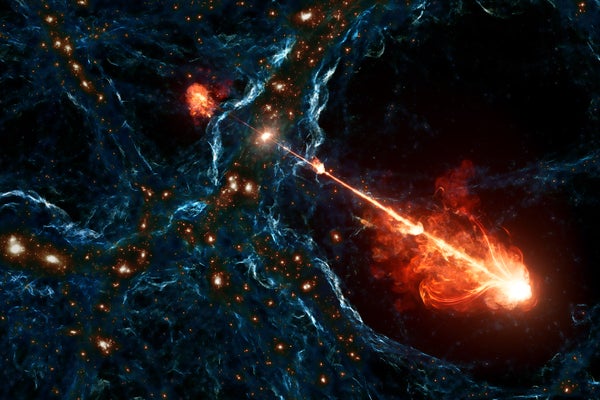

In a galaxy 7.5 billion light-years away, a supermassive black hole shoots out streams of magnetized plasma that span 140 Milky Ways in length. This mind-boggling structure—nicknamed Porphyrion, after a giant from Greek mythology—contains the largest black hole jets physicists have ever seen, a team reported in Nature last month. And its existence suggests that black hole jets may have played a more important role in shaping the cosmos than previously thought.

Black holes occasionally generate jets when they overeat, as matter piles up around their maw and encounters extreme astrophysical forces. All matter that approaches a black hole takes on the form of a spiraling disk. This disk whirls around at such a rapid pace that the material within it glows white-hot and ionizes, transforming into a dense plasma roiling with magnetic fields. A spinning black hole can then twist these magnetic fields into tight cones at each of its rotational poles. Most matter exiting the disk will speed straight into the mouth of the black hole. But a small fraction instead is caught in the twisting fields and slingshots outwards, producing two straight beams that some astrophysicists liken to Jedi lightsabers.

Such jets initially captured scientists’ attention because they served as visual markers for black holes, bottomless pits that are otherwise invisible to most telescopes. Only over time did researchers see the jets as important in their own right: the intense heat the streams gave off sometimes prevented surrounding gas from collapsing and forming into new stars. Such an impact, however, seemed limited because the jets were thought not to stretch too far beyond the confines of their own galaxy, if at all. The sky survey that underpins the new study has complicated that picture by identifying more than 10,000 massive black hole jet systems, chief among them Porphyrion.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Streams as ancient and colossal as Porphyrion may have contributed to some of the early universe’s features, says lead study author Martijn Oei, an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology.

In 2022 Oei and his fellow researchers uncovered another black-hole-spewing jet system that, end-to-end, spans 16 million light-years, or 100 Milky Ways. Porphyrion beats out this previous record holder, Alcyoneus, not only with its absolute size but also with its relative influence on its cosmic surroundings. Born when the universe was less than half its current age and thereby much smaller and denser than it is today, Porphyrion can reach out and touch more than Alcyoneus ever could.

Porphyrion’s jets are estimated to contain the total power of trillions of suns and raise the temperature of surrounding gas by a million degrees Celsius. This means they may have inhibited the formation of not just stars but entire galaxies in the early universe. Their high-speed sprays of magnetized ejecta also could have pierced and filled voids in the cosmic web, the network of matter-rich filaments and matter-sparse cavities that forms the universe’s large-scale structure.

Oei is most intrigued by the possibility that jet systems like Porphyrion may have helped set the stage for life on Earth. Our planet’s magnetic field shields Earth’s biosphere and atmosphere from barrages of high-energy cosmic rays and dangerous outbursts of solar particles and radiation. Yet Earth’s magnetic field is itself embedded in and therefore interlinked with the magnetic field of our star, which in turn lies within other magnetic fields stretching across the Milky Way—and perhaps even beyond. This scalar trail is long and tenuous, but it may trace all the way back through time and space to our own perch on a strand of the cosmic web—and to potential perturbations from structures like Porphyrion.

To better assess the impact such jets may have had on the early universe, researchers will need to create a more comprehensive catalog of the structures. The new study surveys just 15 percent of the sky, possibly leaving many more jets yet to be discovered. And it’s difficult to estimate how many of these gargantuan structures exist, Oei notes, because the conditions that produce and sustain powerful streams remain poorly understood.

That scientists can even make out such large jets is a testament to the sensitivity of modern telescopes. The sheer size of the jets makes them hard to detect in the small field of view available from most suitably powerful telescopes. In the new study, Oei and his team members turned to a European network of radio telescopes called the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR), searching its images of the sky for radio light with a wavelength of approximately two meters. These “human-sized waves” offered signs of “places where something violent and spectacular happens,” he says. When Porphyrion popped up, they used two other facilities—the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope in India and the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii—to discover and study the galaxy that was the source of the signal. Having initially set out to study the cosmic web, Oei found Porphyrion’s pair of jets to be twice the surprise—and he expects countless more as the team continues to study Porphyrion and other systems of gigantic jets.