Amid temperatures above 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees Celsius) on July 3, 2023, then 70-year-old Bob Woolley stumbled while walking across his Phoenix-area backyard and fell on its rocky surface. He touched “the ground hoping to catch myself, and I was startled by how hot and painful the rocks were,” he said at press conference on July 2, 2024. “I tried pushing up with my hands, and it was so painful, I couldn’t keep my hands in contact with the ground for an effectively long enough time to move. They just kept burning.”

Eventually, he said, “I looked at my hands, and the skin had peeled off my palms like the skin from an onion.”

He tried pushing up with his forearms—but they burned, too, turning “charcoal black,” he said. Woolley tried to shimmy “like a sidewinder rattlesnake” and was burned on his leg from his calf to his hip. His wife eventually heard him, and she and her son got him inside. He ended up at the local burn center with third-degree burns over 15 percent of his body, as well as some second-degree burns. Woolley underwent several grueling surgeries to remove the burned skin and to receive skin grafts. Even the recovery was painful, he said. “Changing the bandages everyday felt like being skinned alive,” he added.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Ordeals like Woolley’s are becoming steadily more common in Phoenix, and they represent a heat risk that health professionals say is often underestimated by the public: contact burns from touching sizzling-hot pavement. With climate change raising temperatures everywhere, it could become a bigger problem in many cities.

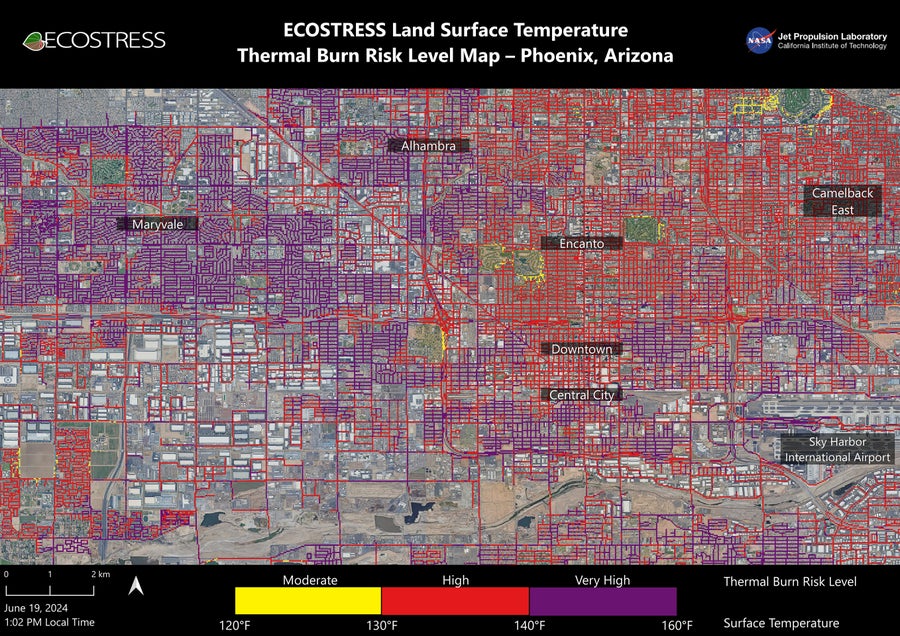

A new NASA map of pavement temperatures across the Phoenix area underscores how widespread the threat is in the famously hot city. The map was made using data collected at about 1 P.M. local time on June 19 by an instrument called the Ecosystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station (ECOSTRESS) onboard the International Space Station. It shows where asphalt and concrete surfaces reached at least 120 degrees F, or 49 degrees C (yellow on map below). Many roads in the city went above 140 degrees F, or 60 degrees C (purple).

NASA’s ECOSTRESS instrument on June 19 recorded scorching roads and sidewalks across Phoenix where contact with skin could cause serious burns in minutes to seconds, as indicated in the legend above.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Asphalt’s dark color and the nature of its ingredients make it absorb 95 percent of the solar radiation that hits it. Streets can easily be 40 to 60 degrees F (22 to 33 degrees C) hotter than the air temperature on very hot days. “I don’t think people realize how hot that asphalt gets,” says Glynn Hulley, a climate researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The lighter color of concrete means it gets less hot than asphalt, particularly if it is new. Weathered concrete is darker and can get hotter.

The map clearly showed that urban areas with more shade-providing trees were cooler than those without them, which has also been observed in other cities Hulley and his colleagues have studied. The team hopes this work can help cities know where to target heat reduction interventions, such as planting trees or painting streets white.

The risk from pavement burns is highest for babies, young children and the elderly because they are less able to quickly pick themselves up. Unhoused populations are also at higher risk.

Kevin Foster, director of Valleywise Health’s Diane & Bruce Halle Arizona Burn Center, which treated Woolley, said during this week’s press conference that Phoenix pavement temperatures can easily reach 160 to 170 degrees F (71 to 77 degrees C). That “is not that far away from boiling,” Foster noted. “Really it only takes just a fraction of a second to get a really significant burn with surfaces that are that hot.”

Though such burns can happen anywhere with pavement that gets hot enough, Arizona is unique in the scope of the risk. “There really isn’t any other place in the country that sees those types of burns,” Foster said.

The Diane & Bruce Halle Arizona Burn Center registered a major increase in heat-related burn cases last summer, when the U.S. Southwest baked under a heat dome and Phoenix had a record 54 days of temperatures above 110 degrees F. The center admitted 136 patients with severe burns in June–August 2023, up from 85 in that period in 2022. One third of the patients required ICU care, and many needed surgery, including skin grafts. Fourteen died from their injuries. Many of the patients who came in with burns also suffered from heat stroke.

The center, which expanded to handle more patients this year, had 50 admissions this past June alone, Foster said at the press conference. These have mostly been older men “just taking a walk,” he added, “and they go down, and they can’t get back up again.”

Foster cautioned people—especially those most vulnerable—to avoid going outside during the hottest times of the day. If they do, they should tell someone where they are going or ask someone to go with them.

Kristie Ebi, a University of Washington epidemiologist who specializes in heat-related health risks, says public awareness of these risks is lacking, and she hopes more media coverage will help. She has heard reports of such burn injuries sustained during a 2021 heat dome event in the famously temperate Pacific Northwest—suggesting this problem can crop up almost anywhere.

Woolley hopes telling his story will spur others, especially older individuals, to be prepared. At the press conference, he said that prior to his burn, he wouldn’t have thought it could happen to him. But “I'll tell you, it can happen to you,” he added. “And as a senior, if you fall, it’s harder and harder to get up.”