days, while also logging activities like meals, sleep and exercise in real time, using a smartphone and web app. Throughout the week, the glucose monitors measured blood glucose every five minutes, resulting in a final data set of 1.5 million measurements. While instructed to carry out normal daily activities and eating habits throughout the week, participants also received standardized meals for the first meal of every day. This allowed the researchers to monitor the various blood sugar responses to a standard identical meal, in addition to different, real-life meals. In total, 46,000 meals were recorded along with their blood glucose response.

In the lead-up to the week of glucose monitoring and food logging, participants also provided lifestyle information, like sleep and exercise habits; blood tests; and a stool sample that was used to profile participants’ microbiome—the trillions of bacteria living in the human gut—which has been increasingly recognized as an important player in a multitude of health outcomes.

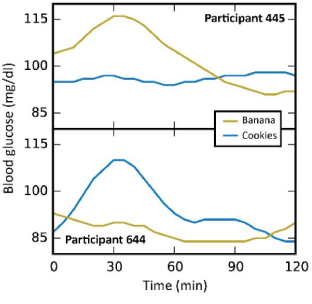

The data analysis revealed a high level of variability in glucose responses to identical meals among participants. Because they standardized some of the meals, the researchers were able to verify that the glucose response to the same meal for the same person at the same time of day was consistent—yet between participants, responses to the same meal could be very different.

For example, look at participants 445 and 644 below. They pretty much had opposite blood glucose responses to bananas and cookies. That’s bananas!

All these data were used to create an algorithm meant to predict blood glucose responses to specific foods based on individuals’ lifestyle factors (like exercise, sleep, BMI) and microbiome features (like the presence of specific bacteria phyla). This algorithm was then validated on a new independent cohort of 100 individuals, who had had the same baseline measurements taken. Based on those measurements, the researchers were able to predict with relative accuracy, the blood glucose response to certain foods for those individuals.

Finally, in a follow-up randomized blinded study, the researchers used the algorithm they created to assign participants either “good” or “bad” diets, based on those individuals’ baseline lifestyle and physiological features. The “good” diets consistently resulted in lower blood glucose responses to meals, and the “bad” diets, conversely, resulted in higher glucose responses. Notably, many of the foods that the algorithm included in the “good” diets for some participants, were “bad” foods for others. This points to the high variability between individuals’ responses to different foods.

In addition to better blood glucose control, the personalized “good” diets also resulted in changes to the gut bacteria that are associated with positive health outcomes. Some bacteria that have been associated with better glucose control were more prevalent after implementing the “good” diet. The research on this is young, so it’s not clear to what extent those “good” bacteria are causing the health benefits, versus simply proliferating due to changes in dietary intake. It’s probably a bit of both.

“The microbiome is complex, and I believe there really is a symbiosis,” said Eran Segal, PhD, one of the authors of the study. “If you change your diet, there is an obvious result that diet changes the microbes, but those microbes are also going to have an effect on you.” He said.

The researchers are planning a longer-term follow-up study that will test and refine their algorithm among people at higher risk for diabetes. They have also licensed their work to a company that offers personalized nutrition plans based on people’s unique microbiomes.

“We started this study four years ago as scientists,” said Segal. “As scientists we are motivated by curiosity. Given the lack of evidence of a lot of nutritional advice, we wanted to do a scientific, unbiased approach to nutrition. We’re licensing the technology to a company which is working to develop it further to bring it to the masses. If it’s done in the proper fashion it has the potential to really improve people’s health.” He said.

Segal and I discussed the fact that dieting doesn't seem to work for most people in the long term. Segal pointed to this study as evidence that the variable response to different foods could be responsible for the high failure rate of diets. Many people lack the time, knowledge, or resources to make healthy food a part of their lives. But of course, there are plenty of people who are able to overcome those barriers, and they often become very tribal and vocal in their insistence that their particular diet is the only way (think paleo or vegan).

“This study shows that there cannot be one solution that can work for all,” Segal told me. “Many of the diets out there have no or very little science backing them up . . . It’s very easy to pick any diet and cherry pick people that it works for and hold them up as examples of its success.”

Segal said the vision for this technology is to refine the model, and in the end, to bring it very broadly to the general public—accessible to individuals, but also to be used by insurance companies and government health services.

If they are successful, this may be the first nail in the coffin of a diet industry that has largely been based on anecdotes and hype.

Look out, fad diets, the bar has been raised… With science!

Illustrations by author