As a person enters their 60s, the health effects of aging often start to become strikingly clear. Many people begin to use glasses or hearing aids, or their doctors warn them about a sharply increased risk of diabetes or heart disease. But research suggests that our bodies may undergo a dramatic wave of age-related molecular changes not only in our 60s but also in our mid-40s.

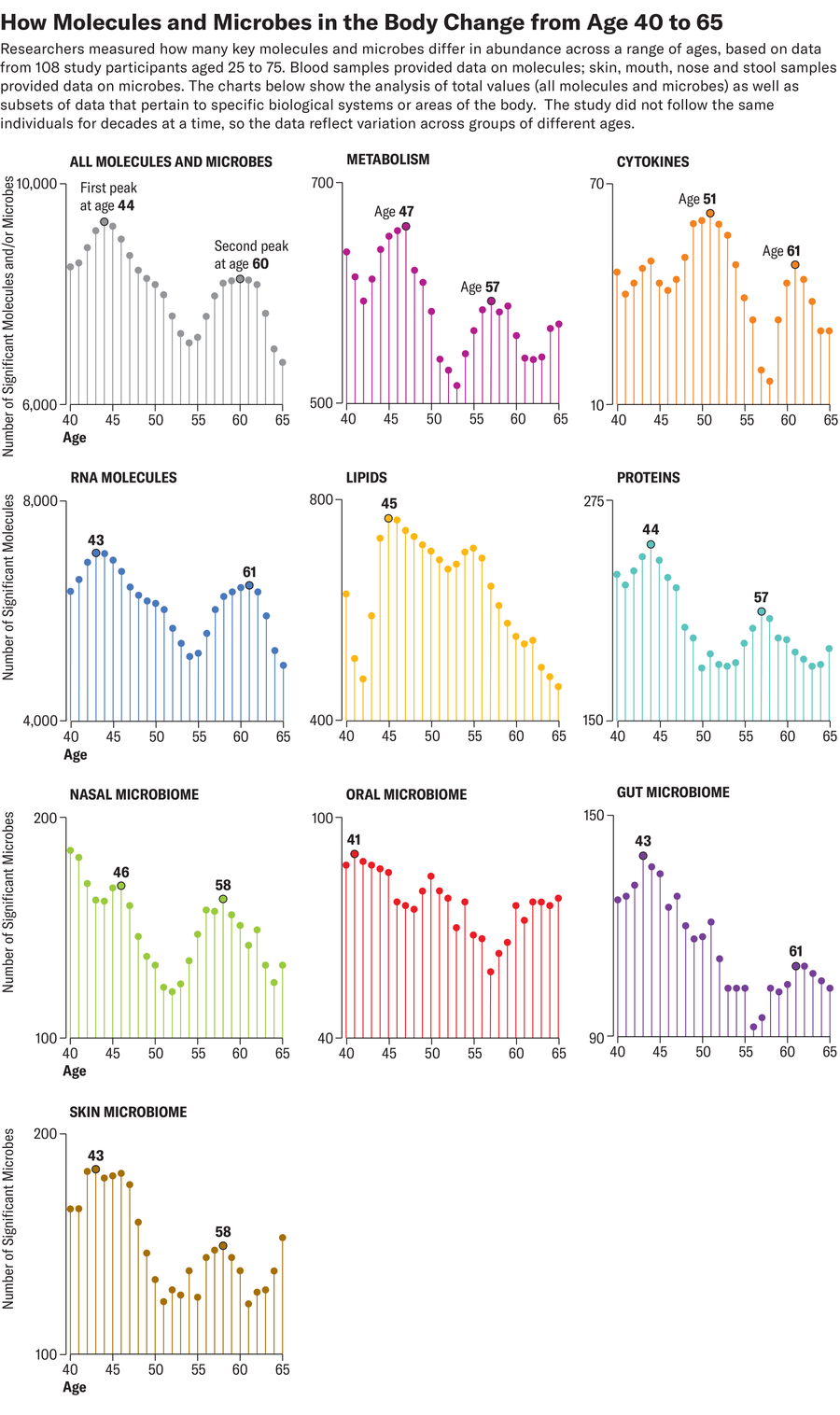

For a study in Nature Aging, researchers tracked the levels of more than 135,000 molecules and microbes, all reflective of activity in cells and tissues, in 108 healthy volunteers aged 25 to 75. Each volunteer contributed biological specimens, including blood and stool samples, every three to six months for a median of 1.7 years. Results showed that changes in many molecule and microbe levels clustered around two distinct time points: ages 44 and 60. The findings suggest that aging might accelerate around those periods—and they signal to experts that our 40s and 50s may be a significant time to closely monitor health.

The study supports many people’s anecdotal reports of noticing changes in their 40s that range from more muscle injuries to worse hangovers, and the data give clues as to why, says senior study author Michael P. Snyder, a genetics researcher at Stanford Medicine.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Compared with younger participants, people in their 40s and 60s displayed biological differences that appeared to be linked to muscle weakness and loss, decline in heart health, and inefficient caffeine metabolism. Those in their 40s also had reduced activity in cellular pathways responsible for breaking down alcohol and fats—possibly a sign that people start to digest these compounds more slowly around this age. People in their 60s, meanwhile, had lower levels of various immune system molecules, such as inflammatory cytokines, which corresponded to a weakened immune response. They also showed significant differences in levels of certain molecules associated with carbohydrate digestion and heart and kidney function, suggesting that the older participants were more susceptible to type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and kidney issues.

The new study’s time points are similar to those identified in a separate 2020 study, in which researchers found that participants’ immune systems grew markedly less adept at fighting off pathogens in their late 30s to early 40s and again around age 65. But the latest study’s findings are not ironclad; it included a relatively small number of people, all living in California’s Palo Alto area. The resulting lack of geographic diversity makes the data less representative of the broader public, notes Aditi Gurkar, who conducts aging-related research at the University of Pittsburgh and was not involved in the recent study. Those sampled likely had some lifestyle factors in common, such as diet, exercise and environmental exposures, which could have swayed the results, she says.

