Editor’s Note (10/9/24): Hurricane Milton made landfall on October 9 around 8:30 P.M. EDT near Siesta Key, Fla. At the time, Milton was a Category 3 storm, with sustained winds of about 120 mph. Hurricane Milton is now traveling east-northeast across the Florida peninsula. Its center is expected to reach the Atlantic Ocean tomorrow. Bermuda may experience effects of the storm late on October 12 and into October 13, but Milton will not turn toward the eastern U.S.

Editor’s Note (10/9/24): This story is being updated as the situation unfolds.

In parts of Florida still cleaning up from Hurricane Helene’s damage two weeks ago, a second damaging storm, Hurricane Milton, is causing further devastation.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Milton made landfall on October 9 around 8:30 P.M. EDT near Siesta Key, Fla. as a Category 3 storm with 120-mile-per-hour maximum sustained winds. It explosively underwent rapid intensification on Monday in the Gulf of Mexico, achieving 180-mile-per-hour winds at its peak. Its central pressure—another measure of strength—had dropped to 897 millibars, making it the fifth strongest hurricane ever measured in the Atlantic basin.

Milton then headed northeast, straight toward the western coast of Florida. The worst impact had been forecast to occur around Tampa, but the storm veered slightly south. The first of Hurricane Milton’s rains arrived in Florida early on October 9. This may be Tampa Bay’s closest hit from a serious storm in about a century, although the region, which is home to more than three million people, is no stranger to hurricane damage.

“This is a very serious situation,” says Rick Davis, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service’s Tampa Bay office. “It’s going to affect a lot of people in the state of Florida.” On October 8 U.S. secretary of health and human services Xavier Becerra declared that a state of emergency had begun throughout Florida beginning on October 5. Some 5.5 million people were told to evacuate in anticipation of the hurricane making landfall.

Hurricane Milton was forecast to bring a wide range of threats to west-central Florida: strong winds that could result in power outages lasting up to a week, storm surges of 10 to 13 feet and rainfall totaling six to 12 inches, with up to 18 inches in some locations. Tornadoes were also expected, and the National Weather Service issued around 100 tornado warnings in just six hours on October 9, according to the Washington Post. That’s all happening two weeks after Hurricane Helene, which made landfall more than 100 miles north of Tampa Bay but still wrought serious damage in the region, including causing the highest storm surge since recordkeeping began in 1947.

Tampa Bay is inherently vulnerable to storm surges because its offshore waters are quite shallow, leaving nowhere for water to go but inland. Moreover, Hurricane Milton was expected to arrive at a right angle and hit Florida’s coast head-on. Whereas an arrival at a more oblique angle can push water along the coast, a perpendicular arrangement causes a steeper surge because it more exclusively pushes water inland. The latter would “pile up water faster and faster and faster and not let it recede,” Davis says.

In addition, Helene stripped the area of local defenses such as sand dunes, leaving the region more vulnerable to future surges. The highest storm surge was currently expected to hit just south of Tampa, but Hurricane Milton could still cause twice as much storm surge around Tampa Bay as Hurricane Helene did. (Hurricane Helene killed at least 230 people across the southeastern U.S., including 19 in Florida. A dozen of the latter deaths occurred around the Tampa Bay region.)

The area is also particularly vulnerable to flooding right now, both along the coastline and farther inland. Even before Helene’s hit, the area saw a particularly wet summer, Davis says, leaving the ground saturated and rivers running high. Then came Helene’s surge and downpours; the storm also scattered debris and pushed sand into the area’s stormwater drains, leaving the region even less able to absorb additional water.

Residents of Pinellas County, Florida, fill sandbags at John Chesnut Sr. Park in Palm Harbor, Fla., on October 6, 2024. Florida’s governor has declared a state of emergency on October 5 as forecasters warned that Hurricane Milton was expected to make landfall later this week.

Bryan R. Smith/AFP via Getty Images

As Milton approached Florida, its hurricane’s intensity at landfall was particularly unpredictable because it underwent a process called rapid intensification, during which a storm’s fastest sustained winds increase in speed by at least 35 miles per hour during a 24-hour period.

