When you’re struggling through a case of the common cold, the snot pouring from your nose seems endless. You go through countless tissues to mop up all the chunky, bright yellow boogers and thin, runny mucus, heaping up mountain ranges of used tissues.

And while you try to comfort yourself with hot soup and over-the-counter medications (many of which don’t do anything at all), a question pops into your head—how much mucus does someone actually produce while they’ve got a cold?

It must be enough to fill at least a coffee cup, you’re sure. Or a sink maybe? Or even a car? Surely someone must have attempted to measure this for the sake of sinus science.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As it turns out, only a few intrepid scientists have collected Kleenex for the common good. And from what these brave researchers have found so far, the amount of mucus produced through our valiant viral suffering may not be as much as we think.

Mucus plays an astonishing number of useful roles in the human body, from lining our intestinal tracts and sliming up our poop to working as nature’s lube for sexual activities involving vaginas. The slick combination of water, salts and gel-forming proteins called mucins that make up mucus also helps trap dust, allergens and infectious particles in the nose, mouth, windpipe and lungs. This congealed mass of sticky mucus and unwanted particles is then swept up with the help of tiny, hairlike structures known as cilia, and dumped at the back of the throat where it’s usually swallowed—hopefully without you noticing (until someone points out that’s what’s happening; you’re welcome). Overall, even without a cold, our bodies produce quite a lot of mucus, over 1.5 liters per day. You’re gulping down a solid large ice cream container of snot every day, even when you’re not sick.

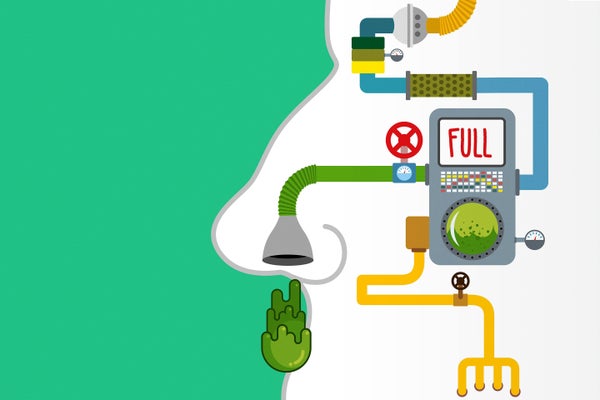

But get a cold and it can feel like bucketloads more. Since mucus is also poised to act as a major immune response when we get sick, mainly due to its sticky consistency, booger production gets pushed into overdrive. Blood flow gets rerouted to the nose, swelling up the nasal tissues and making it hard to breathe (the reason you still can’t get a good breath no matter how much you blow). Submucosal glands and cells called goblet cells pump out gobbets of mucin proteins. The mucin proteins fill up with water, and the resulting overflow comes out as a tsunami of snot—hopefully also flushing out harmful virus particles in the process.

But exactly how much goop a cold produces is a difficult question to investigate, not least because of all the variables involved. There are at least 160 strains of rhinovirus that produce the symptoms we call the common cold—each causing a slightly different immune response—and other viruses, such as coronaviruses and RSV, can also trigger varying coldlike symptoms. People are also known to respond differently to the same infection—one may be very slimy while another remains relatively dry. Individuals who live in dry climates may have drier mucous membranes than those in humid ones. So, when scientists attempt to research colds, they must try to minimize these variables; this means infecting study participants with a single type of rhinovirus or coronavirus at a time, and monitoring them through the course of their symptoms.

With most previous studies examining the common cold—mainly testing out different drugs to ease symptoms—researchers have measured things like subjective nasal congestion scores, or even how much air you can sniff up your nose, instead of anything to do with discarded tissues or snot volume. This is because effectively collecting snot samples can be quite difficult: as mucus is mostly water, asking people to collect their used tissues over time means that the water will evaporate, leading to unreliable results. Collecting tissues would also mean more than one visit to a lab, costing money and time for participants and scientists alike.

But a few courageous scientists have taken up the task of snot collection. A 1993 study by D.A.J. Tyrrell and colleagues at the Center for Applied Microbiology and Research in England infected 116 volunteers with either a coronavirus (one of the cold-causing kinds, not a pandemic-causing kind) or one of three types of rhinovirus and quarantined them for up to five days after infection. To study their mucus ejection volume, the scientists collected used tissues in sealed plastic bags and then weighed them against non-mucus-filled bags of tissues. After all that, however, they never reported the actual volume or weight of the snot rockets. Instead, the scientists simply noted that 60 percent of people experience an increase in mucus weight, and up to 70 percent had a “nonzero tissue score” (meaning they used at least one tissue) two days after inoculation.

Our true loogie heroes came through in a 1990 study out of Australia, where Carol Pinnock and colleagues at the University of Adelaide were investigating the supposed wisdom that drinking milk or eating dairy products during a cold makes you produce more boogers. The scientists gave over 50 college students from around Adelaide a rhinovirus and had them collect their used tissues in plastic bags and keep food diaries. They then weighed the bagged specimens, categorized them by whether the person ate a little, moderate, or large amount of dairy, and recorded the difference, giving us our first ever specific set scientific results on how much mucus we produce.

The clincher: it’s not that much. The researchers concluded that the average mucus shot into tissues during a cold was the pitiful amount of between zero and 30.4 grams per day. This is only about the average mass of half a tennis ball! So not exactly sink-sized amounts of nasal excretion, nor coffee cup size even. The dairy products were also found to have no significant effect, even though some students drank up to 11 glasses of milk per day (for reasons unknown).

To those of us surrounded by tissues during some colds, 30.4 grams seems low. More and better studies of the boogers we produce are necessary. Maybe it’s the congestion that makes us feel we’re drowning in boogers? Perhaps some people are super-snotters? But it is a comfort, at least, to know that the gross, gelatinous piles that end up in our tissues serve a purpose. The mucus is our immune system rising to the challenge, shoving virus out of our bodies with our snot. Our bodies are defending us in the best way they know how—with lots and lots of boogers.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.