Editor’s Note (8/21/23): This story is being republished because smoke from wildfires in western Canada is affecting air quality across the Pacific Northwest.

The average American may have already inhaled more wildfire smoke in the first eight months of this year than during any recent full year.

What’s responsible for the record? Canada’s unprecedented blazes, which began in late April, have sent plumes of smoke south to the U.S., impacting communities in the Midwest and along the East Coast that are unaccustomed to wildfires. This event is undermining a decades-long trend toward generally cleaner air in the U.S., driven by decades of reduced anthropogenic pollution. Now experts hope the shock of 2023’s smoke will inspire collective and individual actions to reduce future wildfire smoke exposure.

This year “fire activity has been near historic lows in most of the western U.S.,” says Marshall Burke, an economist at Stanford University. “Yet this will likely be the worst wildfire smoke year on record in the U.S. and [is] entirely due to Canadian fires. So that’s really new.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

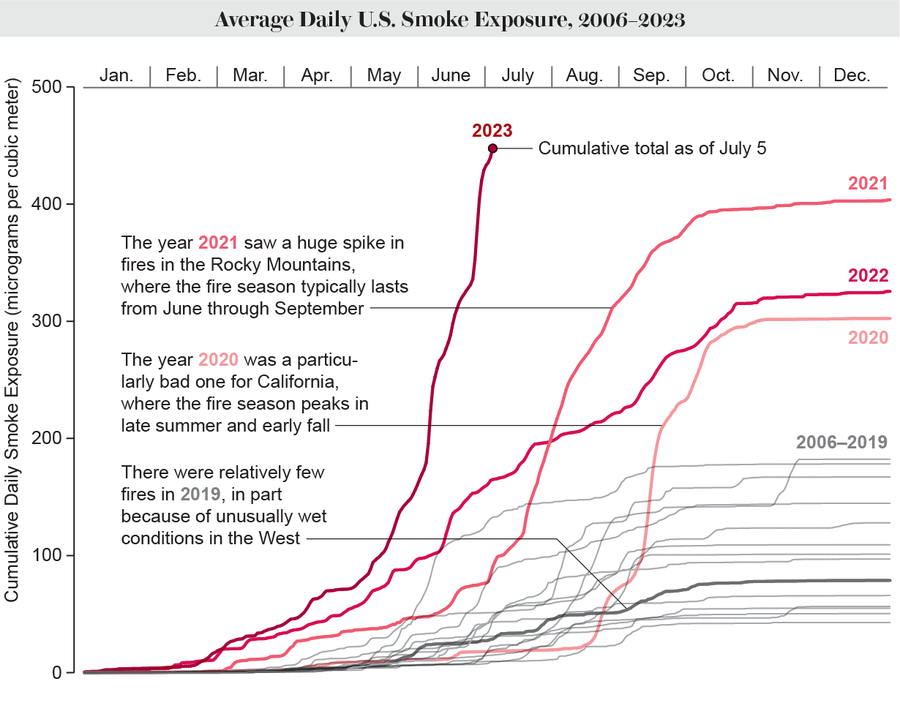

Burke and his colleagues calculated that by early July, the average American had been exposed to nearly 450 micrograms of smoke per cubic meter (µg/m3). When they ran the same analysis back to 2006, they found the largest exposure of those years came in 2021. Over the course of that year, the average American was exposed to just more than 400 µg/m3, in part because of a particularly active fire season in the Rocky Mountains. The years 2020 and 2022 also brought significantly above-average smoke exposure, which was driven by fires in the western U.S. as well.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: Environmental Change and Human Outcomes Lab (ECHOLab), Stanford University

“That increase in wildfire exposure is really reflective of not just more fires but more fires lasting for longer and impacting large population areas—so just more people being exposed to more smoke for longer periods of time,” says Delphine Farmer, an atmospheric chemist at Colorado State University, who was not involved in the exposure analysis. “That trend has been increasing over the last decade, and I am unsurprised that we are hitting a maximum this year.”

