The globe hums with thousands of languages. But when did humans first lay out a structured system to communicate, one that was distinct to a particular area?

Scientists are aware of more than 7,100 languages in use today. Nearly 40 percent of them are considered endangered, meaning they have a declining number of speakers and are at risk of dying out. Some languages are spoken by fewer than 1,000 people, while more than half of the world’s population uses one of just 23 tongues.

These languages and dead ones that are no longer spoken weave together millennia of human interactions. That means the task of determining the world’s oldest language is more than a linguistic curiosity. For instance, in order to decipher clay tablet inscriptions or trace the evolution of living tongues, linguists must grapple with questions that extend beyond language. In doing so, their research reveals some of the secrets of ancient civilizations and even sparks debates that blend science and culture.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Ancient languages, just like contemporary languages, are crucial for understanding the past. We can trace the history of human migrations and contacts through languages. And in some cases, the language information is our only reliable source of information about the past,” says Claire Bowern, a Professor of Linguistics at Yale University. “The words that we can trace back through time give us a picture of the culture of past societies.”

Language comes in different forms—including speech, gestures and writing—which don’t all leave conclusive evidence behind. And experts use different approaches to determine a language’s age.

Tracing the oldest language is “a deceptively complicated task,” says Danny Hieber, a linguist who studies endangered languages. One way to identify a language’s origins is to find the point at which a single tongue with different dialects became two entirely distinct languages, such that people speaking those dialects could no longer understand each other. “For example, how far back in history would you need to go for English speakers to understand German speakers?” he says. That point in time would mark the origins of English and German as distinct languages, branching off from a common proto-Germanic language.

Alternatively, if we assume that most languages can be traced back to an original, universal human language, all languages are equally old. “You know that your parents spoke a language, and their parents spoke a language, and so forth. So intuitively, you’d imagine that all languages were born from a single origin,” Hieber says.

But it’s impossible to prove the existence of a proto-human language—the hypothetical direct ancestor of every language in the world. Accordingly, some linguists argue that the designation of the “oldest language” should belong to one with a well-established written record.

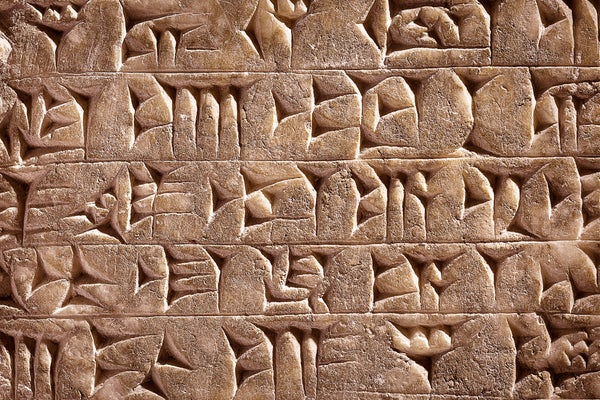

Many of the earliest documented examples of writing come from languages that used cuneiform script, which featured wedge-shaped characters impressed into clay tablets. Among these languages are Sumerian and Akkadian, both dating back at least 4,600 years. Archaeologists have also found Egyptian hieroglyphs carved into the tomb of Pharaoh Seth-Peribsen that date to around the same historical period. The inscription translates to: “He has united the Two Lands for his son, Dual King Peribsen,” and it is considered the earliest-known complete sentence.

Historians and linguists generally agree that Sumerian, Akkadian and Egyptian are the oldest languages with a clear written record. All three are extinct, meaning they are no longer used and do not have any living descendants that can carry the language to the next generation.

As for the oldest language that is still spoken, several contenders emerge. Hebrew and Arabic stand out among such languages for having timelines that linguists can reasonably trace, according to Hieber. Although the earliest written evidence of these languages dates back only around 3,000 years, Hieber says that both belong to the Afroasiatic language family, whose roots trace back to 18,000 to 8,000 B.C.E., or about 20,000 to 10,000 years ago. Even with this broad time frame, contemporary linguists widely accept Afroasiatic as the oldest language family. But the exact point at which Hebrew and Arabic diverged from other Afroasiatic languages is heavily disputed.

Bowern adds Chinese to the list of candidates. The language likely emerged from Proto-Sino-Tibetan, which is also an ancestor to Burmese and the Tibetan languages, around 4,500 years ago, although the exact date is disputed. The earliest documented evidence of the Chinese writing system comes from inscriptions on tortoise shells and animal bones that date back to about 3,300 years ago. Modern Chinese characters weren’t introduced until centuries later, however.

Turn the clock back an additional one or two millennia, and the linguistic record becomes especially murky. Deven Patel, a professor of South Asia studies at the University of Pennsylvania, says the earliest written records of Sanskrit are ancient Hindu texts that were composed between 1500 and 1200 B.C.E. and are part of the Vedas, a collection of religious works from ancient India. “In my view, Sanskrit is the oldest continuous language tradition, meaning it’s still producing literature and people speak it, although it’s not a first language in the modern era,” Patel says.

Some linguists, however, argue that the appearance of Sanskrit was predated by Tamil, a Dravidian language that is still used by almost 85 million native speakers in southern India and Sri Lanka. Scientists have documented Tamil for at least 2,000 years. But scholars have contested the true age of the oldest surviving work of Tamil literature, known as the Tolkāppiyam, with estimates ranging from 7,000 to 2,800 years. “There are disputes among scholars about the precise date of ancient texts ascribed to Tamil and whether the language used is actually similar enough to modern Tamil to categorize them as the same language,” Patel says. “Tamil [speakers] have been especially [enthusiastic] in trying to separate the language as uniquely ancient.”

Disagreements about the age of Sanskrit and Tamil illustrate the broader issues in pinpointing the world’s oldest language. “To answer this question, we’ve seen people create new histories, which are as much political as they are scientific,” Patel says. “There are bragging rights associated with being the oldest and still evolving language.”