This week, President Joe Biden will sign the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 into law. The legislation includes nearly $53 billion in funding to encourage domestic manufacture of semiconductor chips, as well as continued research into this field. “CHIPS” stands for “Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors,” but the act goes beyond computer components: it proposes big funding increases for the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Standards and Technology. It also sets new policies for NASA, including extending support for the International Space Station through 2030 and reorganizing a program for sending humans back to the moon and eventually to Mars.

Because so many fields rely on computer chips, the new law’s effects will go well beyond the semiconductor industry, says Russell Harrison, acting managing director of the U.S. branch of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE-USA), who has been consulting with politicians on the legislation for the past few years. “Actually, I’m trying to think of industries that wouldn’t be dependent on them,” he adds. Scientific American spoke with Harrison about what the CHIPS and Science Act covers, and how this will impact the U.S.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

What types of science, technology and exploration does this act support?

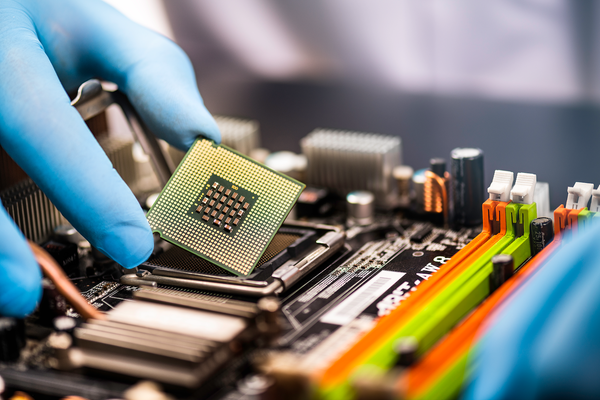

All of them! That’s not quite true, but there’s a lot in there. First of all, it’s important to note that the bill basically has two sections. There’s the CHIPS Act: it’s fairly focused and fantastically good for semiconductors and related industries, which IEEE is obviously quite excited about. It truly does support the semiconductor industry and the associated businesses: it’s not just [funding] the production of semiconductors, it’s also all the things you need to produce semiconductors—design, packaging, a holistic look at the industry. We need to highlight that because the CHIPS Act of the bill is “appropriated funds.” That is, it’s real dollars and therefore that money is going to be spent. Most of the money is going into industry and supporting industry investments. Of the $52.7 billion in subsidies, the bulk of that will end up going to private companies. One of the themes that runs throughout the bill is support of domestic manufacturing, which is important because manufacturing produces a huge percentage of jobs in this country—it always has. The research stuff [includes] $11 billion [over five years] in general research and development within the Commerce Department for anything in this space.

What about the support for science programs, including NASA?

You look at all the rest of the bill—all the energy stuff and the NSF [National Science Foundation] research—all of that is “authorized” money, which means it’s not real yet: we gotta get it through the appropriations process. So in the NASA section [of the bill], there’s no actual dollar numbers in there. But it does [mention] Artemis, the moon and beyond missions; it does some bureaucratic shuffling to create the structures needed for NASA to survive and thrive in this new space environment that we’re in.

Which industries rely on semiconductor chips?

All of them. Within the chip industry, you differentiate between legacy chips, which are the reliable chips that have been around for a while, and then cutting-edge chips. The CHIPS bill is mostly focused on the really high-end cutting-edge chips, although there’s some language in there for the legacy chips. So looking just at the really high-end chips: artificial intelligence, obviously, is going to be “the faster, the better” for that industry. Communications, same thing. Finance actually needs a lot of high-end chip computing power. The automobile industry relies on an increasing number of computer chips, but they tend not to be the really cutting-edge chips. But as you get into more autonomous vehicles, that power has to be greater, because they have to make more decisions faster. The agricultural sector: people always overlook American ag, but they’re doing some incredibly high-tech stuff in terms of sensing, remote sensing, autonomous vehicles [like] harvesters and farm equipment, that’s going to rely on some of this stuff as well. Energy uses a lot of it: the distributed [energy] generation technology, which is becoming more and more important, relies on some really sophisticated computer modeling. The cybersecurity industry—which is part of everybody else’s industry—relies on advanced technology. The U.S. is an advanced tech country; we’re going to use [chips for] all of it.

What are the cutting-edge chips capable of that the legacy chips are not?

I do know that they are getting ridiculously small. The companies that make these chips are starting to dabble in exotic terrain, like quantum computing, which is phenomenally faster (if we can get it to work) than current chips. At a fundamental level, it’s all about speed. But of course, speed translates into so many other things. When we’re talking about trillions of transactions per second, as opposed to billions of transactions per second, you can start to do stuff that you just couldn’t do with the smaller chips. We get into AI—the number of calculations that are required to do real AI work is just so much fantastically larger than what we were capable of 10 years ago.

Will the bill alleviate the ongoing semiconductor shortages caused by supply chain issues?

It can’t address the problem that we are currently experiencing because you can’t stand up a fab [build a semiconductor fabrication factory] in six months. This is a long-term project. But in the long run, it certainly will help. Long supply chains that cross the globe and involve multiple countries and trans-oceanic journeys are vulnerable. No matter how much effort you put into securing them, they’re vulnerable just because they’re long. Producing chips in this country will make the supply chain simpler, cleaner and easier to protect.

There’s also some sections in there setting up new studies, creating new government organizations, to do a better job of monitoring supply chains across the U.S. economy. So that down the line, we’ll be able to identify these problems sooner, which makes them easier to deal with.

A potential threat to the global semiconductor supply is the increasing tensions between China and Taiwan. Could the CHIPS and Science Act reduce U.S. reliance on international chip production?

Taiwan is a global leader in semiconductor technology. And so CHIPS or no CHIPS, I expect that we will continue to do tremendous amounts of business with Taiwan in this field, because they’re very good at it. The bottom line is, this is cutting-edge technology—whoever can do it best is going to win. Semiconductors are a global industry, and most of the major industrial countries play significant roles. Korea and Taiwan are the big ones. Japan is kind of similar to the United States, an upper-end manufacturer as well as a major research country. Europeans do a lot of great research in this area. The CHIPS Act does incentivize investments in the United States. It also, at times, encourages cooperation internationally. And frankly, securing supply chains globally, which the bill does do, is important for Taiwan and Korea and a lot of our other Asian partners.

What else does the CHIPS Act fund?

Workforce: that is one of the sections of the bill that we are most excited about. Large chunks of this country aren’t really yet involved in the 21st-century economy. The CHIPS Act deliberately tries to change that through regional technology hubs and investments in underserved communities. Investments in workforce development go way beyond graduate students to include undergrad research, also what used to be called vocational training (which we’ll call professional training), certification programs and community colleges. Sixty percent of jobs in this country do not require a college degree; they do require training. And investing in those folks, people that know how to build robots, repair robots, run cybersecurity systems—these are high-paying middle-class jobs and they are absolutely essential for this entire operation.

The CHIPS Act intentionally tries to pull the parts of the country that aren’t involved into this industry and into this work. It is going to have a massive impact on broad prosperity across the United States in the long run. It’s also, frankly, the key to diversity: if you want to bring in populations that are not currently engaged in the STEM fields, you gotta bring industry to them. And that’s exactly what the CHIPS bill does.