Earlier this week news broke that independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., claimed to have once had a dead worm in his brain. Kennedy had been experiencing memory loss and mental fog, and he originally suspected these symptoms might be caused by a brain tumor. Brain scans in 2010 showed a cyst that his doctors said contained remains of a parasite. The findings and other health issues were revealed in a New York Times article based on a review of a deposition for his 2012 divorce, as well as an interview the outlet conducted with him.

The revelation drew attention in the worlds of politics and parasitology. “I woke up to all kinds of messages from friends in parasitology,” says Shira Shafir, an epidemiologist and an associate adjunct professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, in response to the news.

The species of the purported parasite in Kennedy’s brain was never identified, and he did not know where he got infected. A spokesperson told media outlets on Wednesday that Kennedy had traveled extensively to Africa, South America, and Asia and likely contracted the parasite on one of the trips. Several parasites can affect the central nervous system and potentially create cysts in brain tissue. While relatively uncommon in the U.S., such infections can be devastating in many parts of the world. For example, the World Health Organization estimates there are between 2.56 million and 8.3 million people around the globe living with neurocysticercosis, a brain infection caused by the pork tapeworm Taenia solium. “It's a really big deal in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, India and other parts of Asia. It’s a leading cause of acquired seizures,” says Clinton White, a parasitologist and infectious diseases professor at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. “Neurocysticercosis is a major disease, and it's kind of funny [these are] the circumstances in which people are paying attention to it.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Scientific American spoke with Shafir and White to discuss how parasitic worms may infect the brain, what symptoms they cause and how infections are diagnosed and treated.

[An edited transcript of the interviews follows.]

What are parasitic worms, and which ones can infect the brain?

SHAFIR: We generally don’t have adult worms that end up in the brain. What does end up in the brain are parasites in their earlier developmental stages, such as eggs or larvae—or, for lack of a better word, baby worms. So generally the parasitic infections that can impact the brain are those of pathogens in early developmental stages, which, for the most part, accidentally make it into the brain.

I study a few parasitic infections that impact the central nervous system. The most common one is Taenia solium, the pork tapeworm. It has an incredibly complicated life cycle in which individuals get infected by consuming undercooked infected pork. [But] there is no chance that, through the consumption of undercooked pork itself, someone could develop neurocysticercosis.

Other species that I work on are Baylisascaris procyonis [the raccoon roundworm] and Angiostrongylus cantonensis [the rat lungworm], both of which can produce larvae that will travel through the [human] body in order to try and find the tissue that they prefer and that can accidentally end up in the brain. And they can cause some really significant neuropathological changes.

Walk me through the life cycle of Taenia solium. How does it infect humans?

SHAFIR: Definitively, pigs are the natural hosts. So pigs get infected with a tapeworm. When it is in the pig, it penetrates the intestinal wall and goes to the musculature. The musculature is obviously the part of pigs that people consume. So humans, if they consume uncooked or undercooked infected pork, can get infected with the intestinal form of the tapeworm. And then they will pass eggs in their feces, and if those eggs are consumed by pigs, the pigs get infected, and that kind of continues, on and on. But if, accidentally, another human or the infected human themself—because many people don’t have great hand hygiene—comes into contact with the fecal material and swallows the eggs, the eggs will then hatch, they will penetrate the intestinal wall, and they’ll circulate [in the bloodstream] to the musculature. They can then end up in any organ throughout the body, but most commonly they go to the subcutaneous tissues, as well as the brain and the eyes.

So if you eat raw pork, you get a tapeworm—that’s an intestinal problem. If you come into contact with fecal material from a person who has the intestinal tapeworm, that’s how you end up with this neurological manifestation.

What are the symptoms of neurocysticercosis?

