There are a number of Black inventors who have become part of our national consciousness. Polymath agricultural scientist George Washington Carver and cosmetics creator and entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker are two. There are many more who have directly influenced U.S. society and culture in major ways, but their achievements have largely been omitted from the canon of top innovators. Here are three who changed the chemical industry, the garment business and household work, and telecommunications.

Norbert Rillieux (1806–1894)

Sugar, all too ubiquitous today and consumed without much thought, was once a luxury item restricted to the wealthy. High prices were the result of limited supplies, and those limits existed because sugar processing was arduous and dangerous. On plantations, sugarcane juice was boiled to evaporate out the water, eventually producing sugar crystals. Enslaved workers scooped the thickening liquid from one open cauldron to another to increase its concentration. Their working conditions were sweltering, injuries were common, and fuel was costly. Yet this was the standard method of production until a clever Louisianan named Norbert Rillieux upended it.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

One of several patent drawings that Norbert Rillieux sent to the Patent Office. Patent Case File No. 3,237, Improvement in Sugar-Works, Inventor: Norbert Rillieux.

Credit: U.S. National Archives

Rillieux was a free Black man who was educated in Paris, since New Orleans schools would not admit him. He excelled in engineering, particularly on projects that employed steam. In his day, steam powered society. He wrote papers about steam engines and ways of maximizing the vapor in a vessel heated by steam. While in Europe, he also theorized about ways to improve the evaporation of sugar juice, a process he became familiar with when he was a boy. He returned to New Orleans to apply these ideas.

Rillieux devised an effective mechanized multistep method for juice production. Instead of using people to transfer liquid with increased sugar content from one cauldron to another, he connected several sealed vacuum pans together with pipes, and linked one of those pans to a steam engine. Instead of heating each individual pan with a flame below it, steam from the engine boiled the liquid in the first pan. The vapor produced during that evaporation process wasn’t wasted, but instead directed through a pipe to the next pan and used to heat it. Each successive pan was heated by the vapor of the previous pan. The sugar liquid, which also flowed from pan to pan, increased in concentration with each step and this process saved on fuel. Lastly, Rillieux employed the thermodynamic principle that pressure and temperature follow each other—as one changes so does the other. By lowering the pressure of each successive pan, he lowered the temperature needed to boil the juice, which prevented the sugar from caramelizing.

The inventor revolutionized sugar processing by taming steam and thermodynamics. Rillieux’s apparatus—now called the multiple-effect evaporator—is used in modern industries worldwide, such as food processing, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. His name was once well-known, and many sugar-processing firms in the 19th century prided themselves on using a “Rillieux system,” but references to him evaporated in the last century. Yet it is clear this pioneer in chemical engineering made our lives sweeter.

Sarah (Marshall) Boone (1832–1904)

The corset was a fashion craze in the 19th century. This fitted undergarment ushered in an age when dresses had very narrow midsections. In the late 19th century, an hourglass shape was heralded as a thing of beauty. But the tiny waists made life difficult for dressmakers, who needed to iron out wrinkles before putting their wares on display. The common arrangement for ironing at the time was a long rectangular plank placed on two chairs. Yet the shape of the plank made it nearly impossible to insert it into a dress and to press an iron onto wrinkles at a narrow waist or small sleeve. A wrinkled garment would not attract customers, so ironing became a serious obstacle to profits. One inventor named Sarah Boone overcame this problem by making a new ironing board.

Patent drawing for Sarah Boone's ironing board, awarded April 26, 1892.

Credit: U.S. National Archives

Boone was born on a North Carolina plantation. In 1847, she married James Boone, a free man who likely bought her freedom. By 1856, they moved to New Haven, Conn., which was a hub of industry from carriages to clocks. New Haven was also the epicenter of the corset industry, producing nearly 70 percent of the world’s supply. Boone was a dressmaker who decided to come up with a better way to iron these tight fitted dresses. She received U.S. Patent 473,653 on April 26, 1892 for an ironing board. Her objective, as she stated in her patent application, was “to produce a cheap, simple, convenient, and highly effective device, particularly adapted to be used in ironing the sleeves and bodies of ladies' garments.”