The study also did not follow any individuals for periods longer than about seven years, so scientists cannot be certain that the differences between people in different age groups reflect universal changes. For example, the 40- and 60-year-olds in the study may have aged faster relative to others of the same age in the broader population, Gurkar cautions. She and others say the best way to confirm the results—and to precisely trace age-related biological shifts—would be through a larger study that tracks the same participants over the course of a lifespan. Collecting data on factors such as disease status, physical function or disability could also help researchers better assess the extent to which age-related shifts affect a person’s overall health. (The amount of stress that cells and tissues undergo—referred to as biological aging—varies widely between people of different races and socioeconomic classes, and it even differs between individual organs in a person’s body.)

The reasons ages 44 and 60 might be turning points in health are not yet apparent, but the study authors hope to probe several hypotheses in future work. Snyder suspects that for people in their 60s, declines in immune system function might precipitate a more widespread organ breakdown. A midlife decline in physical activity, meanwhile, could explain the differences seen among people in their 40s—but so might hormonal changes, including menopause. Menopause alone, however, could not explain the trends in the study, Snyder says: male and female participants appeared to show the same degree of age-related differences at both time points.

Snyder suggests the new data can provide actionable health information. People in their 40s might benefit from getting blood tests that track lipid levels, for instance, or from exercising regularly to maintain heart health. Snyder also underscores the importance of early and regular screenings for heart disease for people in this age range who have existing health conditions.

Limitations aside, Gurkar says, the study is a powerful reminder that lifestyle choices such as diet and exercise can accelerate aging—or slow it down. Few studies on aging focus on middle-aged participants or involve biological sampling as comprehensive as that of this paper, she adds. In addition to identifying potential waves of age-related changes, the work provides a crucial first step toward large-scale disease-prediction models based on biological data.