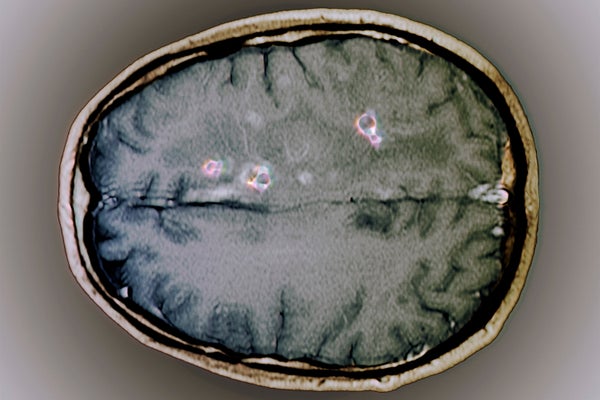

WHITE: The disease from infection with T. solium in the tissues is called cysticercosis, and when it infects the brain, the disease is called neurocysticercosis. In most places [in the body] the larvae don’t cause a lot of problems and end up dying. Those that end up in the brain can survive for a few years, and they usually do not cause a lot of problems. The cysts, these little round, balloonlike structures, are about a centimeter in diameter and are clear, fluid-filled sacs. Sometimes the cysts can become big enough that if they get into the fluid around the brain, called the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), they can get stuck at little openings in the brain and block the flow [of CSF]. That leads to hydrocephalus [swelling of the brain], and that’s often fatal unless the patient undergoes emergency surgery. But usually the cysts don’t cause a lot of problems—it’s the inflammatory response that you get when [the larvae] are starting to die and dying that can cause problems—particularly seizures.

SHAFIR: Once [the eggs of T. solium] get to the musculature—either the musculature of the pig or the musculature of a person—they're going to “encyst,” which essentially is a cute little cuddly term for parasites rolling up into a ball and creating a protective structure. That process can happen in the brain. And depending on where in the brain [the cysts] are, they can disturb pretty important brain functions.

The [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] actually has some really striking images of what it looks like when someone has neurocysticercosis. There are these cysts, or little balled-up eggs, in the brain—it has a very Swiss-cheese appearance.

Can the condition cause memory loss?

WHITE: No, it usually doesn’t directly cause much in the way of memory loss. If you do careful psychological tests, you may see some minor [memory] problems, but [this] wouldn’t be a common symptom. If someone has had frequent seizures, however, they can end up with memory loss. People wouldn’t describe brain fog or memory problems. As an aside, those are more typical of mercury poisoning. [Editor’s Note: According to the New York Times, Kennedy has said he also experienced mercury poisoning around the time he had learned of his parasitic infection. Mercury exposure has been linked to central nervous system damage that can cause memory loss and Alzheimer’s disease.]

According to the New York Times, Kennedy claimed that the worm that infected him “ate a portion” of his brain. Can tapeworms “eat” brain tissue?

SHARIF: Discussions of eating brains are better left in zombie movies than in legitimate scientific discourse. The parasitic infections that impact the brain do not eat the brain. Now, that doesn’t mean that they cannot damage brain tissue. But that kind of inflammatory language indicates a lack of scientific literacy and is pretty concerning.

How is neurocysticercosis diagnosed and treated?

WHITE: The main diagnostics are imaging studies of the brain, such as a [computed tomography (CT)] scan or magnetic resonance imaging. Some of the findings on those scans can be confused with other things, however, so there are confirmatory tests that look for antibodies to the parasite. The CDC developed an excellent test that's very specific to the pathogen—a lot of the commercial tests are not that accurate. More recently, scientists have developed what's called a PCR test and an antigen detection test, and those are really quite helpful, particularly in severe cases. The treatment starts out with addressing the symptoms. If a patient has seizures, you should give them antiseizure medicine. If they have hydrocephalus, they may require neurosurgery. Anti-inflammatory steroids and antiparasitic drugs often hasten the demise of the parasites, and their use can be associated with somewhat fewer seizures. Sometimes it takes repeated treatments to kill them, but they do die. They don’t live forever even if you don’t treat them. There are cases [in which the larvae cause] calcified lesions that have been there for a long time in which you can get damage to a part of the brain called the hippocampus. This can be associated with seizures that are not relieved until you have surgery.

How common are these infections?

SHAFIR: Generally, cysticercosis [and neurocysticercosis are] far more common in low-income regions, including those in Latin America. We do a lot of work with communities from [there]. Because part of the tapeworm’s life cycle requires that individuals consume raw or undercooked pork and that [this meat is] allowed to be infected, we generally don’t see tapeworm transmission in the U.S. because of our robust [U.S. Department of Agriculture] inspection process. This means that the individuals who are getting infected are either from communities where it is common for pork to be infected or have traveled to those countries. Here in the U.S. we have about 1,000 hospitalizations each year—and those happen in the states where you have the greatest amount of international travel, such as New York, California, Texas and Illinois.

It is unfortunate that these parasitic infections, which disproportionately impact individuals in low- and middle-income countries, only get the attention and discussion when a high-profile individual gets infected. There are thousands of people throughout the world who are dealing with legitimate [problems] from these parasitic infections. We underfund research. We underfund the development of new treatments, which are not prioritized until they become front-page-worthy news because they’re impacting someone who is notable.