After about 15 years of diving at the White Sea Biological Station in Russia, marine biologist Alexander Semenov has learned more than most about which jellyfish stings are the worst. If you touch the egg-yolk jellyfish by accident, for example, it is not too bad, he says. And though you should try and stay out of the way of a lion’s mane jellyfish, if you see a glimmer of sun illuminate even one of the jelly’s “mane” of up to 150 threadlike tentacles in front of you, it is too late. “The next moment, these tentacles just go on your lips, and it hurts,” Semenov says.

Such are the hazards that come with documenting the strangest life-forms floating, shimmying and pulsing through our oceans—not to mention the brutal cold. The day he spoke with Scientific American, Semenov had just been in 35 degree Fahrenheit water, which felt warm, compared with the 30 degree F diving temperatures of the previous couple of months.

Semenov puts up with it all, even repeatedly visiting sites at specific times, to find the aquatic life he is looking for. But to him, no part of his job feels like an exercise in patience. “I just love all this stuff,” Semenov says. “And I can spend months and years in the same place, diving and looking.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Alexander Semenov

Venus’s girdle, a species of comb jelly, or ctenophore. Normally invisible, this gelatinous creature becomes iridescent when it is disturbed. It rolls up to protect its stomach (purple horizontal bar) and neural hub from predators. “Fish will need to eat a lot of slime before getting to the center,” Semenov says.

