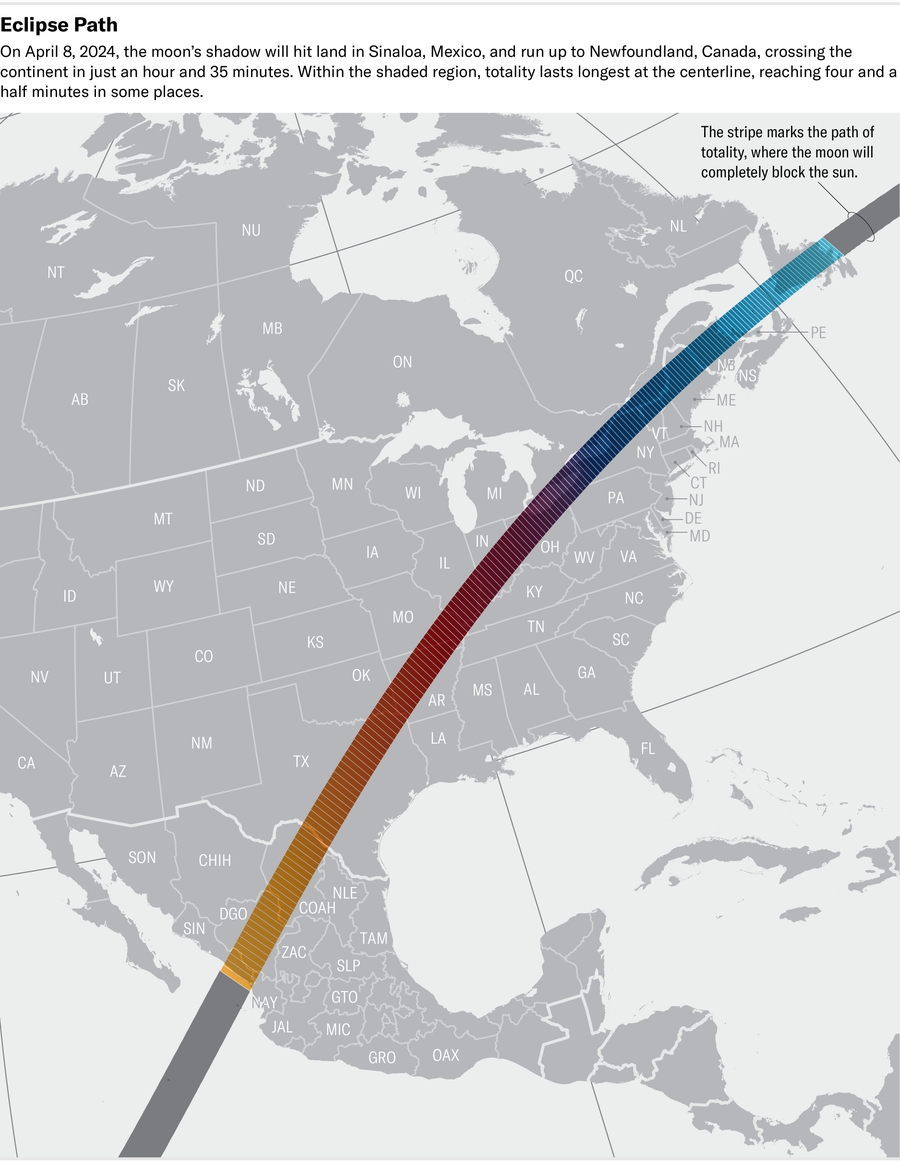

This article is part of a special report on the total solar eclipse that will be visible from parts of the U.S., Mexico and Canada on April 8, 2024.

During an eclipse, as the moon slowly begins to veil the sun, crescent-shaped shadows appear on the ground, and the world drops into an eerie daytime twilight. On Monday, this will happen across a large swath of North America.

How did ancient cultures respond to the darkness shrouding the light? In the past few decades, a scientific field called archeoastronomy has emerged to investigate questions such as this. Although it’s a challenge to know what earlier humans saw when they stood in the shadow of an eclipse—especially the further back we go—archeoastronomers have used clues ranging from bark books to petroglyphs to ancient Chinese oracle bones to piece together these bygone stories of the cosmos.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The “Six-Five Beat”

Humans have been calculating the recurrence of solar eclipses for thousands of years. Many ancient cultures predicted these events mathematically using what Anthony Aveni, a pioneer of archeoastronomy and professor emeritus at Colgate University, calls the “six-five beat.” Solar and lunar eclipses usually recur every six lunar months or, more rarely, every five lunar months. Over time, by observing and calculating these intervals, the ancient Maya, Chinese and Babylonians all homed in on two predictable patterns for when identical solar and lunar eclipses would recur: one pattern spans 41 months, the other 47. Here’s how these patterns, denoted as “A” and “B”, come about:

A. The 41-month pattern: 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 5 = 41 months, or some 3.4 years, after a total or near-total eclipse, an almost identical eclipse occurs.

Or:

B. The 47-month pattern: 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 5 = 47 months, or some 3.9 years, after a total or near-total eclipse, an almost identical eclipse occurs.

Then, after more time, these cultures found even more patterns. The Babylonians, for instance, noticed that after A + A + B + B + B, or 223 months (18.5 years), another identical sequence of eclipses occurred, called the Saros cycle. All these patterns, governed by the laws of planetary motion, were made by simply observing the sky with the naked eye—so it’s possible, or even likely, that these Maya, Chinese and Babylonian cultures had been using the six-five beat to predict eclipses even in prehistoric times, before written records. “I have no doubt that people could do this a few thousand years [prior] and then pass that information on orally,” Aveni says.