Hurricane Milton blew that definition out of the water. “It went from a Category 1 to a Category 5 in 18 hours,” says Kristen Corbosiero, an atmospheric scientist at the University at Albany. “It’s a really scary situation.” As of midday EDT on October 7, the storm’s maximum sustained winds were blowing at 175 miles per hour; the previous morning its winds had been just 65 miles per hour. According to the New York Times, only two Atlantic hurricanes on record, Wilma in 2005 and Felix in 2007, are known to have made bigger leaps in intensity over a 24-hour period.

Climate change is expected to increase the number of storms that undergo rapid intensification. It’s too early to analyze in detail the role of climate change in the season as a whole, but other hurricanes this year, including Hurricanes Beryl, Francine and Helene, also underwent rapid intensification. And like Hurricane Helene, Milton has fed upon the exceptionally warm waters that have characterized the Gulf of Mexico this year. Scientists have already determined that climate change increased the severity of the rainfall from Helene and made the warm ocean waters that fueled the storm 200 to 500 times more likely.

Hurricane Milton began as an orderly tropical cyclone. “It’s been a pretty compact hurricane. It had at one point what we call a pinhole eye, which is a really small eye,” says Anantha Aiyyer, an atmospheric scientist at North Carolina State University.

Later, Hurricane Milton completed what scientists dub an eye wall replacement cycle, which caused the storm to weaken some but grow in size. During this process, a storm builds a new eye wall, the strong winds that form the heart that surrounds its existing core. Within a day, the original eye wall can collapse, giving way to the new structure.

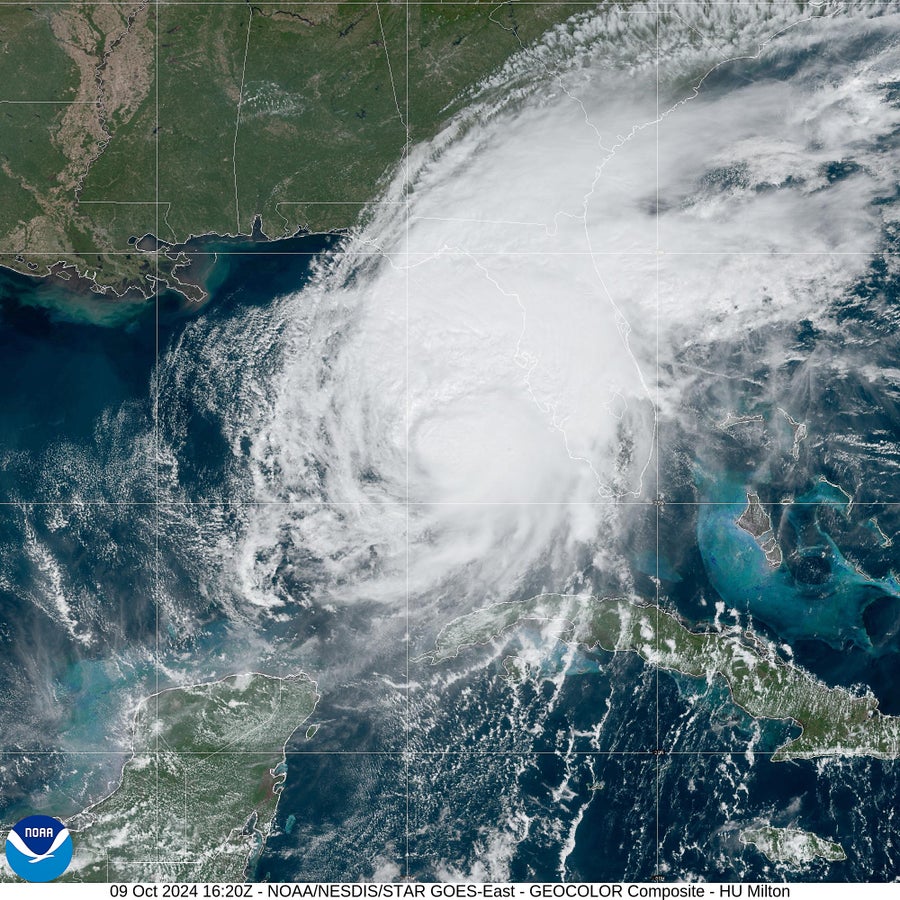

A satellite image shows Hurricane Milton approaching Florida’s western coast over the Gulf of Mexico on October 9, 2024.