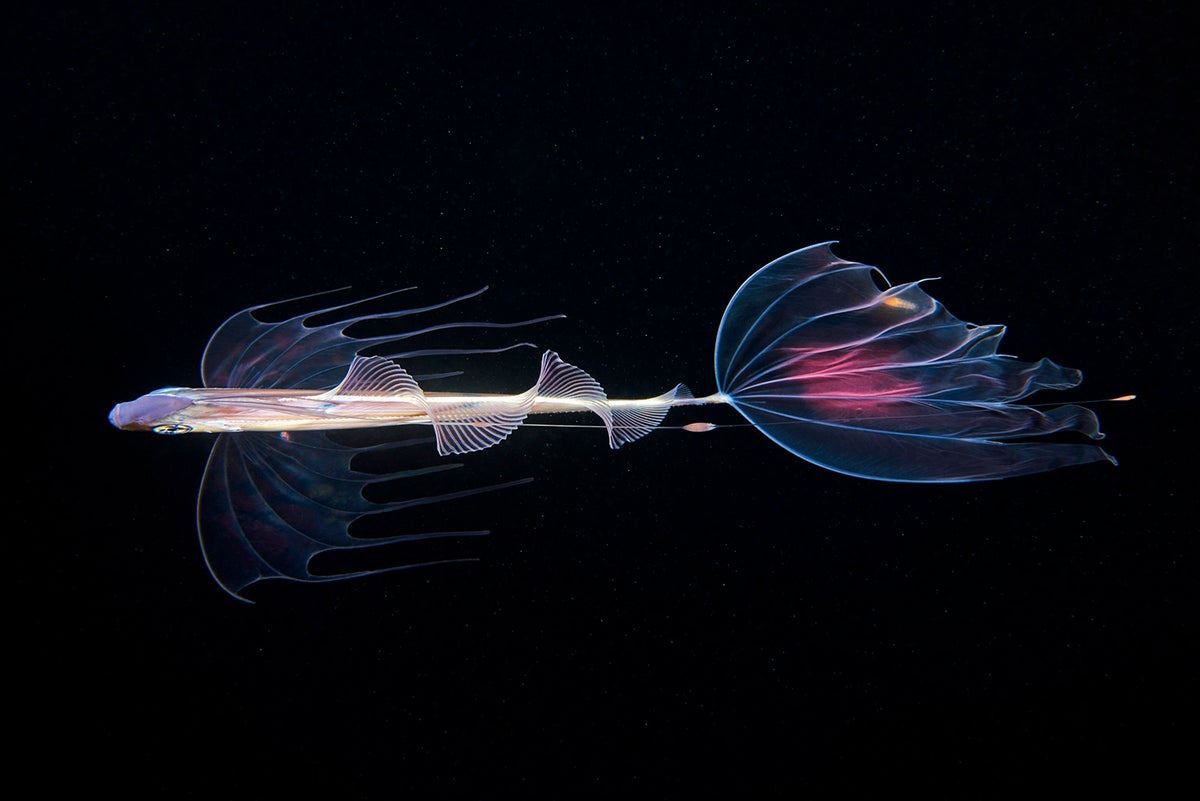

Credit: Alexander Semenov

Mediterranean dealfish: The species swims vertically and lets its nonfunctional tail fin drift behind. If the electric violet dome and delicate wisps of tissue look familiar, that is the point: the Mediterranean dealfish’s goal is to confuse prey into thinking it is a jellyfish.

Credit: Alexander Semenov

This comb jelly houses a hyperiid amphipod (pink mass with black eyes at right). These parasitic amphipods bore to their host’s stomach, sometimes in large enough numbers that the victim looks more like a strainer than a jellyfish or ctenophore.

Credit: Alexander Semenov

Egg-yolk jellyfish near Kamchatka Peninsula in eastern Russia. These jellies turn bright yellow as they age. And though somewhat stingy, the tentacles are also sticky, giving the species two ways to ensnare prey.

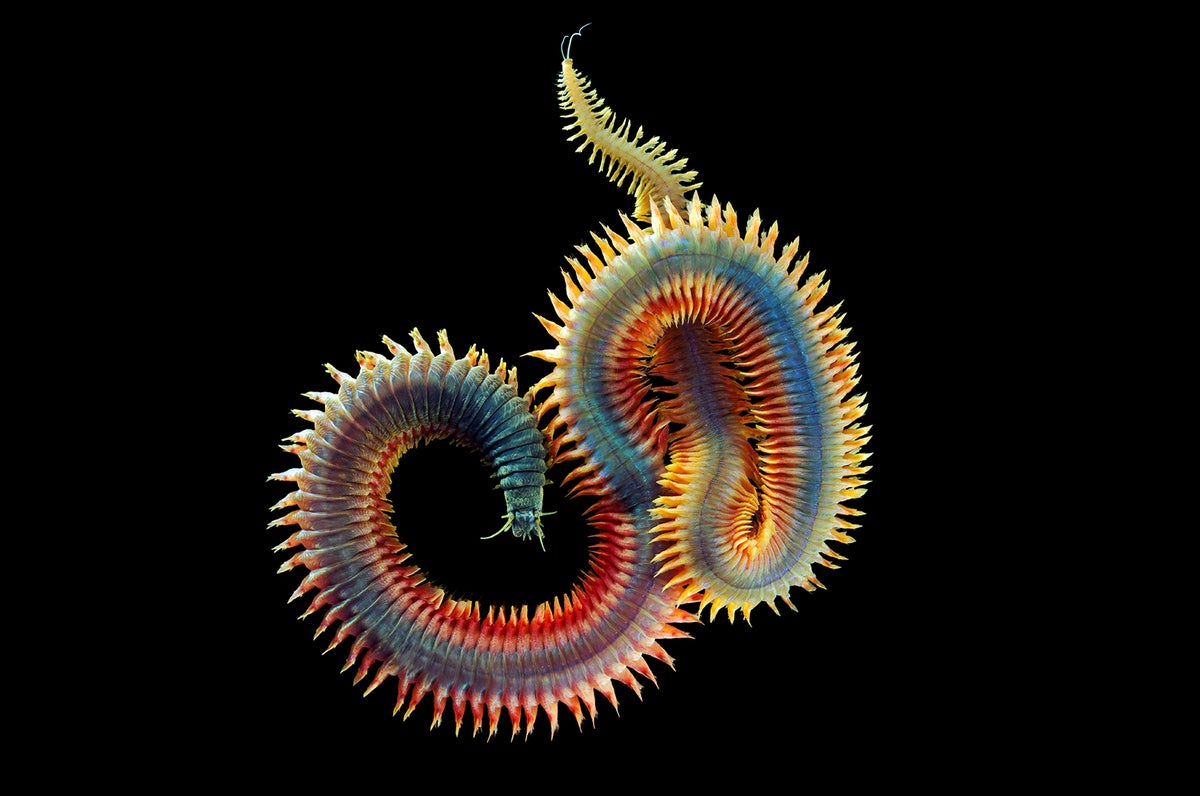

Credit: Alexander Semenov

King rag worm: This North Atlantic and Arctic resident is the seafloor’s favorite snack, which is why it lives in cracks and catches prey by ejecting its jaws up to a quarter of its body length away.

