Teenagers are some of the most sleep-deprived people in the U.S. On average, teens do not get enough sleep, and more important, they do not get enough quality sleep, according to researchers. We could blame cell phones and other light-emitting technologies for keeping kids awake at night, but late nights are just part of the equation. In addition to technology, one fairly indisputable factor contributes to this collective sleepiness: school start times.

Over decades researchers have amassed evidence showing that pushing back the first bell of middle and high school would benefit the physical, mental and emotional health of older children, not to mention their academic performance. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with several medical societies, has endorsed later start times. Some school districts, as well as the state of California, have already shown respect for that evidence with new start times.

Yet far too many school districts are reluctant to make the change, whether for logistical, financial or cultural reasons. This is unfair to teens. A generation of students is playing catchup from COVID, and we need to prioritize their health and wellness by pushing back the start of the school day. Honoring their biological and social needs will create more resilient adults who can thrive in a world filled with current complexities and future ones we can't begin to predict.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Teenagers need about nine hours of sleep a night—but they get closer to seven. And around puberty, their circadian clocks shift by a couple of hours, meaning they get tired later at night than before and wake up later in the morning than they used to. This shift reverses at adulthood. The biological nature of this daily rhythm means that sending a teenager to bed earlier won't necessarily mean they fall asleep earlier.

Experts tell us that teens are missing out on both restorative sleep and REM sleep, especially the cycles that normally happen just before a person wakes up. Restorative sleep helps to repair the body after a hard day, and it may improve immune function and other biological processes. REM sleep solidifies events and learning into memories. So when a 10th grader who naturally goes to bed around 11 P.M. has to wake up at 6 A.M. for school, that teen is losing not only hours of sleep but hours of quality sleep. And even if they sleep in on the weekends, they won't fully catch up.

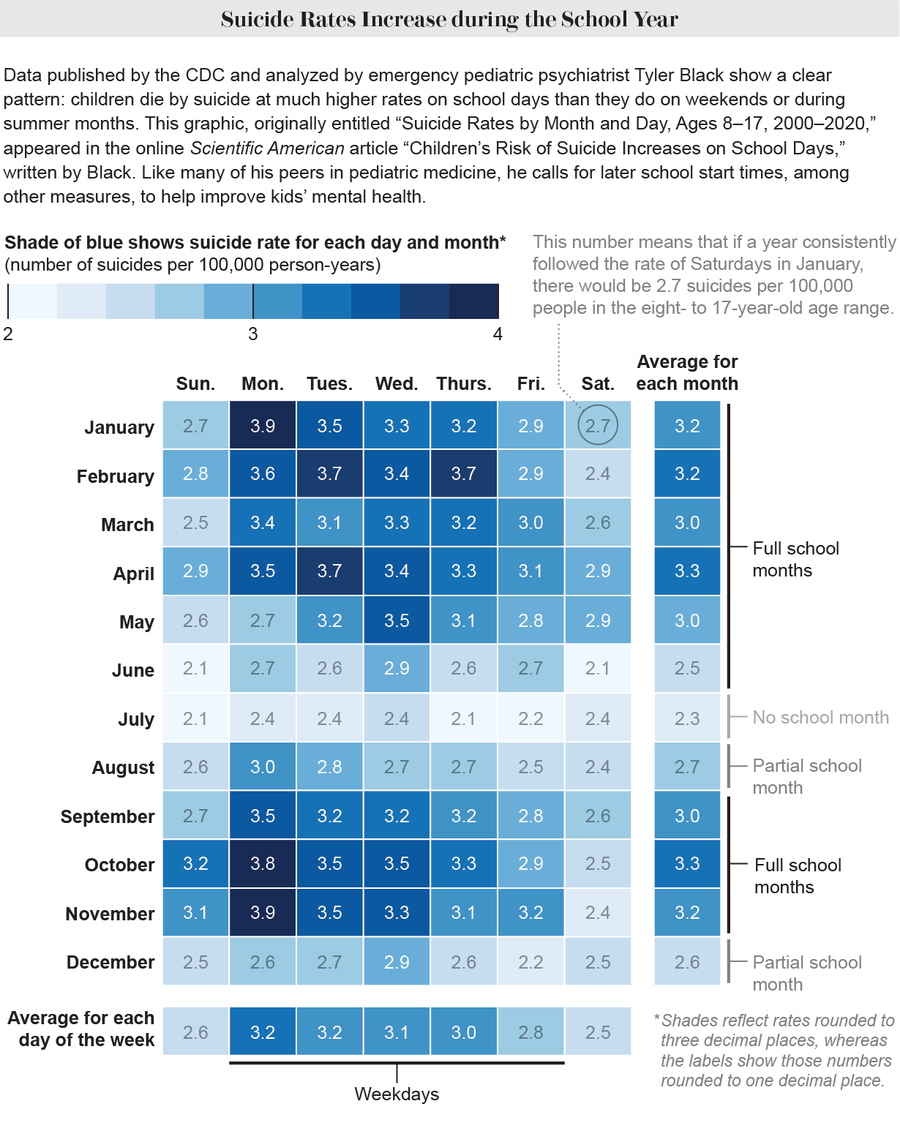

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: CDC Wonder, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Data analysis by Tyler Black

These kids are telling us they need more sleep. In survey after survey, they say when school starts later, they are not as tired all day, they tend to get to school on time, and they are less likely to have to be nagged to get out of bed. They tell us that as their sleep time decreases, their use of tobacco and drugs increases, including drugs that could help them stay awake. They tell us that getting one less hour of sleep a day leaves them feeling hopeless and, sometimes, suicidal. Research has shown that suicide risk in children increases during the school year, and sleep deprivation could be a contributing factor.

Other studies show that getting one less hour of sleep a day is associated with weight gain. Researchers have told us that sleepy teens are more prone to car crashes and that even 30 minutes of extra sleep would help alleviate some mental health concerns. Even teachers have reported that with later start times, their students are more engaged in the morning, and teachers themselves are more rested.

Despite decades of research, thousands of publications and clear science, schools in only a few states and the District of Columbia have pushed their start times to 8:30 A.M. on average, which researchers say is a compromise—a better time would be closer to 9 A.M.

The path to delayed school start times is riddled with potholes. Bus schedules have to change. Teacher and administrator schedules have to be altered. After-school sports and enrichment programs might have to begin later. Parents and caretakers with more than one child may have to juggle childcare for older children to get the younger ones to their earlier start times. A delayed school start could also mean adults with inflexible work schedules are late for work.

Experts say our agrarian model of education was designed to get teens up early and home before dark to tend to the farm, but it is no longer relevant for most modern students. Our cultural views of teens as lazy and of needing sleep as a weakness are harmful and inaccurate. And our grumbling that if we survived early start times, today's teens can, too, is callous and dismissive of science.

Access to education is a basic right in the U.S. But it's time to stop thinking of school start times as immovable mountains. While more states ponder start time legislation, school district administrators should prioritize it, and people running for school boards need to add start times to their platforms. State-level funding agencies have to clear hurdles for districts wanting to try this. Employers need to be more flexible to help parents adjust to school schedules, especially with hourly employees. And the unions that represent teachers and other education professionals need to negotiate with teens also in mind.

For decades we've ignored the overwhelming evidence that delayed school starts help teens succeed. It's time to let teenagers sleep.