Extreme heat has left hundreds of millions of people sweltering in record-breaking temperatures above 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit) over the past few weeks across a broad swath of Asia. From the Palestinian territories in the west to India, Thailand and the Philippines to the east, scorching conditions have caused at least dozens of deaths, ruined crops and forced thousands of school closures. Relentless heat waves have worsened the already precarious conditions for those living in refugee camps and in makeshift housing in dense urban areas. And the 1.2 degrees C of warming the world has already experienced has significantly cranked up such events’ severity, a new analysis shows.

That trend of worse and more frequent heat extremes will only continue in these and other places “if you don’t do anything to stop burning fossil fuels,” says the new study’s lead author, Mariam Zachariah, a researcher at the Grantham Institute–Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London.

The analysis was conducted by an international team of researchers called World Weather Attribution (WWA), which uses peer-reviewed methods to look for the fingerprints of climate change in extreme weather events. The scientists use trends in historical temperature data, along with computer models, to compare the severity and frequency of extreme events in today’s real-world climate with those in two projected scenarios. One was a simulated world without human-caused climate change, and another was a future under continued warming.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The group focused on three areas: “West Asia” (the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, Israel, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan), “Southeast Asia” (the Philippines) and “South Asia” (which, in the team’s analysis, included India, Bangladesh, Vietnam and Thailand).

World Weather Attribution, restyled by Amanda Montañez

The team found that the weeks of April heat in South Asia this year were about 45 times more likely and 0.85 degrees C hotter because of human-caused climate change. The researchers had carried out two studies in roughly the same region in 2022 and 2023, and this year’s trends in temperature data were on par with the earlier results. “This keeps happening every year,” Zachariah says.

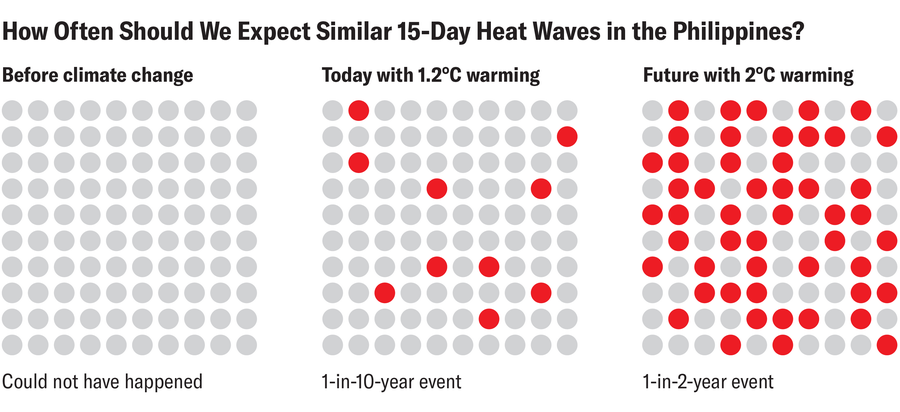

In the Philippines, the team analyzed a 15-day period of heat at the end of April. Though this is usually the hottest time of year for the archipelago, the researchers found that an event of this magnitude would not have happened without the influence of climate change—which made this particular heat wave 1.2 degrees C hotter. There was also a discernable impact from this year’s El Niño, which added another 0.2 degree C.

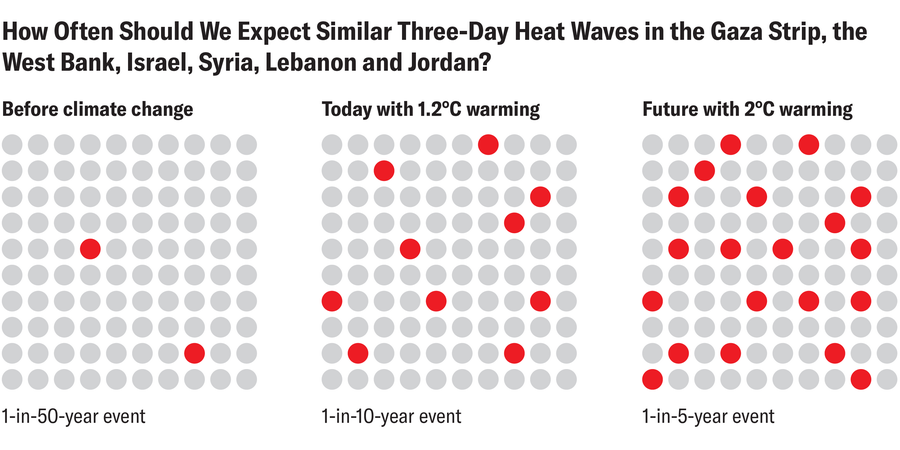

West Asia’s seasonal weather patterns are closer to those of much of Europe and North America, where temperatures usually don’t peak until later in the summer—so the three days in which they rose above 40 degrees C in late April were unusual. The team’s analysis found that climate change made that April heat wave five times more likely and 1.7 degrees C hotter.

Such heat has enormous impacts on people, particularly displaced and impoverished populations with extremely limited means to cope. Zachariah, who has family in India, says relatives “talked about how hard it was to get things done” in the “scorching heat”—and they have had proper housing, which many in the area have lacked. Thousands of schools have shut down in South and Southeast Asia for parts of April and May because of the heat, a situation the researchers say can widen the education gap between high- and low-income families. The heat has also posed a health risk to many who work outdoors, such as construction workers, farmers and truck drivers, and it can mean they earn less money.

World Weather Attribution, restyled by Amanda Montañez

Many of the 1.7 million displaced people in Gaza are living in tents that tend to trap heat, and the high temperatures exacerbate drinking water shortages and already dire health conditions. Many in the territory are experiencing famine, and Israel’s bombardments have devastated hospitals and other care facilities.

With greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere continuing to rise (there was a record annual jump in carbon dioxide levels over the past year), events with a similar meteorological setup will be even worse in the future. With two degrees C of warming, heat waves like the recent one in West Asia would become more frequent by a factor of two and would be another one degree C warmer. The heat in the Philippines would become another five times more likely and 0.7 degree C hotter.

“If humans continue to burn fossil fuels, the climate will continue to warm, and vulnerable people will continue to die,” said the new analysis’s co-author Friederike Otto, a climate scientist at the Grantham Institute–Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London, in a recent press release.

Many areas, including parts of India and Bangladesh, “will soon reach unlivable conditions,” Zachariah says.

The results point not only to the need to rapidly phase out fossil fuels but also to the necessity of better policies and infrastructure to help people adapt to the damage that has already been done. For example, the analysis mentions that although India has a robust action plan to notify people of extreme heat and advise them on measures they can take to get by, workers need mandatory protections such as rest-shade-rehydrate programs. “We shouldn’t focus only on the numbers we report,” Zachariah says. “It is also extremely important to consider what these numbers contribute to.”