This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

A team of Indian conservationists working to save a critically endangered tree from extinction just achieved an important conservation success, but first they had three major stumbling blocks to overcome.

The first was, of course, numbers. The trees, known only as Madhuca insignis, are few and far between. Originally declared extinct more than a century ago, the 60-foot-tall, fruiting species was rediscovered in 2004. A year later it was added to India’s national priority list of endangered trees, but few if any actual protection efforts followed. By the time conservationists finally conducted the first major survey of the trees’ population—a three-year process between 2013 and 2015—only 27 individuals remained.

“We were really shocked and disappointed by that number, because previous records indicated 50 individuals in the wild,” says Anurag Dhyani, one of the paper’s authors and a scientist at Jawaharlal Nehru Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute in Kerala. “However, this is the case for most of the threatened trees in the Western Ghats and other parts of India.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

M. insignis fruit with seed. Credit: Geeta Joshi

Roads, agriculture and other development have taken their toll on many of these tree species, including M. insignis, and those threats are getting worse: A planned hydroelectric plant in the Dakshina Kannada region would, if completed, wipe out 10 of the remaining M. insignis trees and harm the populations of 47 other rare plant species.

As if the tiny population and ongoing threats weren’t bad enough, the researchers encountered a second obstacle: Just 7 of those 27 trees were flowering and producing seeds.

And that led to the third challenge: The fruit-covered seeds themselves proved…difficult. A paper the researchers published in November 2019 in the Journal for Nature Conservation goes so far as to call them “recalcitrant.”

“They are short-lived—maybe a few weeks,” explains Dhyani, one of the paper’s authors. “They have a high moisture content, which enhances microbial contamination and leads to rapid deterioration.”

The seeds also obstinately refused preservation methods. Dhyani says they can’t be dried to a moisture content level below 30 percent without injury, and they don’t tolerate freezing. “So storage in a seed bank is not feasible,” he says.

Åsmund Asdal, coordinator for the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, who was not involved in this project, says trees like this produce what’s called “non-orthodox” seeds which defy normal preservation methods. Orthodox seeds, by contrast, “can be dried down to a very low moisture content—3 to 5 percent water in the seed—and still keep the ability to germinate. This characteristic is necessary for long-term storage in below-zero conditions.” Many trees and bush species produce unorthodox seeds, which he says are more common in tropical areas such as Southeast Asia.

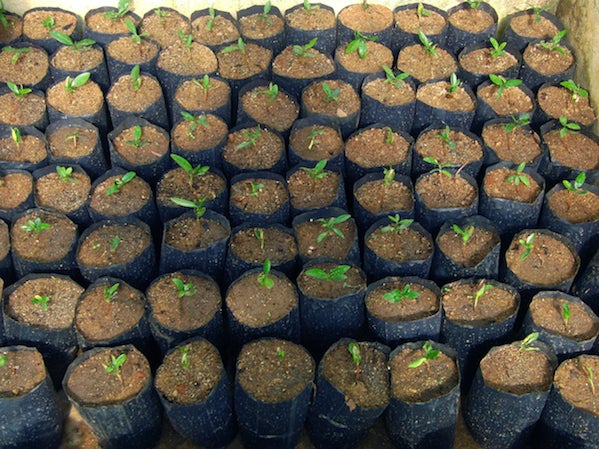

But from those difficulties, the first signs of success have emerged. The researchers managed to collect 300 M. insignis seeds, which they quickly planted in a nursery. Amazingly 275 of the seeds germinated—producing ten times as many seedlings as adult plants existed in the wild.

Within a year the seedlings had grown to heights of six inches or more—big enough to transplant 100 of them into Agumbe forest, one of their original habitats, which currently contains just two adult trees. By March 2019 a full 60 percent of those transplanted saplings had survived, and they’d reached heights of up to two feet—possibly enough to enable their long-term survival.

That’s critical, because the trees’ own nature may provide their own stumbling block in the wild. M. insignis is a river-based tree that, the scientists observed, tends to drop about three-quarters of its seeds into the flowing water. The rivers deposit the floating seeds on banks farther downstream, where they germinate in just two weeks, but the resulting seedlings don’t yet have the deep roots of their forebears and have a tenuous hold on the future. The researchers observed many of them get washed away during the monsoon period’s heavy rains.

M. insignis is a river-based species. Credit: Geeta Joshi

If M. insignis had remained a populous species, it probably could have overcome that low recruitment rate just based on the greater number of seeds it would have produced. But with so few trees remaining and even fewer producing fruit, too few seedlings currently survive naturally. That’s why it needs a helping hand, something that might benefit other species as well.

“Based on my 10 years of research experience with endangered plants in the temperate and tropical region of India, I strongly feel collecting seeds and raising seedlings in the nursery to a certain size—3 to 12 months—is of immense importance for rare plants,” says Dhyani. This will provide seedlings with a greater degree of safety from weather events, predators and pest insects.” Then, once the plants are big enough to be transplanted, they can be monitored to see how well they grow and survive—and, it’s hoped, the next round of seedling growth can begin.

M. insignis seedlings. Credit: Geeta Joshi

Of course all of this takes money, sources of which are few and far between for endangered plants.

“It took a long time to start our conservation efforts on this rare tree,” says Dhyani. “One of the major factors is that funding for conservation projects is very limited globally, and major shares flow toward big cats, bears, elephants, rhinos and sharks. Plants are less funded, despite the universal fact that we cannot live without them. It’s a big challenge for young conservationists like me.” The current study was funded by the Karnataka Forest Department, but local agencies can only handle so much.

Still, Dhyani and his colleagues are already putting their experience with the species to good use. “We have initiated a rescue operation on Buchanania barberi, an evergreen endemic tree with two mature individuals remaining in the wild, and Indian sandalwood (Santalum album), the second most expensive wood in the world,” he says.

As for the future of Madhuca insignis, Dhyani says they’ll continue to monitor the transplanted seedlings: “Our success will be defined by whether they successfully flower and fruit.”

He hopes the rediscovery and successful germination of this tree will plant the seeds for other, similar initiatives.

“I believe these small steps will help to inspire other conservationists and the public to work and support other plants in urgent need of conservation globally,” he says. “It’s really difficult to say what form it will take, but surely we could save some species with little effort.”

This post first appeared on The Revelator on December 12, 2019