There aren’t many scenarios in which getting a good look at a bunch of Komodo dragon teeth ends well. The massive lizard’s mouth holds 60 serrated teeth, each up to an inch long, that get replenished throughout the creature’s life. And dangling from the serrations are the remains of previous meals, plus dozens of bacteria that feast on them.

To be fair, Aaron LeBlanc, a paleontologist at King’s College London, got his close look at Komodo dragon teeth minus the grizzly decor and detached from their ferocious owners. His examinations paid off. “Every now and then, I would see this sort of orange discoloration to the outer layer of the teeth,” LeBlanc says. “I honestly probably saw it three, four times and just dismissed it as staining from feeding.”

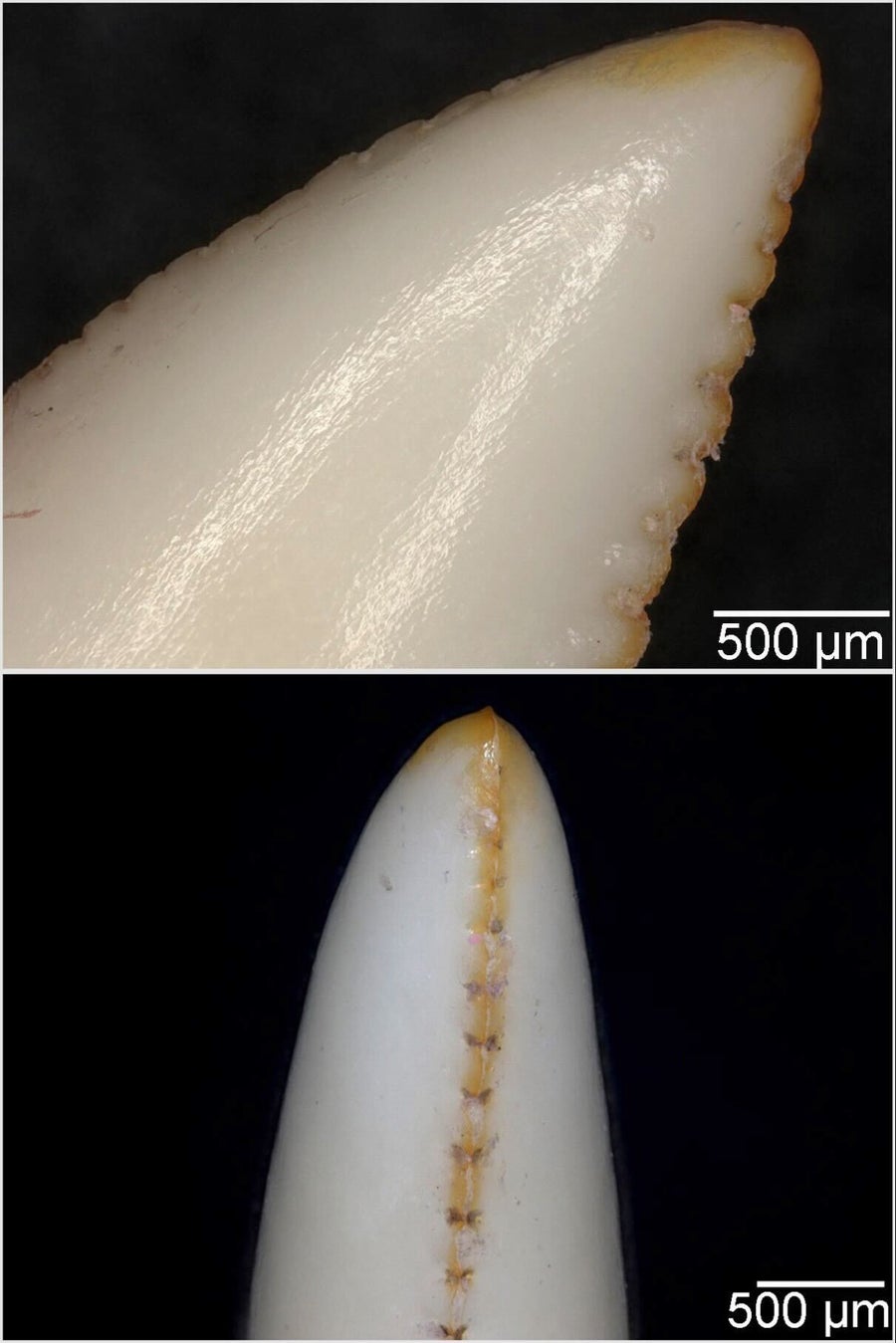

But closer inspection proved that the orange hue LeBlanc saw on the serrations and tips of Komodo dragon teeth was iron that was present before they ever took a bite. The result, described in research published on July 24 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, is the first confirmed finding of iron chompers in reptiles. (Some fish and salamanders, as well as a handful of mammals—most notably beavers—are also known to include iron in their teeth.)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Reptilian teeth have long been considered simple and cheap because they grow quickly and get replaced several times throughout their owner’s life. Research like that in the new paper is changing that perception, however. “We’re basically just starting to scratch the surface into how complex reptile teeth can actually be,” says Kirstin Brink, a paleontologist at the University of Manitoba, who studies teeth but was not involved in the new study. “Now that we’re starting to actually take a closer look at different reptiles, we’re finding all of these really cool adaptations.”

Close-up images showing orange serrations running down the front and back of a Komodo dragon tooth.

Komodo dragons, which can grow up to 10 feet long and live on a few islands in Indonesia, are typical reptiles in terms of teeth replacement, LeBlanc says. “They’re basically tooth factories,” he adds. The tip of each pointed tooth curves back into the animal’s mouth, which allows it to tear off and swallow large chunks of meat. And the iron reinforcement is strategic as well, LeBlanc says. The orange detailing precisely marks a single line of serration running down the front and back of each tooth—with the serrations more pronounced on the back—and marks the tooth’s tip: puncture, pull, swallow, repeat.

LeBlanc was drawn to the giant lizards’ teeth because of their pointed, curved profile, which would look at home in the smiles of even more fearsome animals: dinosaurs. Such comparisons are a valuable approach for paleontologists, Brink notes. “When we’re studying fossils, especially when we’re trying to interpret behaviors which we can no longer observe because the animals are dead, we have to look to modern analogues,” she says.

Inspired by the Komodo dragon finding, LeBlanc and his colleagues looked for signs of similar iron reinforcement in the teeth of other living reptiles and dinosaurs. They discovered that a few different species of monitor lizards had the adaptation, though to a lesser extent, and that some crocodilians showed signs of iron in their teeth as well. For the dinosaur teeth, the team found iron throughout, but think it was likely deposited from the fossilization process, given the abundance of iron on Earth’s surface. “Iron is probably the worst thing to look at in fossil reptile teeth,” LeBlanc says. “If you bury a dinosaur tooth in the ground for tens of millions of years, iron will eventually seep into every nook and cranny.”

Still, he and Brinks agree, the research suggests that scientists should take a closer look at teeth in living reptiles and dinosaurs alike, with eyes peeled for unexpected dental adaptations like those of the Komodo dragon. “We shouldn’t take for granted how complex reptile teeth can be,” LeBlanc says.

A version of this article entitled “Iron Chompers” was adapted for inclusion in the November 2024 issue of Scientific American.