This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

More than 200 years ago, the Scottish botanist William Roxburgh published Hortus Bengalensis, a thick book cataloging hundreds of medicinal plants collected at the East India Company’s botanical gardens in Calcutta.

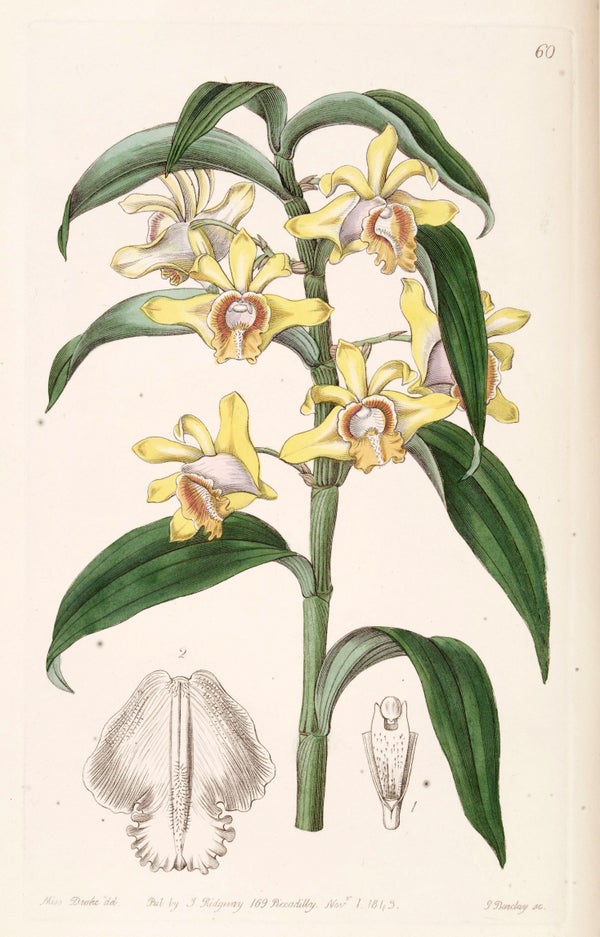

Among the hundreds of plants appearing in the book’s pages was an orchid originally collected in the Chittagong region of what is now Bangladesh. Identified at the time as Cymbidium alatum, the orchid now goes by the taxonomic name Theocostele alata.

You can’t find the species in Bangladesh anymore, though. No one has officially observed Theocostele alata there since Roxburgh made note of it in 1814.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

And it’s not alone. According to research published this month in the International Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Theocostele alata is one of 32 orchid species native to Bangladesh that no longer appear within its borders.

That represents the extinction of 17% of Bangladesh’s 187 known orchid diversity.

Researchers call the loss “alarming” due to the flowers’ ecological uniqueness and their potential medicinal, horticultural and ornamental values.

“If this rate continues, there will be no trace of orchids in the near future,” says Mohammed Kamrul Huda, a professor of botany at the University of Chittagong and lead author of the study.

.jpg?w=600)

Vrydagzynea albida by Carl Ludwig Blume from Collection des Orchidées les plus remarquables de l’archipel Indien et du Japon, 1858. Credit: Wikimedia

Huda and his colleagues spent nearly a quarter of a century, from 1996 to 2019, conducing field research throughout Bangladesh to catalog the country’s existing orchids and look for previously described species. They even searched herbariums and private collections for species they couldn’t find in the wild, to no avail.

The paper blames habitat destruction for most of the disappearances, although it’s hard to determine exactly when these orchids went extinct in Bangladesh. In most cases the last official observation of a species, like the plant described by Roxburgh, occurred more than a century ago.

A species called Anaectochilus roxburghii, which grew in damp gullies at the edges of forests, was last recorded in 1830 near Sylhet, a large and culturally important Bangladesh city. Huda and his coauthor Ishrath Jahan, also with the University of Chittagong, blame the area’s “rapid deforestation” for the orchid’s disappearance.

Another species, Habenaria viridifolia, grew in the Lower Bengal region and hasn’t been observed since 1890. The paper ascribes its disappearance to habitat destruction and overexploitation.

And then there’s Spathoglottis pubescens. This species, which once grew near Sylhet and Chittagong, was last seen in Bangladesh in 1999—ironically enough, by Huda and his fellow researchers. Its last known habitat was developed shortly after the observation.

The Bigger Picture

Experts say the loss of orchid species in Bangladesh embodies similar problems that orchids face around the world.

More than 1,500 orchid species currently appear on the IUCN Red List, the international database of threatened species and their known extinction risk. Of those 195 are assessed as “critically endangered,” 349 as “endangered,” 185 as “vulnerable to extinction,” and 74 as “near threatened.” Another 212 species appear on the Red List as “data deficient,” meaning no one knows how well they’re doing in the wild.

