Hot weather—along with extreme humidity levels that are usually associated more with the sultry U.S. Southeast—has enveloped much of the Midwest and will move into the mid-Atlantic states over the course of this week. The phenomenon will bring some of the summer’s hottest conditions and will potentially smash more records.

The soaring temperatures reach into the mid- and upper 90s Fahrenheit (upper 30s Celsius), as much as 10 to 15 degrees F (5.6 to 8.4 degrees C) above normal for this time of year. They come courtesy of an atmospheric high-pressure area that has moved into the region from the Southwest. Such areas are called ridges because of their appearance on air-pressure maps, and they block storms that could bring cooler conditions. The clear skies associated with high-pressure areas also let more of the sun’s rays beat down on and heat up the ground.

This is “a strong ridge even for midsummer” and even more so for the tail end of the season, says Andrew Taylor, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service’s (NWS’s) Lincoln, Ill., office.* That strength is what could cause some daily temperature records to be tied or broken.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The heat is accompanied by humidity from two sources: moist air that is streaming up from the Gulf of Mexico and a phenomenon that is sometimes called “corn sweat.” The latter happens when corn, soybeans and other crops release moisture as the temperature climbs. This process, known technically as evapotranspiration, is akin to how humans perspire in the heat. Steamy contributions from those crops mean “we can see some of our higher moisture values of the year at this time of year,” Taylor says.

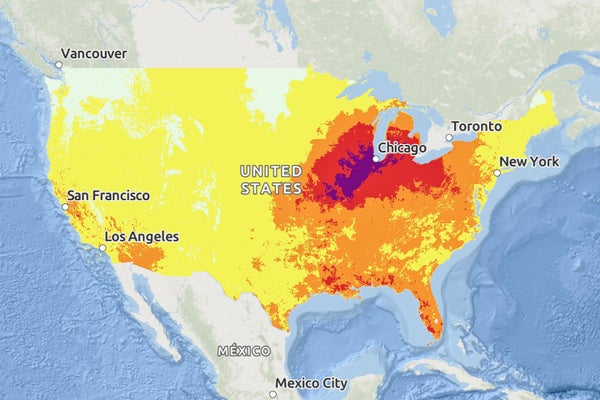

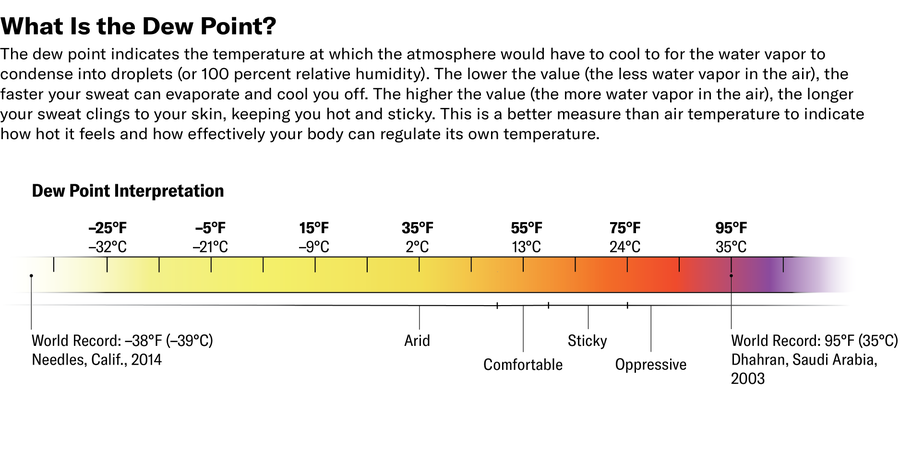

This influx of moisture is pushing dew points as high as the 60s and 70s F (upper teens and low to mid-20s C). (The dew point is the temperature that the air would have to be cooled to in order to let water vapor start condensing out of the atmosphere.). In some places dew points are even reaching the low 80s F (mid- to high 20s C). Those below about 55 degrees F (13 degrees C) can feel reasonably dry and pleasant, but things start getting sticky at around 60 degrees F (16 degrees C)—and downright miserable if this measurement reaches the 70s F.

Zane Wolf; Source: National Weather Service (data)

When temperatures and humidity are both high, the risks for heat illness rise considerably. Elevated humidity makes it harder for the body to cool itself via sweating because the air is already so full of moisture that perspiration doesn’t evaporate.

Heat indices—which give a sense of how much hotter the temperature feels because of the humidity—will reach 105 to 115 degrees F (41 to 46 degrees C) in some of the worst-affected areas of the Midwest. (It will feel even hotter in direct sun because the heat index is calculated for shade.)

HeatRisk—an experimental new tool from the NWS that incorporates temperature, humidity and data on when heat-related hospitalizations tend to rise in a given area—is in the “extreme” and “major” categories, the two highest, for much of the region.

Taylor and other meteorologists emphasize that people need to be very cautious if they’re doing anything outside, especially working, exercising or taking part in other activities that involve high exertion. Prolonged exposure to such conditions can result in heat exhaustion, the signs of which are fatigue, dizziness, nausea and a cessation of sweating. If a person with this condition doesn’t get to a cooler location or receive prompt treatment, heat exhaustion can progress to heat stroke: in the latter, the body loses its ability to cool itself, an extremely dangerous situation.

Taylor says that if people need to be outside, they should take frequent breaks in the shade or find an air-conditioned space whenever they can. You should also “try to limit the time that you’re outside during the late morning to early evening hours” and drink plenty of water, he says.

In areas of the northern Midwest such as Minnesota, heat-related health concerns are particularly high because the current heat wave coincides with the region’s busy state fair and college move-in days, along with other activities “where you have such a large congregation outdoors,” says Joe Calderone, a meteorologist at the NWS’s Twin Cities office. Those concerns are especially high for at-risk groups such as young children, older adults, those who have various health conditions or take certain medications, people who work outdoors and the unhoused.

“Those who have small children, make sure to check your back seat” when exiting a car, Taylor cautions. There have already been 27 deaths of children who were left in hot cars so far this year, according to the NWS. Taylor also warns of the risk to pets that are left in cars or that spend prolonged periods outside.

Temperatures will also be elevated at night, with lows only down into the 70s F, which further raises the risk of heat illness. “When there’s little relief overnight, there’s more heat stress,” says Ashton Robinson Cook, a meteorologist and forecaster at the NWS’s Weather Prediction Center.

Heat waves such as this one have never been unheard of or even rare. But they are becoming hotter and happening more frequently than in the past because of the added heat trapped by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as a result of burning fossil fuels.

This heat wave won’t linger for too long, though. A slow-moving cold front will begin moving into the most northern U.S. areas, creeping under the heat wave late on Monday night and early Tuesday. And “eventually the bulk of the heat and the worst of the heat indices will slide east,” Cook says. Eastern areas will also cool down some later in the week as the front continues to push eastward.

*Editor’s Note (8/27/24): This sentence was edited after posting to correct the relevant National Weather Service office.