Pickleball has been the fastest-growing sport in the U.S. for four years running. More than 13.6 million people now play, according to one trade association. Towns, schools and sports clubs are building courts everywhere, and people of all ages and abilities are flocking to them.

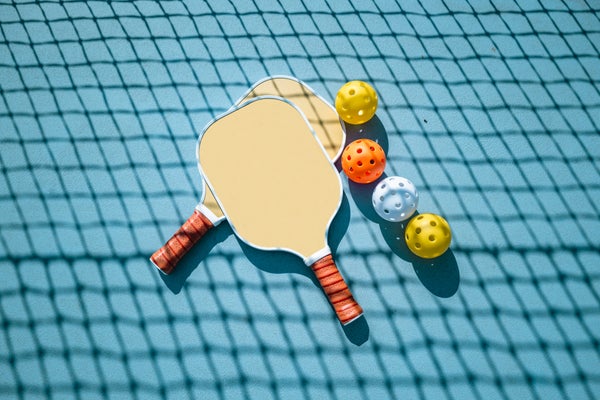

If you haven’t played or seen pickleball, imagine a tennis court and net but downsized. And instead of rackets, players use shorter, solid paddles. At the center of the craze is the ball, a bit larger than a tennis ball, which is often bright yellow and resembles a Wiffle ball—a hard plastic ball with small holes in it. A pickleball can rocket between opposing players who are drilling it at each other from only 14 feet away, or it can float for what seems like an eternity when it is lobbed skyward. The “pop!” the ball makes when it is struck hard by a paddle is so loud and distinctive that it can be heard a block away if the neighborhood is quiet, and yet the sound is muffled when a player taps a really soft “dink” shot (my personal favorite when I’m playing) over the net.

The truths and myths that abound about the balls, paddles and shots come down to physics, of course. Scientific American found an expert who has gone to extremes to investigate: Phil Hipol, an acoustics and structural dynamics engineer who has worked in the aerospace, semiconductor and building industries and is a licensed professional engineer in Florida, the global epicenter of pickleball fanaticism. I’m going to call him Professor Pickleball. Of course, he’s also an avid player. You can find his insights below. And if you really want to dive into the abyss, go to his blog, Pickleball Science, where you’ll find experiments, equations and some incredible homemade rigs he’s created to test all things pickleball.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The following text is summarized from my interview with Hipol, with occasional details from his blog, which he has given permission to use.

How fast does the ball fly?

According to Professor Pickleball’s calculations, the fastest serve that will just clear the net and not fly past the opposite baseline leaves the paddle at 54 miles per hour. But if the server applies a lot of topspin (say, 1,200 revolutions per minute, or rpm), this will make the ball dive down harder once it crosses the net, and it can leap off the paddle at up to 65 mph. At that speed, the ball takes just 0.64 second to leave the server and hit the opposite far end of the court. The holes create turbulence—much like dimples on a golf ball or seams on a baseball do—which controls the trajectory. At that speed and spin, “you can hear the ball whizzing toward you,” Hipol says.

The fastest action happens when players approach the net and start striking line drives at each other. When players are 14 feet apart, a ball traveling 45 mph gives them only about 0.2 second to react, according to Hipol. That’s pushing the limit of conscious human reaction time. (Reflexes can be as fast as 0.08 second, but those signals do not have to go to the brain.)

RichLegg/Getty Images

How long can the ball hang in the air?

At the opposite extreme is a shot called a lob. When a player lobs the ball, they launch it almost straight up, so it arcs high over the net and drops almost straight down near the opposite end line, which can be a difficult shot to return. Professor Pickleball says if a player “hits the ball from the baseline with an upward angle of 55 degrees and initial speed of 40 mph, with 1,200 rpm of topspin, it will reach a height of almost 20 feet and will take four seconds to drop.” In this case, air flowing over the holes indirectly sustains loft.

How loud is the pop of a pickleball on a paddle?

Pickleballs make a unique “pop” when a paddle hits them hard and more of a “plunk” when a paddle hits them softly. Professor Pickleball—remember, he’s an acoustics engineer—says the impact at the face of a hard racket can be as loud as 120 decibels (dB), which registers at about 80 dB for a player on the other side of the net. For comparison, 120 dB is the loudness of a hammer striking a nail or a passing ambulance siren; 80 dB equates to heavy traffic or a noisy restaurant. Many players wear safety glasses; maybe they should consider earplugs!

How can the sound be so loud? Hipol says that in this case, “it’s not the ball; it’s the paddle.” Most paddles have a hard surface layer, and a paddle’s short duration of impact with the ball—on the order of only four milliseconds—causes it to vibrate like the skin of a drum. The interiors of most paddles are a honeycomb of fibers and air, providing a hollowness that amplifies the sound like the inside of a drum.

Complaints about noise from people who live near pickleball courts are starting to rise in more and more towns, so some manufacturers have begun to market “quiet” paddles, which Hipol says may include some amount of a foamy substance inside to absorb some of the sound waves. Whether players will like the power and control of quiet paddles remains to be seen.