Burke and his colleagues relied on satellite data first gathered in 2006 to figure out where smoky skies predominated. By combining those data with general air pollution measurements from sensors on the ground, they could calculate how much of the smoke was low in the atmosphere, where people can breathe it in. Finally, the researchers incorporated local population density to determine about how much smoke Americans were breathing.

The approach isn’t perfect, Burke and others note—surface sensors don’t distinguish between wildfire smoke and other types of small particle pollution, such as that from local factories. And some experts question whether, for example, a median analysis that would be less influenced by outliers would be a more meaningful approach than the national average.

But the calculation is one way to illustrate the extraordinary nature of this year’s fire season, Burke says.

Typically U.S. wildfires—and the smoke they create—are contained in the West. But this year a wet winter has led to below-average fire activity in the West, while Canada has seen more than 5,000 fires burn more than 13 million hectares, according to Natural Resources Canada. Weather patterns have sporadically funneled smoke from fires in eastern Canada south over the densely populated Eastern Seaboard, quickly exposing large numbers of people to high levels of smoke, albeit briefly.

“What’s troubling about this event is that so many, many people were affected,” says Loretta Mickley, an atmospheric chemist at Harvard University, who wasn’t involved in the exposure estimate.

With more than 120 million people in the eastern and Midwestern U.S. exposed to that smoke, this year’s average exposure soared, Burke says.

Wildfire smoke contains tiny particles that can travel deep into the body and wreak havoc, particularly on the respiratory and cardiac systems, says Carrie Redlich, a pulmonologist and occupational environmental medicine physician at the Yale School of Medicine, who wasn’t involved in the exposure analysis. There’s still a lot that doctors don’t know about the impacts of wildfire smoke, however. Much of the research is based on general air pollution, and it’s difficult to tease apart the role smoke played in any given health outcome, Redlich says.

The impacts of short bursts of high smoke exposure are even trickier to pinpoint. “For any given person, it’s not like their two days [of wildfire smoke are] going to give them lung cancer versus not,” Redlich says. “But when you multiply the risk over millions of people, which is what’s happened, then there is the public health [concern].”

Christa Hasenkopf, an air quality data expert at the University of Chicago, who calculates the impact of air pollution on life expectancy, says that it takes about two weeks of high air pollution to start to see health impacts in these analyses. But she also emphasizes that some of the worst air quality in the U.S. this summer is a regular occurrence in places such as Delhi. Globally, she says, air pollution reduced life expectancy in 2020 by an average of about 2.2 years. In the U.S. that number was 2.5 months, and the county with the worst air that year—Mariposa County, California—would experience a 1.7-year decrease in life expectancy if those conditions became the norm.

Experts also underscore that even during a remarkably bad year for wildfire smoke, U.S. air is much cleaner than it has been. “Most of the measures would suggest that, on average, the air is still much cleaner than it was even 15 years ago or definitely 30 years ago,” Burke says.

“The background story here, which is really important, is the monumental success we have had in improving air quality,” he says. But if smoke worsens, he warns, that overall picture might start to shift. “Wildfires are really pushing back on that pretty hard.”

Burke says that the same Clean Air Act legislation that cleaned up power production and vehicles could be adapted to tackle wildfire smoke, including by encouraging prescribed burns. These purposefully set and carefully monitored fires can reduce the odds of large, uncontrollable blazes by burning through fuel.

Farmer says she hopes this year’s high smoke exposure will encourage just such activities. “We also need to realize that we have the opportunity to change and impact our wildfire smoke exposure, and we have tools that we can use,” Farmer says. Even individuals can take action to reduce their exposure by using purifiers—even homemade ones—to clean indoor air.

“Could there be a dystopian future? Well, yes, there could,” Farmer says. “But I think we have to look at it from the perspective that we have tools we can implement to avoid that. I really hope that this summer is a wake-up call to policymakers and politicians and the public in general to start thinking about those tools.”