Microscopic tardigrades—plump, eight-legged arthropod relatives—are nearly indestructible, and their durability superpower may have helped them weather the deadliest mass extinction in Earth’s history, according to a new fossil analysis.

Tardigrades, also called water bears, can withstand extreme heat, cold, pressure and radiation. Two major tardigrade lines survive hostile environments through a process called cryptobiosis, in which they lose most of their body’s water and enter a suspended metabolic state.

There are only four known tardigrade fossils. All are preserved in amber, including two inside a pebble that was found in Canada in 1940 and dates from 84 million to 72 million years ago. One of the pebble’s tardigrades, representing a species named Beorn leggi, was described in 1964. The other was too small to be identified at the time, says Marc Mapalo, a graduate student at Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

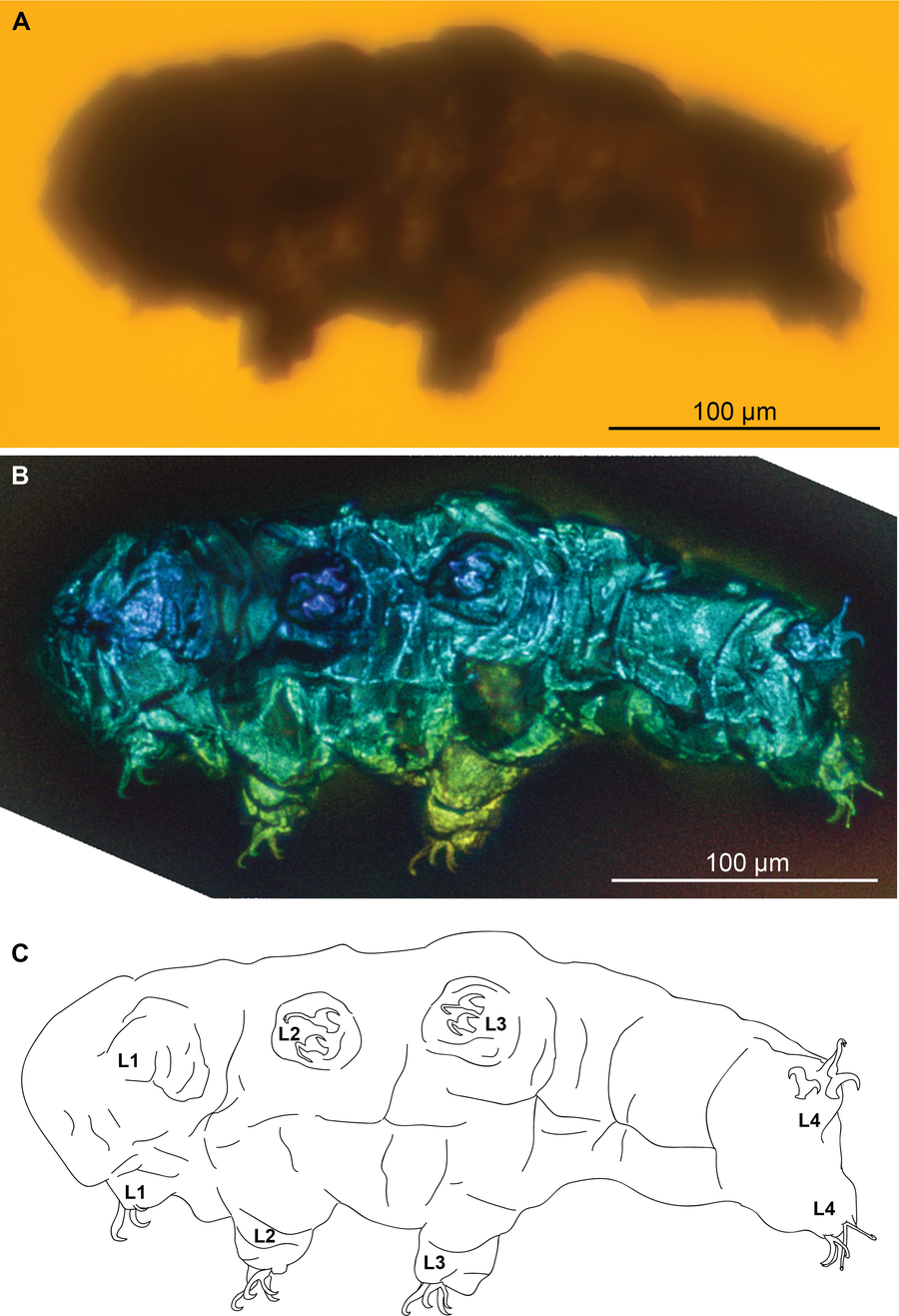

The tardigrade Beorn leggi, photographed with transmitted light under a compound microscope (A), photographed with autofluorescence under a confocal microscope (B) and represented as a schematic drawing (C).

For a new study in Nature Communications Biology, Mapalo and his colleagues used high-contrast microscopy to uncover previously unseen details in both specimens’ claws, “which are very important taxonomic characteristics in tardigrades,” Mapalo says. Tardigrade body plans have varied little for millions of years, so the small visible differences in claw shape offered crucial information about where in the tardigrade family tree these amber-trapped fossils belonged, says University of Chicago organismal biologist Jasmine Nirody (whose own work has also examined tardigrade claws).

The authors determined the smaller tardigrade was a new genus and species: Aerobius dactylus. They also revised B. leggi’s description and classification based on its claw joints. Both species were placed in the same tardigrade superfamily Hypsibioidea, and B. leggi was moved into the family Hypsibiidae. Reclassifying B. leggi based on previously unseen details clarified its relationship to living tardigrades.

The resulting family tree recalibration allowed the researchers to calculate when the two tardigrade lines that perform cryptobiosis could have diverged—putting a latest date on the likely acquisition of that skill. Their work suggests cryptobiosis appeared in tardigrades during the Carboniferous period (359 million to 299 million years ago), predating a deadly event known as the Permian extinction, or the “Great Dying,” which occurred about 252 million years ago. The authors suggest that cryptobiosis may have helped tardigrades survive the event, which wiped out 96 percent of marine life and 70 percent of life on land.

Cryptobiosis’s evolution is challenging to study, partly because tardigrade fossils are so scarce, Mapalo says. Additional fossil discoveries will help scientists pin down details about the appearance of this unique survival strategy. By sharing this result, he says, “we hope we will entice other people to be aware that fossil tardigrades exist and there are still more to be found.”

Editor’s Note (9/16/24): This article was edited after posting to correct the descriptions of the how the findings helped researchers reclassify the tardigrade family tree and when Beorn leggi was first described.