That’s just a fraction of the estimated 30,000 orchid species worldwide, but the Red List still provides a snapshot into the conservation status of these unique plants, which face threats ranging from habitat loss to overzealous commercial exploitation. Collectors have been known to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for rare orchids, and the trade has already driven several species extinct. In one of the most recent examples, collectors wiped out 99% of a newly discovered species in Vietnam once they got word of its location (many researchers now keep species locations secret to avoid a repeat of the tragedy).

_-_The_Orchids_of_the_Sikkim-Himalaya_pl_300_(1889).jpg?w=600)

Gastrochilus calceolaris by G. King and R. Pantling from The Orchids of the Sikkim-Himalaya 1889. Credit: Wikimedia

The loss of local orchid species affects people, too. Many are edible or have medicinal qualities, and familiarity with orchid species plays an important role in nearby communities. Orchid declines in China, for instance, were accompanied by a loss of traditional knowledge associated with the orchids and a decline in their cultural role, according to a study published this month in the journal Anthropocene.

So why are so many orchids at risk, despite the ubiquitous nature of some well-known varieties in our garden stores and grocery shops?

For one thing, habitat loss and illegal trade are hard forces to counter.

For another, most orchid species are not commercially or even experimentally cultivated—because we don’t know how to do so.

In part that’s because orchids evolve in incredibly specific habitats. Take them out of those conditions and they simply don’t grow.

It’s more than depending on a certain temperature range or given pollinator: Orchids evolved to rely on very specific fungi at different points in their life cycles. Each species has a series of symbiotic relationships (called mycorrhizae) with various fungi, first as seeds and then as adult plants. If we don’t know which fungi an orchid species uses throughout its life, then we can’t grow them.

And the truth is we don’t know much about most of those fungi.

“There are certain groups of fungi we know are more common with orchids than other groups,” says Dennis Whigham, founding director of the North American Orchid Conservation Center. “But at the species level, they’ve just never been described. In my lab we have the largest collection of living orchid mycorrhizae, and probably 99.9% of the ones that we’ve analyzed are new to science.”

If orchid habitat is destroyed, we could potentially also see the extinction of unique resident fungi.

“When we change the environment, the fungus is probably the first thing to sort of bite the dust,” says Whigham. “When that happens, it’s impossible for the orchids to be sustained.”

Back to Bangladesh—and Beyond

Although the habitat that these extinct orchids needed may no longer exist in Bangladesh, there could still be hope for some species.

For one thing, it never hurts to keep looking. Huda reports that even though field expeditions failed to turn up those 32 species, other surprises awaited them. “We rediscovered some orchid species while doing field observations,” he says. “Some of them were thought to be extinct by other researchers.”

And few of these species, like Acanthphippium sylhetense—last seen in Bangladesh around 1880 or 1890—have been successfully cultivated in other countries for years. Even Theocostele alata, the species last seen by Roxburgh, occasionally turns up for sale online in the United States—for as little as $29.99.

Finally, many of these species have historic ranges spreading beyond Bangladesh into other countries and may still exist there. Even Spathoglottis pubescens, the species Huda himself last observed in Bangladesh, is still known from India and China.

That doesn’t necessarily mean these wider-ranging species are in the clear. In fact, it’s impossible to know. Of the 32 species Huda and Jahan list as regionally extinct in Bangladesh, only four have been assessed by the IUCN. Podochilus khasianus appears on the Red List as a species of “least concern,” although the listing notes it has disappeared from four countries and its presence in one more is “uncertain.” Paphiopedilum venustum (the “charming paphiopedilum”) and P. insigne (the “splendid paphiopedilum”) both appear as “endangered” due to “ruthless collection for regional and international trade.” Gastrochilus calceolaris is listed as “critically endangered” because of habitat degradation and trade—an assessment that hasn’t been updated since 2004.

Huda says other nations should take their study as incentive to protect these 32 species, as well as other orchids within their borders.

“If those countries meet the same factors responsible for the loss of species in Bangladesh, the same result may happen,” he cautions. “Immediate action plans are required from conservationists and leaders on a global level to protect these beautiful and valuable species.”

As for Bangladesh, Huda and his colleagues have now turned to assessing the 155 species that remain there. They hope to determine the various species’ conservation status and suggest possible remedies to prevent further biodiversity loss in the country. “Maybe we can look through the status of other plant species as well to evaluate the degree of threat,” he suggests.

And he hopes others will join them. “I think all conservationists and researchers of biodiversity should work to raise awareness regarding these issues,” he says.

“This is a global issue,” echoes Whigham. “We need to conserve hotspots where there are a lot of orchids now and use scientific approaches to figure out how to grow and restore native species in the future.”

Unfortunately, the time to pay attention to orchid conservation grows short as species around the world continue to lose ground or disappear. Bangladesh is just one example, but it wasn’t the only one announced this month. Just a few days after Huda’s paper appeared, another study in the journal Oryx suggested that nine more orchid species from Madagascar—each observed by scientists just a single time—may have also joined the ranks of the extinct.

Sadly, more are sure to follow.

This post first appeared on The Revelator on January 27, 2020.