Many of the elements of her design are common in ironing boards today. Her board narrowed at one end, and it was padded and collapsible. It isn’t clear that Boone made any money from her innovation. But some scholars argue that acquiring a patent was an achievement in itself, particularly since she was one of the first African American women to get one. She lived in a time when society limited her agency, but she pushed back. Boone not only came up with a unique design, she also learned to read and write so she could study comparable inventions and fill out her patent application. Teaching the enslaved to read was illegal in the south when Boone was growing up. She learned as an adult, probably at her church.

Her patent not only highlights her ingeniousness; it characterizes the spirit of self-actualization held by freed Black people. Formerly enslaved people wanted to enter society, improve themselves and make a better life for their children. Boone did so as a homeowner, as an entrepreneur and as a pillar of her community. She was also an engineering vanguard. While there are no monuments to honor her, her brainchild sits in the closet of most homes.

James West (1931– )

Since the inception of the telephone, society has been captivated by it. But the first telephone was beset by shortcomings. Alexander Graham Bell’s invention had difficulty picking up certain consonants, which is why Thomas Edison’s improved microphone became the standard way of converting sound vibrations into an electrical signal. But even Edison’s invention had a limitation. It required a large battery to operate. That changed when James (Jim) West created a microphone that revolutionized the way we communicate.