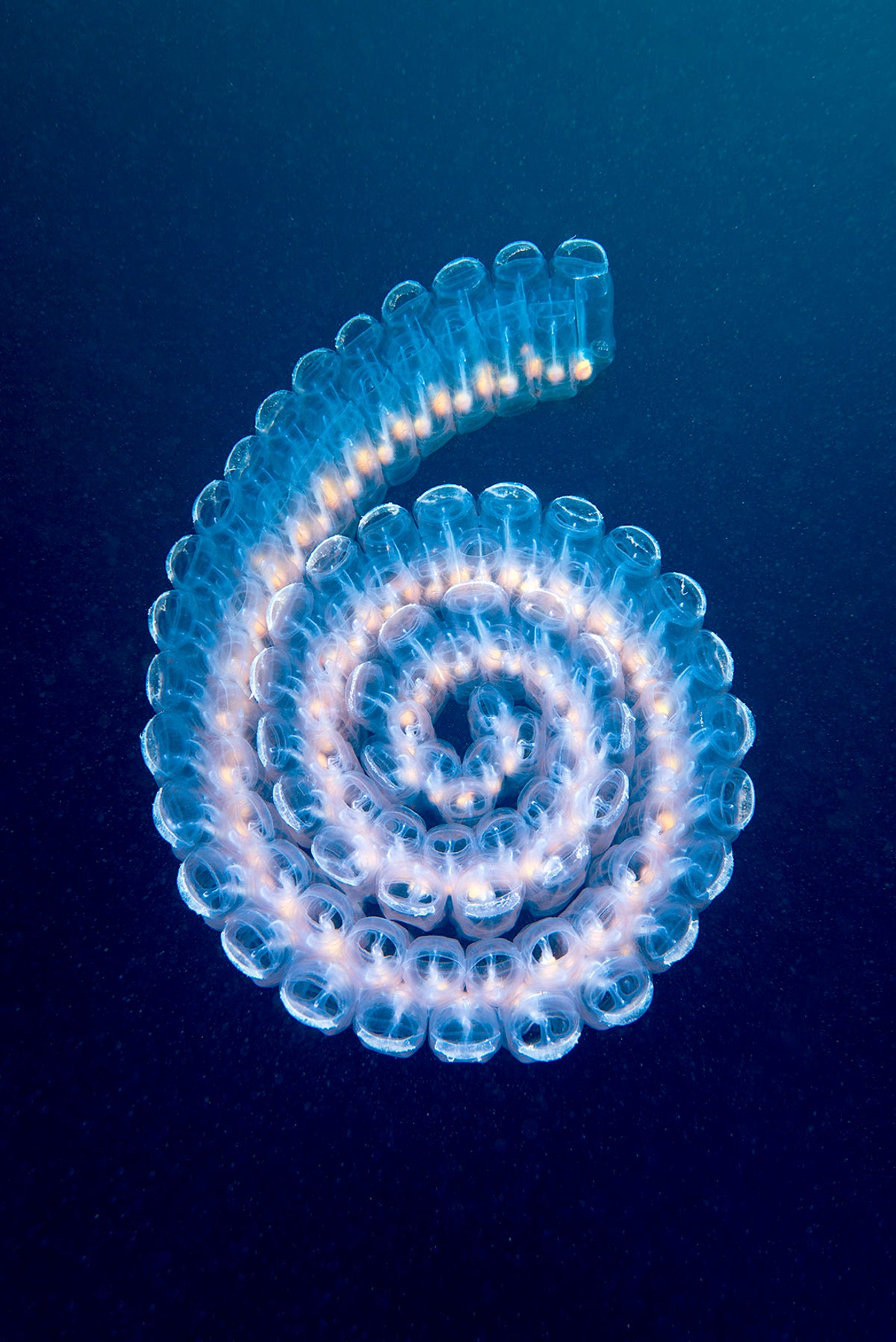

Credit: Alexander Semenov

Colony of salps, a type of sea squirt, living side by side in a spiral. These barrel-shaped filter feeders have a protective rod running the length of their nerve cord while young, making them and other sea quirts our closest relatives among invertebrates.

