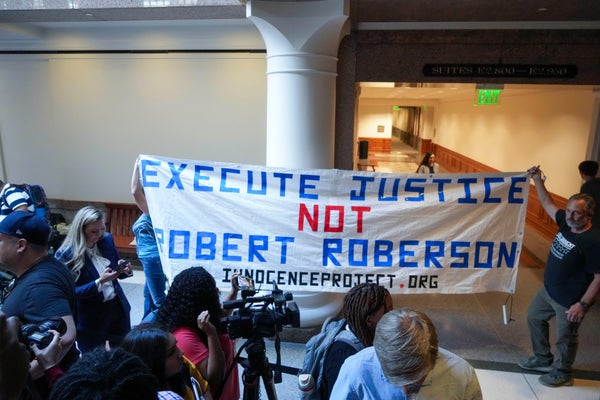

In a last-minute effort to save the life of a man on death row, a bipartisan group of Texas legislators has just done something extraordinary: they have unanimously subpoenaed Robert Roberson, convicted in 2003 of killing his daughter based on the now-discredited theory of shaken baby syndrome, to testify before them five days after he was scheduled to be executed, effectively forcing the state to keep him alive.

Roberson is one of many people who have been imprisoned for injuries to a child that prosecutors argue resulted from violent shaking. But research has exposed serious flaws in these determinations, and dozens of other defendants who have been wrongly convicted under this theory have been exonerated. Yet Roberson remains on death row, even as politicians, scientists and others—including the lead detective who investigated him and one of the jurors who convicted him—have spoken out on his behalf. If his execution proceeds, they and many others believe that Texas will be killing an innocent man for a “crime” that never happened.

As our scientific understanding of shaken baby syndrome has evolved over the past 20 years, justice requires that courts reexamine old convictions in light of new findings. This is especially true for Roberson, who would be the first person in the U.S. to be executed for a conviction based on shaken baby syndrome. No matter one’s view of the death penalty, the ultimate punishment must be held to the ultimate standard of proof—and Roberson’s case falls woefully short of that standard.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The theory behind shaken baby syndrome dates back to the early 1970s, when two medical researchers—Norman Guthkelch and John Caffey—separately published the first scientific papers explaining that shaking an infant can cause fatal internal injuries even absent external injuries. Over time physicians and law enforcement officers, among others, widely began to rely on a triad of symptoms—brain bleeding, brain swelling and retinal bleeding—as definitive proof that someone had abused a child by shaking. To support this theory, researchers cited cases in which a child displayed these symptoms and a caretaker confessed to shaking the child, which ostensibly confirmed the triad as a reliable way to diagnose abuse.

There is no doubt that shaking a child can cause injuries, including those that comprise the shaken baby syndrome triad. Newer research, however, has shown that shaking is not the only way to cause those injuries: They can also result from an accidental “short fall” (e.g., falling off a bed) as well as from other medical causes (e.g., pneumonia, improper medication)—all of which were true of Roberson’s daughter. In fact, a 2024 study found that the injuries historically used to diagnose shaking are actually more likely to result from accidents than from shaking. In short, modern science understands that the presence of these symptoms does not necessarily mean that a child was abused, nor does their absence mean that they were not abused.

Why did clinicians wrongly trust this triad of symptoms for so long? The short answer is that correcting misconceptions requires a feedback loop that is often lacking in child abuse investigations. When a doctor diagnoses a living adult and prescribes a treatment, the effectiveness of that treatment provides feedback on the correctness of their diagnosis; if the treatment proves ineffective, doctors can learn from this misdiagnosis and adjust future diagnoses accordingly. Such feedback, however, is not always sufficient; for instance, doctors practiced bloodletting for centuries because it was generally accepted and seemed to work for some patients, though it was an illusory correlation. With respect to shaking, doctors rarely learn whether a child was actually shaken because the child is typically deceased or unable to articulate what happened, and thus doctors rarely receive feedback that the triad led to an incorrect diagnosis.

As for the studies that used a caretaker’s confession to establish that abuse occurred, it is now well-known that innocent people sometimes confess to crimes they did not commit, such that confessions are not synonymous with truth. Some scholars have even argued that the unique circumstances of suspected shaking cases (e.g., suspects’ emotional state) create an especially high risk of false confession.

Further complicating matters, child abuse determinations are subject to cognitive bias, in which extraneous information leads experts to interpret the same injury in different ways—at least one of which must be incorrect. In one study, for example, medical professionals more often judged the same childhood injury as abuse rather than an accident if told that the child’s parents were unmarried or drug users—both of which appear to be true of Roberson. Another study found that those same extraneous factors led emergency room doctors to misdiagnose accidental injuries as abuse in a staggering 83 percent of cases.

Even merely knowing about a criminal accusation can affect how a doctor appraises a child’s injuries. In one study, independent experts reviewed medical records from cases where, unbeknownst to them, a fellow expert had testified that the child was shaken. In 94 percent of those cases, the independent experts concluded that the child’s “head injuries… possibly, or even probably, had a non-traumatic cause.”

Autopsy decisions are likewise unreliable. In a 2021 study, medical examiners’ opinions of whether a child’s death was an accident or homicide were heavily swayed by the child’s race and who brought them to the hospital, even though the child’s injuries and history were otherwise identical. In response, prominent medical examiners explained that manner of death is “not a ‘scientific’ determination” and “often does not fit well in court.” Yet jurors—including some from at Roberson’s trial—often hear and trust these tenuous opinions, which has led some scholars to argue that manner of death testimony should not be admissible in U.S. courts, as is the case in nearly every other country.

As research debunking shaken baby syndrome has grown, so too have successful legal challenges to criminal convictions that hinge on it, including another Texas case where—just eight days before Roberson’s scheduled execution—a man was granted a new trial on the grounds that “scientific knowledge has evolved” since his 2004 trial and “would likely yield an acquittal” in 2024. Before his 2016 death, even Guthkelch—one of the architects of the theory—lamented that his “friendly suggestion for avoiding injury to children has become an excuse for imprisoning innocent parents.” Roberson is one of those innocent parents.

Science is constantly evolving, and when it reveals a past mistake, we do not simply resign ourselves to it; we take corrective action. Our legal system should be no different. When Robert Roberson was convicted, the injury triad was widely accepted as proof of shaking—but as science has progressed, that is no longer the case. The law’s guarantee of due process must account for such progress, especially when a person’s life literally depends on it. For the law to ignore evolving scientific knowledge is not merely unfair; it is criminal.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.