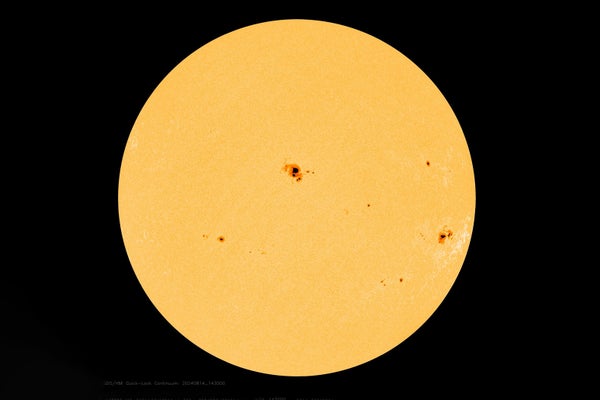

The sun’s getting feisty.

Our star is nearing (or even at) the peak in its magnetic cycle, which means lots of solar storms—such as the big one that lit up the skies with auroras in May—as well as sunspots. Most of these sunspots are small enough to warrant the use of a telescope to see them, but some get so big that they can be spotted (so to speak) with the naked eye—well, an adequately protected eye, that is. And they can be bigger than our entire planet—a lot bigger.

So how do these blemishes on the sun’s face form, and how can you safely view them?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The sun is hot. No surprise there, of course. Our star’s temperature increases with depth, peaking in the sun’s core at 15 million degrees Celsius. But even at the surface, it’s a blistering 5,500 degrees C. Come to think of it, blistering is the wrong word because such heat would actually vaporize your face, not just give you a sunburn.

At these temperatures, the heat is great enough to strip electrons from their parent atoms, a process called ionization. The resulting matter is no longer just a gas but instead a plasma, with electrons free to move around in it.

Electrons have a negative electric charge. A basic law of physics is that a moving charge creates a magnetic field, and there are a lot of electrons inside the sun. They’re not just moving higgledy-piggledy, either. The sun’s hot core heats the cooler overlying layers, churning up that material in a cyclic process called convection. You’ve seen this before right here on Earth: hot air rises, and cool air sinks, which is how hot air balloons can stay aloft.

Inside the sun, convection creates huge flows of plasma—thousands of conveyor-belt-like towers moving all those free charged particles around. This motion creates a magnetic field that each tower carries along with it, and that field is strong, thousands of times the strength of Earth’s magnetic field.

The plasma and its associated magnetic field rise until they reach the sun’s surface. Normally the plasma would cool and drop back down, but sometimes the magnetic fields of multiple towers get tangled up, holding on to the plasma like a net and preventing it from sinking. The plasma cools on the surface, dropping in temperature by more than 1,000 degrees C. Hot objects emit light, and the hotter they are, the brighter they are. The magnetically trapped plasma is cooler than the surrounding solar surface, so it appears dark, silhouetted: a sunspot.

For reasons that are still not terribly well understood, the overall magnetic activity of the sun waxes and wanes over an 11-year period, often called the solar cycle. Right now we’re approaching solar maximum, when the magnetic activity peaks. This should happen in late 2024 or early 2025, and that means we’re currently seeing more sunspots. It also means more solar storms: Magnetic fields can carry vast amounts of energy, and the tangled fields can suddenly snap and release that energy in a terrifyingly powerful solar flare, which can explode with as much energy as billions of nuclear bombs. This can also trigger a coronal mass ejection, an eruption of a billion tons of plasma from the sun’s surface that surges out into the solar system at high speed. If one sweeps past Earth, its magnetic field can interact with ours, funneling subatomic particles into our planet’s atmosphere and ionizing the air. When these torrents of electrons recombine with atoms in Earth’s atmosphere, they emit light in specific hues of green, yellow and red. These vibrant displays follow the shape of Earth’s magnetic field, creating billowing auroras in the sky.

Most sunspots are a few thousand kilometers across and too small to see without aid from binoculars or a telescope. But some grow to enormous size, tens of thousands of kilometers across or more. Earth is 13,000 km wide, so these giants can be much larger than our planet. Once sunspots reach about 40,000 km wide, they are large enough to be resolved by the human eye. These naked-eye spots have been seen for millennia; the earliest recorded sighting was by Chinese astronomers nearly 3,000 years ago.

So how can you observe them?

Under normal circumstances, the sun is far too bright to look at safely. It’s not just the intensity of the light but also radiation in the form of ultraviolet and infrared light that can damage your retina, so just using dark sunglasses isn’t adequate. In fact, sunglasses make things worse because the darkened sun allows your pupils to dilate, which lets in even more of the damaging radiation. So please don’t try that.

Eclipse glasses are your best bet, and Scientific American has a description of how they work. If you have some left over from the solar eclipse that swept across North America in April, you’re all set. If not, the American Astronomical Society has a list of eclipse glasses vendors, and most are relatively inexpensive. I have a few pairs and keep them near south-facing windows in my house, ready to go if the sun decides to sprout a monster. Another option is to use a piece of welder’s glass with a “shade number” of 14 or higher (the larger the shade number, the darker the glass). That’s assuming, of course, that you happen to have some number-14 welder’s glass lying around! Also, some binoculars and telescopes are designed specifically to observe the sun, and they have the added benefit of giving you a far more detailed view of solar activity. They can be pricey, though.

Technically it’s also sometimes possible to view the sun safely at sunset, when it’s right at the horizon and its light is attenuated by passing through a lot more of Earth’s air. That can block most of the damaging light. “Most of” is carrying a lot of weight here, though, so I don’t recommend trying to observe the sun even in these somewhat more favorable circumstances.

Now it’s just a matter of patience and clear skies. The sun has already produced four naked-eye spots this year: one in February, another in May and a fortuitous double-whammy of two at once in early August, which I saw myself. You can check SpaceWeather.com to see if any big ones are visible or go to NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory site. At the latter, scroll down to the image labeled “HMI Intensitygram - colored” to check for current sunspots on the sun’s Earth-facing side.

There’s no guarantee, but it’s a safe bet that additional enormous sunspots will emerge as the sun’s magnetic cycle continues to ramp up. They can even appear for some time after the solar maximum, possibly as much as a year or two later. So stay alert, stay prepared, and you might be able to see some of the biggest structures in the solar system with your own eyes.