Humans must have learned to sing early in our history because “we can find something we can call music in every society,” says musicologist Yuto Ozaki of Keio University in Tokyo. But did singing evolve as a mere by-product of speaking or with its own unique role in human society? To investigate this question, Ozaki and a large team of collaborators compared samples of songs and speech from around the world. These categories can vary wildly across cultures: songs can be lilting lullabies or rhythmic chants or wailing laments, and some spoken languages have more “musical” qualities, such as tonal languages, which convey meaning through pitch.

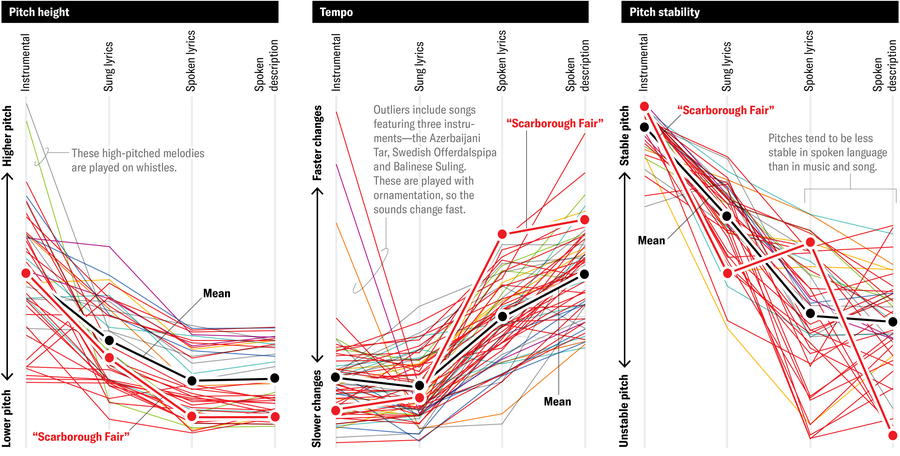

Despite this variation, the researchers found three worldwide trends: songs tend to be slower than speech, with higher and slightly more stable pitches. These consistent differences suggest that singing isn’t just a by-product of speech, yet why it evolved is still unknown. Perhaps it developed to unite people, an idea called the social-bonding hypothesis, says co-author Patrick Savage, a musicologist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. “Slower, more regular and more predictable melodies may allow us to synchronize and to harmonize,” he says, “and through that, to bring us together in a way that language can’t.”

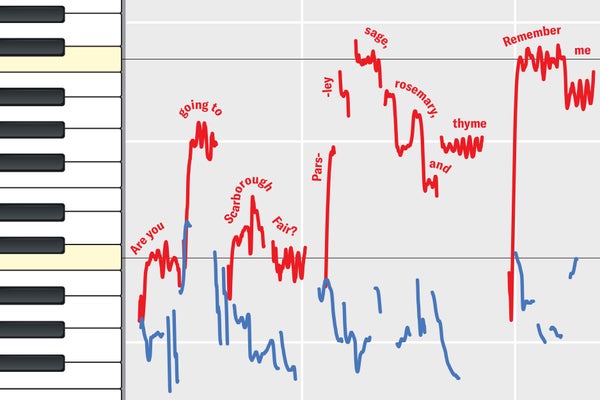

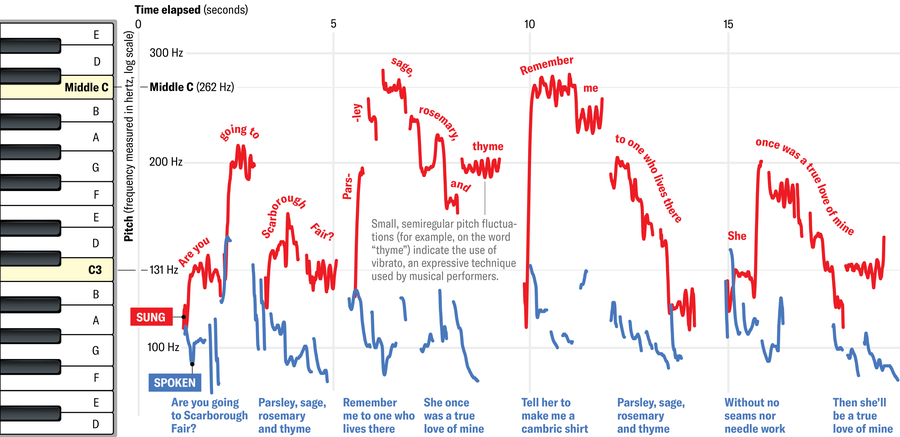

Breaking Down a Song

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The chart visualizes two recordings of the English folk song “Scarborough Fair”—one sung, one spoken—by Patrick Savage, a study author and participant. The song unfolds at around half the speed of the spoken version, and its pitches are generally higher. They are also more stable, being centered on fixed musical notes, but with added expressive pitch fluctuations such as scoops and vibrato. In contrast, the spoken performance never settles on a pitch for long.

Duncan Geere and Miriam Quick from Loud Numbers

Different Songs, Similar Patterns

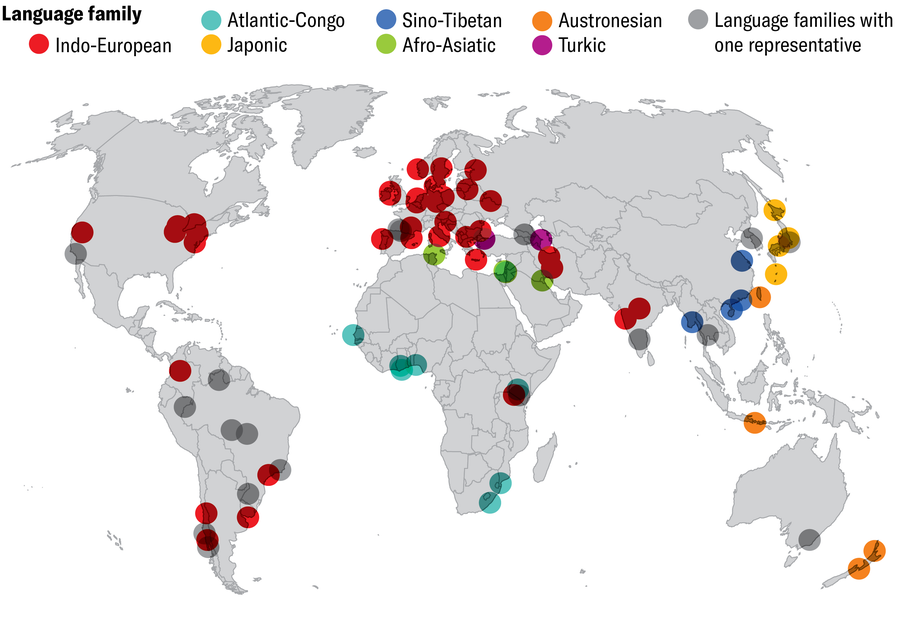

The researchers analyzed 300 audio recordings by 75 collaborators speaking 55 languages. Each person sang a traditional song, recited its lyrics, played an instrumental version of its melody, then described its meaning. The authors showed how pitch height, tempo and pitch stability vary as a person moves from instrumental music to singing to speech, and they found commonalities across cultures.

Duncan Geere and Miriam Quick from Loud Numbers; Source: “Globally, Songs and Instrumental Melodies Are Slower and Higher and Use More Stable Pitches than Speech: A Registered Report,” by Yuto Ozaki et al., in Science Advances, Vol. 10; May 15, 2024 (data)