Cairn Carvings

The oldest surviving depiction of an eclipse might be one from Loughcrew Megalithic Cemetery, also known as the Hills of the Witch, near Oldcastle, Ireland. This site’s Neolithic passage tombs, marked by large cairns, were built in the fourth millennium B.C.E.—making them nearly a millennium older than Stonehenge.

Examining one of the cairns in 1999, archaeoastronomer Paul Griffin discovered a stone carving of overlapping concentric circles that he thought may depict an eclipse. He found that a near-total eclipse occurred at Loughcrew on November 30, 3340 B.C.E., around the time the cairns were built; this makes it plausible that the carving, called a petroglyph, did indeed represent an eclipse. But such a thing can’t be proven, and Aveni says the concentric circles could have any number of possible meanings.

Dragon Bones and Oracle Bones

A few millennia later, the oldest verifiable solar eclipse records were carved in Anyang, China. This city, then called Yin, was the capital of the ancient Shang dynasty (1600–1045 B.C.E.)—the first Chinese period that left behind written records. This legacy was rediscovered relatively recently, in 1899, when an Anyang pharmacist gave antiquarian and philologist Wang Yirong a prescription for a traditional remedy made by grinding up “dragon bones.” Wang was about to grind the bones when he noticed that they were adorned with ancient Chinese inscriptions. These weren’t dragon bones but oracle bones: oxen shoulder blades and tortoise shells once used to predict the future. Eventually the artifacts were traced to a site near Anyang where some 50,000 inscribed oracle bones dating from 1400 to 1200 B.C.E. have since been discovered.

“Divination played an enormously important role at the time,” says Xueshun Liu, a Chinese language lecturer in the Department of Asian Studies at the University of British Columbia. These bone inscriptions are the oldest known Chinese-language documents—and they include descriptions of eclipses. During the Shang dynasty, when an eclipse loomed, specially marked oracle bones were placed over a fire; heating caused small cracks that were believed to be messages from deceased ancestors. A diviner, or oracle, then interpreted the cracks and inscribed prophecies on the bones.

One of the many oracle bones that mentions an eclipse says: “The king, reading the crack, said: ‘There will be harm.’ Another simply read, “The sun has been eaten.”

A Dark, Belching Sun

Any given place on Earth’s surface will only experience one total solar eclipse, lasting only a few minutes, every 375 years on average. So it’s even rarer for this to coincide with another solar event called a coronal mass ejection, or CME. These occur when giant bubbles of plasma and magnetic field burst from the sun’s corona, or its outer atmosphere. These ejections could be visible to the naked eye during a total solar eclipse, with the moon shielding everything but the sun’s corona.

“CMEs are not that rare. We get several of them during the day, especially during solar maximum,” or the peak of the sun’s 11-year activity cycle, says C. Alex Young, associate director for science in the Heliophysics Science Division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. But he notes that the odds of one coinciding with “four or so minutes of an eclipse are slim.”

It’s possible, however, that the ancient Pueblo people of Chaco Canyon, a city that thrived from C.E. 850–1250, may have witnessed such a spectacle. Evidence comes from Piedra del Sol, or “Rock of the Sun,” a large boulder in modern-day New Mexico inscribed with numerous previously identified Chaco astronomical markers. In 1992 solar astronomer Kim Malville was helping lead a three-week field trip for college students when he “noticed a peculiar petroglyph” on the boulder. It looked like the sun was belching out rays. What’s more, “there was a pecked mark where [Venus] would have been,” says Malville, a professor emeritus of astrophysical and planetary sciences at the University of Colorado. Venus can be visible during an eclipse.

After referencing a list of historic eclipses, Malville discovered that only one total solar eclipse—that of June 29, 1097—occurred at the peak of Chacoan culture. A few years later, solar physicists confirmed that the 1097 eclipse occurred during a period of high solar activity, making the tandem appearance of an eclipse and a CME likelier.

Credit: Katie Peek; Source: NASA (eclipse track data)

This year on April 8, eclipse watchers in North America will have similarly elevated chances of seeing a CME because the sun is currently at the peak of its activity—and is belching out plasma multiple times per day. “While the chances of seeing a coronal mass ejection coincide with an eclipse are rare, the chances are much higher right now,” Young says. “I’ve studied these things for 20 years, and the idea of seeing this from the ground, with my own eyes—well, that would really be quite a sight.”

Look Outside the Lens

As we try to understand how the peoples of the past experienced the world, it’s important to look around the lens of our modern and often Western-dominated culture, says Aveni, who began his career as an astronomer and then moved to studying the cosmos through anthropology and Native American studies.

“We must be very careful about treating all cultures that came before us as capital-O ‘Other,’” Aveni says. “They traveled a totally different road from Western eclipse science. Sometimes our questions can be misguided. Did they know the Earth was round? Did they know about the galaxy?” Those aren’t the right questions to ask, he says. “They didn’t live in our world.”

And we don’t live in theirs. With our ultraprecise clocks and compasses, we can often choose to forget the sky altogether—something unthinkable for many peoples of the past. “When it comes down to it, other cultures didn’t do things the way we do them,” Aveni says. “And that’s what makes studying them so fascinating.”