An artificial intelligence (AI) network developed by Google AI offshoot DeepMind has made a gargantuan leap in solving one of biology’s grandest challenges — determining a protein’s 3D shape from its amino-acid sequence.

DeepMind’s program, called AlphaFold, outperformed around 100 other teams in a biennial protein-structure prediction challenge called CASP, short for Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction. The results were announced on 30 November, at the start of the conference — held virtually this year — that takes stock of the exercise.

“This is a big deal,” says John Moult, a computational biologist at the University of Maryland in College Park, who co-founded CASP in 1994 to improve computational methods for accurately predicting protein structures. “In some sense the problem is solved.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The ability to accurately predict protein structures from their amino-acid sequence would be a huge boon to life sciences and medicine. It would vastly accelerate efforts to understand the building blocks of cells and enable quicker and more advanced drug discovery.

AlphaFold came top of the table at the last CASP — in 2018, the first year that London-based DeepMind participated. But, this year, the outfit’s deep-learning network was head-and-shoulders above other teams and, say scientists, performed so mind-bogglingly well that it could herald a revolution in biology.

“It’s a game changer,” says Andrei Lupas, an evolutionary biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen, Germany, who assessed the performance of different teams in CASP. AlphaFold has already helped him find the structure of a protein that has vexed his lab for a decade, and he expects it will alter how he works and the questions he tackles. “This will change medicine. It will change research. It will change bioengineering. It will change everything,” Lupas adds.

In some cases, AlphaFold’s structure predictions were indistinguishable from those determined using ‘gold standard’ experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography and, in recent years, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). AlphaFold might not obviate the need for these laborious and expensive methods — yet — say scientists, but the AI will make it possible to study living things in new ways.

The structure problem

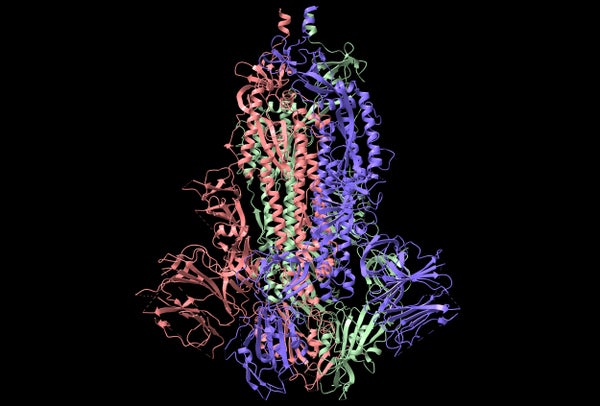

Proteins are the building blocks of life, responsible for most of what happens inside cells. How a protein works and what it does is determined by its 3D shape — ‘structure is function’ is an axiom of molecular biology. Proteins tend to adopt their shape without help, guided only by the laws of physics.

For decades, laboratory experiments have been the main way to get good protein structures. The first complete structures of proteins were determined, starting in the 1950s, using a technique in which X-ray beams are fired at crystallized proteins and the diffracted light translated into a protein’s atomic coordinates. X-ray crystallography has produced the lion’s share of protein structures. But, over the past decade, cryo-EM has become the favoured tool of many structural-biology labs.

Scientists have long wondered how a protein’s constituent parts — a string of different amino acids — map out the many twists and folds of its eventual shape. Early attempts to use computers to predict protein structures in the 1980s and 1990s performed poorly, say researchers. Lofty claims for methods in published papers tended to disintegrate when other scientists applied them to other proteins.

Moult started CASP to bring more rigour to these efforts. The event challenges teams to predict the structures of proteins that have been solved using experimental methods, but for which the structures have not been made public. Moult credits the experiment — he doesn’t call it a competition — with vastly improving the field, by calling time on overhyped claims. “You’re really finding out what looks promising, what works, and what you should walk away from,” he says.

DeepMind’s 2018 performance at CASP13 startled many scientists in the field, which has long been the bastion of small academic groups. But its approach was broadly similar to those of other teams that were applying AI, says Jinbo Xu, a computational biologist at the University of Chicago, Illinois.

The first iteration of AlphaFold applied the AI method known as deep learning to structural and genetic data to predict the distance between pairs of amino acids in a protein. In a second step that does not invoke AI, AlphaFold uses this information to come up with a ‘consensus’ model of what the protein should look like, says John Jumper at DeepMind, who is leading the project.

The team tried to build on that approach but eventually hit the wall. So it changed tack, says Jumper, and developed an AI network that incorporated additional information about the physical and geometric constraints that determine how a protein folds. They also set it a more difficult, task: instead of predicting relationships between amino acids, the network predicts the final structure of a target protein sequence. “It’s a more complex system by quite a bit,” Jumper says.