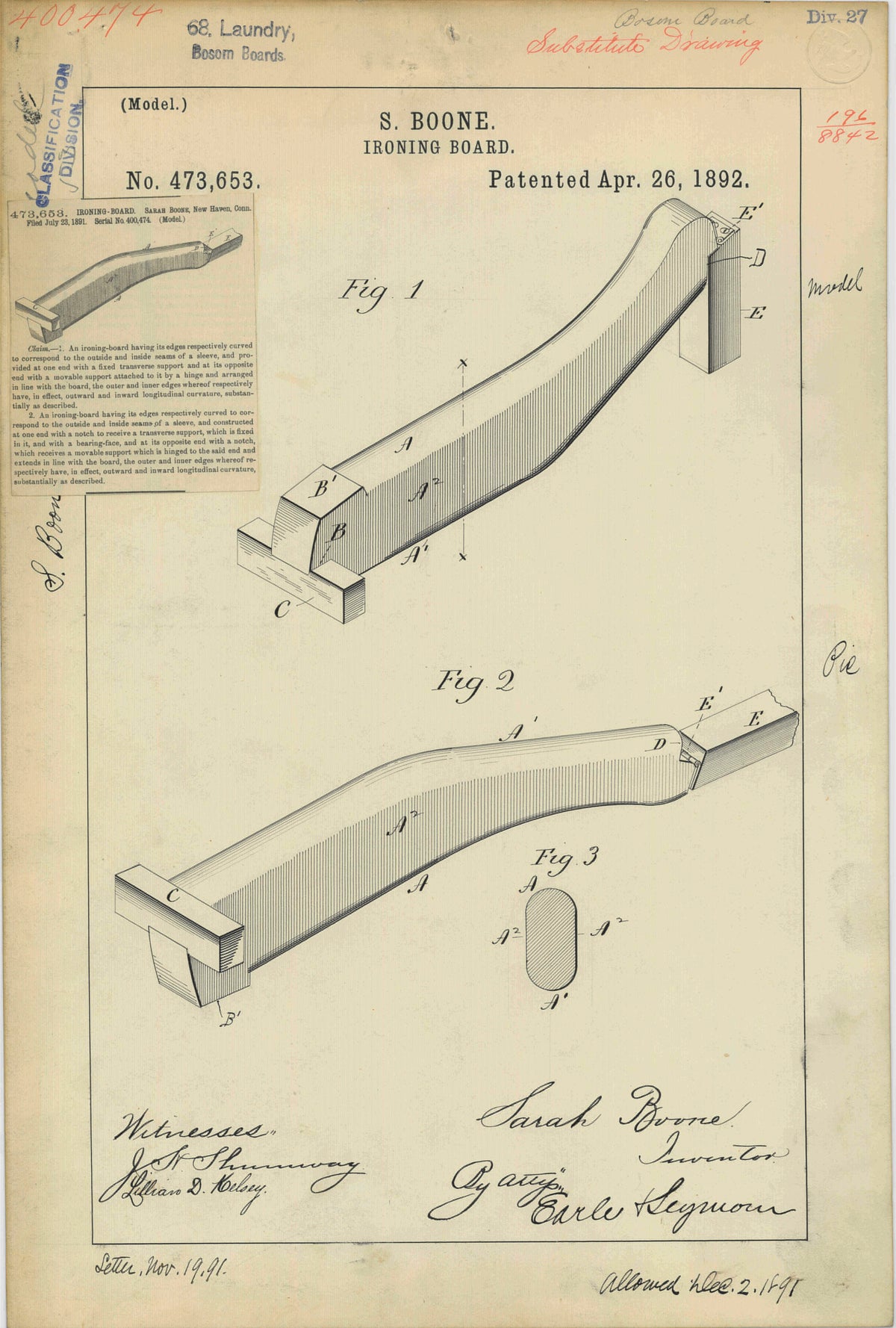

Patent drawing for Gerhard M. Sessler and James E. West - Bell labs: electroacoustic transducer and foil electret condenser microphone.

Credit: FLHC 60 Alamy Stock Photo

West was born in Virginia and had dreams of becoming a scientist. His parents tried to dissuade him, because his father knew three Black chemists who could not get work in a laboratory. His parents’ opposition was so strong that they refused to pay his college tuition. Despite this, West struck out on his own and eventually enrolled at Temple University in Philadelphia. While a student there, he spotted an ad for a summer internship at Bell Labs. Bell Labs was the birthplace of storied innovations such as the transistor and the precursor to the laser. Getting an internship at the lab was a chance to dwell among science elite, and West leaped at the opportunity and got it.

As an intern, West’s task was to make a set of headphones. His design consisted of a stretched sheet of plastic (Mylar) hovering over a metal plate. The plastic sheet was connected to one end of a power supply, and the metal plate was connected to the other, giving them an opposite charge. When an oscillating electrical signal was introduced, the plastic Mylar responded by vibrating, which created a sound.

One day West accidently disconnected the power supply and then heard something strange. A sound was coming from his supposedly powerless headphones. After investigating, he discovered that the Mylar plastic was storing an electrical charge, making it possible for his headphones to work without added power. In the Bell Labs library, he found that there was a class of materials called electrets that stored an electrical charge and that Mylar was one of them. This discovery sparked his microphone idea. In headphones, electrical signals transform into sound. In a microphone, the reverse happens, and sound transforms to an electrical signal. West decided to make a microphone using this strange-behaving material. It worked, and this was a major breakthrough. By eliminating the battery, West’s microphones could be miniaturized. Today his invention sits in standard telephones, cell phones, computer tablets, and hearing aids around the world. Nearly two billion are made annually. Yet few people have heard of the scientist who made it possible for them to communicate.

Rillieux, Boone and West are just a few of the thousands of Black inventors who have touched our lives, each overcoming challenges to bring about their innovations. What connects them all to us is their indomitable desire to create. Every person has the capacity to make something, from an apple pie to an algorithm. We best nurture this ability within our generation—and the next—when we highlight a diverse range of individuals. The achievements of these inventors, and our celebration of them, establish that creating is part of our communal heritage. The ability of these Black inventors to overcome major obstacles—both social and technical—can also inspire all of us to persevere against the challenges we all face.