The combination of mifepristone and misoprostol, the two-drug regimen that is usually prescribed to terminate a pregnancy, is extremely safe and effective — even when the medication abortion is provided over a remote telehealth connection, a new study shows. In a survey of more than 6,000 remote medication abortions between April 2021 and January 2022, only 0.25 percent of patients experienced adverse outcomes such as excessive bleeding or infection. Less than 2.5 percent experienced a continued pregnancy. Published on February 15 in Nature Medicine, the study research is the largest study of at-home telehealth abortion to date.

“The study finds that providing telehealth care is just as safe and effective as providing abortion care in person,” says Ushma Upadhyay, a quantitative public health scientist at the University of California, San Francisco, and the paper’s lead author. In addition to synchronous abortion care, in which a patient communicated with a health professional over the phone or a video chat, Upadhyay’s team evaluated asynchronous care, in which the patient and provider did not interact in real time. The researchers found that both approaches had equally successful outcomes.

“Providing the option of asynchronous care really helps improve access,” says Kelly Cleland, executive director of the American Society for Emergency Contraception, who was not involved in the study. For example, receiving abortion care via secure text messaging might be the best option for people who live in a rural area with limited Wi-Fi access or who could face threats of violence from intimate partners. The new study supports this as a safe and effective option, Cleland says.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Medication abortion accounts for more than half of all abortions in the US, according to a 2022 survey from the Guttmacher Institute. It is a vital form of health care for people who live in an area without easy access to an abortion clinic or where abortion is illegal. Most experts predict that the percentage of medication abortions in the U.S. will only increase in coming years, as COVID waves continue to surge and care options becomes increasingly restricted in many parts of the country.

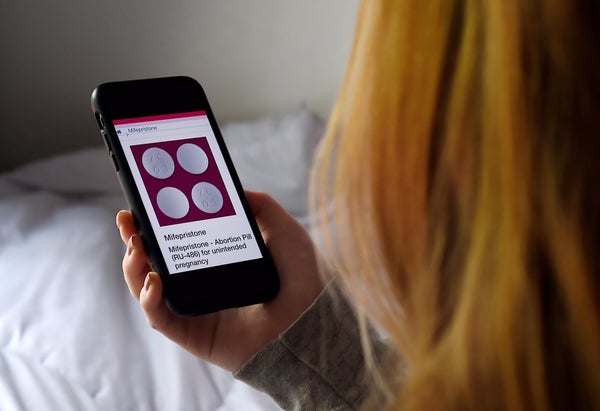

Most medication abortions are administered by first using 200 milligrams of mifepristone—which blocks the release of the hormone progesterone—followed by up to 1,600 micrograms of misoprostol, which causes the uterus to empty. Despite more than 20 years of data attesting to their safety, both drugs and especially mifepristone—have repeatedly been subject to scrutiny and regulatory challenges. This trend has not slowed in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade.

“This is really important and timely evidence,” says Silpa Srinivasulu, a public health researcher at the Reproductive Health Access Network, who was not involved in the research. The new study comes just weeks before the Supreme Court is scheduled to hear a case that could jeopardize mifepristone’s Food and Drug Administration approval and effectively ban its use.

Under current guidelines, mifepristone should be prescribed by a certified health care provider to patients 10 weeks or less into a pregnancy. The agency expanded the drug’s approval in 2021 to include telehealth prescriptions—a provision that helped thousands of Americans stay safe during the height of the COVID pandemic. Soon afterward, however, antiabortion advocates filed a lawsuit that has challenged not only the updated guidelines but also mifepristone’s initial FDA approval in 2000.

Many health care providers have pointed out that the scientific basis of the current lawsuit is flimsy at best and nonexistent at worst. In fact, two key papers cited by the plaintiffs in the suit as evidence of mifepristone’s potential for harm were recently retracted. “These obstacles are politically motivated attacks,” Srinivasulu says. “They’re not grounded in science.”

Health care experts also worry that the case could undermine the FDA’s ability to evaluate other drugs. A decision in favor of a small group of doctors “with an axe to grind against abortion” might call into question the agency’s authority to regulate everything from cancer treatments to Tylenol, Cleland says. “It’s wild.”

But the new research clearly demonstrates that “the FDA followed the science when it expanded how medication abortion can be provided,” Upadhyay says. She hopes that the Supreme Court will do the same in its upcoming decision.