Startling accuracy

CASP takes place over several months. Target proteins or portions of proteins called domains — about 100 in total — are released on a regular basis and teams have several weeks to submit their structure predictions. A team of independent scientists then assesses the predictions using metrics that gauge how similar a predicted protein is to the experimentally determined structure. The assessors don’t know who is making a prediction.

AlphaFold’s predictions arrived under the name ‘group 427’, but the startling accuracy of many of its entries made them stand out, says Lupas. “I had guessed it was AlphaFold. Most people had,” he says.

Some predictions were better than others, but nearly two-thirds were comparable in quality to experimental structures. In some cases, says Moult, it was not clear whether the discrepancy between AlphaFold’s predictions and the experimental result was a prediction error or an artefact of the experiment.

AlphaFold’s predictions were poor matches to experimental structures determined by a technique called nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, but this could be down to how the raw data is converted into a model, says Moult. The network also struggles to model individual structures in protein complexes, or groups, whereby interactions with other proteins distort their shapes.

Overall, teams predicted structures more accurately this year, compared with the last CASP, but much of the progress can be attributed to AlphaFold, says Moult. On protein targets considered to be moderately difficult, the best performances of other teams typically scored 75 on a 100-point scale of prediction accuracy, whereas AlphaFold scored around 90 on the same targets, says Moult.

About half of the teams mentioned ‘deep learning’ in the abstract summarizing their approach, Moult says, suggesting that AI is making a broad impact on the field. Most of these were from academic teams, but Microsoft and the Chinese technology company Tencent also entered CASP14.

Mohammed AlQuraishi, a computational biologist at Columbia University in New York City and a CASP participant, is eager to dig into the details of AlphaFold’s performance at the contest, and learn more about how the system works when the DeepMind team presents its approach on 1 December. It’s possible — but unlikely, he says — that an easier-than-usual crop of protein targets contributed to the performance. AlQuraishi’s strong hunch is that AlphaFold will be transformational.

“I think it’s fair to say this will be very disruptive to the protein-structure-prediction field. I suspect many will leave the field as the core problem has arguably been solved,” he says. “It’s a breakthrough of the first order, certainly one of the most significant scientific results of my lifetime.”

Faster structures

An AlphaFold prediction helped to determine the structure of a bacterial protein that Lupas’s lab has been trying to crack for years. Lupas’s team had previously collected raw X-ray diffraction data, but transforming these Rorschach-like patterns into a structure requires some information about the shape of the protein. Tricks for getting this information, as well as other prediction tools, had failed. “The model from group 427 gave us our structure in half an hour, after we had spent a decade trying everything,” Lupas says.

Demis Hassabis, DeepMind’s co-founder and chief executive, says that the company plans to make AlphaFold useful so other scientists can employ it. (It previously published enough details about the first version of AlphaFold for other scientists to replicate the approach.) It can take AlphaFold days to come up with a predicted structure, which includes estimates on the reliability of different regions of the protein. “We’re just starting to understand what biologists would want,” adds Hassabis, who sees drug discovery and protein design as potential applications.

In early 2020, the company released predictions of the structures of a handful of SARS-CoV-2 proteins that hadn’t yet been determined experimentally. DeepMind’s predictions for a protein called Orf3a ended up being very similar to one later determined through cryo-EM, says Stephen Brohawn, a molecular neurobiologist at the University of California, Berkeley, whose team released the structure in June. “What they have been able to do is very impressive,” he adds.

Real-world impact

AlphaFold is unlikely to shutter labs, such as Brohawn’s, that use experimental methods to solve protein structures. But it could mean that lower-quality and easier-to-collect experimental data would be all that’s needed to get a good structure. Some applications, such as the evolutionary analysis of proteins, are set to flourish because the tsunami of available genomic data might now be reliably translated into structures. “This is going to empower a new generation of molecular biologists to ask more advanced questions,” says Lupas. “It’s going to require more thinking and less pipetting.”

“This is a problem that I was beginning to think would not get solved in my lifetime,” says Janet Thornton, a structural biologist at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory-European Bioinformatics Institute in Hinxton, UK, and a past CASP assessor. She hopes the approach could help to illuminate the function of the thousands of unsolved proteins in the human genome, and make sense of disease-causing gene variations that differ between people.

AlphaFold’s performance also marks a turning point for DeepMind. The company is best known for wielding AI to master games such Go, but its long-term goal is to develop programs capable of achieving broad, human-like intelligence. Tackling grand scientific challenges, such as protein-structure prediction, is one of the most important applications its AI can make, Hassabis says. “I do think it’s the most significant thing we’ve done, in terms of real-world impact.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on November 30 2020.