Credit: Alexander Semenov

Salp spiral from above: The creatures band together in colonies that can reach up to 26 feet long. Each member filters so much water that, depending on the salps’ numbers, their fecal droppings might shift the ocean’s carbon cycle.

Credit: Alexander Semenov

Sea butterfly in the Sea of Japan: The maximum wingspan of these free-swimming mollusks is only a centimeter (0.4 inch). But Semenov has seen the White Sea go almost black as thousands of sea butterflies and their dark shells filled the water.

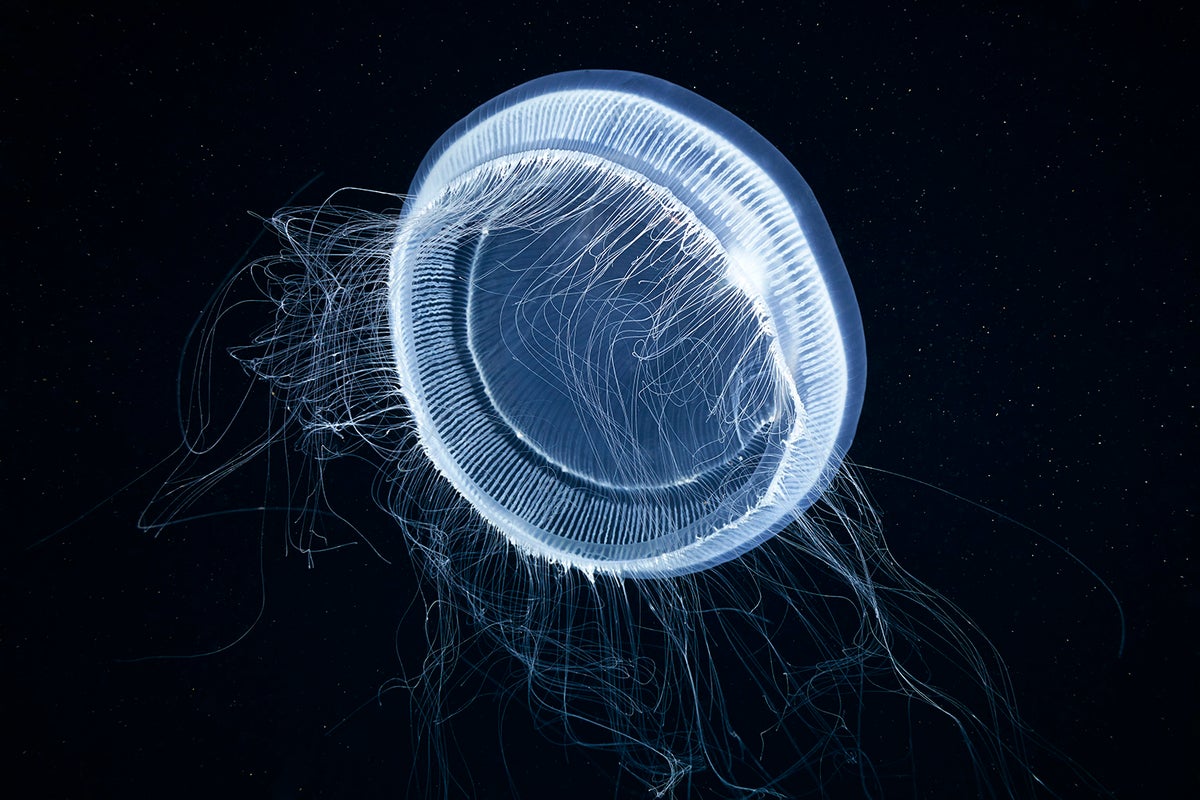

Credit: Alexander Semenov

Crystal jelly glow in the dark, thanks to green fluorescent protein. The researchers whoidentified and isolated the protein and developed its use as a fluorescent tracking device in other biological systems earned a Nobel Prize for their work.