CIRA/NOAA/NESDIS/STAR GOES-East

That’s not of academic interest: the eye wall replacement process allows the storm’s clouds—and damage—to cover more ground. “What’s really concerning with these types of eye wall replacement cycles is that the wind field of the storm grows bigger,” Corbosiero says. The National Hurricane Center predicted that Milton’s area of tropical-storm-force winds could double in size between the morning of October 8 and when it reaches Florida.

In the afternoon of October 9, Milton began to encounter additional wind shear, which means that the storm’s structure is being subjected to winds coming from different directions at different speeds. The phenomenon tears at a tropical cyclone, weakening the storm, which occurred with Milton. But that weakening did little to affect the damage forecasts. Further weakening of the storm is forecast as it crosses over land, but considerable damage from winds, surge and torrential rains is expected to continue.

Before making landfall, the storm was also expected to undergo a phenomenon called extratropical transition, which occurs when a hurricane moves out of a tropical atmosphere and begins encountering atmospheric patterns more typical of cooler environments. “You’re transitioning from this more uniform, warm, moist environment to an environment with a lot of contrasts,” says Allison Michaelis, an atmospheric scientist at Northern Illinois University. It’s a common shift for a storm to make as it heads north, although Milton is embarking on it somewhat farther south than many do, she says.

The best example of extratropical transition is Hurricane Sandy in 2012. The phenomenon tends to make hurricanes a little less orderly—their winds tend to weaken, but the storms also typically grow larger, subjecting more land and people to serious wind and rain, Aiyyer and Michaelis say. The process can also shift where the strongest winds occur. “The storm is really adjusting its identity from a tropical storm to an extratropical storm,” Aiyyer says, characterized by a cold core and less symmetric structure.

Hurricane Milton is expected to complete this transition as or after it wraps up its time in Florida, Michaelis says, so the different rainfall patterns of these storm types are not likely to change the impacts people should expect on the ground. And unlike the notorious Hurricane Sandy, Milton doesn’t appear to be headed for any atmospheric flows that could carry it back to land to devastate the East Coast of the U.S. once it exits Florida.

As Milton evolved, it was clear that no atmospheric specifics were likely to significantly change the severity of hazards the region experienced. And Tampa Bay is known to be particularly vulnerable to serious hurricanes, which it typically experiences only peripherally. “We have been brushed by many, many, many, many storms,” Davis says. But the last time a major hurricane made landfall in the region was in 1921. It hasn’t seen a direct hit from any hurricane at all since 1946. Milton could break that trend.

After hitting the west-central coast of Florida, Hurricane Milton is expected to cross the state and then track across the Atlantic Ocean. Parts of coastal Georgia are under a tropical storm warning, meaning that tropical storm conditions are expected within 36 hours. Meanwhile in other parts of Georgia and coastal South Carolina, tropical storm conditions are possible within the coming 48 hours. Bermuda might also see effects over the weekend, although the storm’s more southerly path may spare the island. (On October 7 and 8, before Milton reaches Florida, the storm had been forecast to cause four to six feet of storm surge and two to four inches of rainfall in the Yucatán peninsula.)

In Florida, however, the risks are very real. “I just want people to take this more seriously than they’ve taken any other storm,” Davis says. “This will be a storm that people will not forget.”

Corbosiero echoes that concern, especially given the fact that Milton comes so close on the heels of Helene and its damage. “This really does have the likelihood to be the worst disaster in hurricanes in U.S. history,” she says. “It’s that much of a potential dire situation, especially if it makes a direct hit on Tampa or one of the very populated areas along [Florida’s] west coast.”

Editor’s Note (10/9/24): An earlier version of this story was posted on October 7.