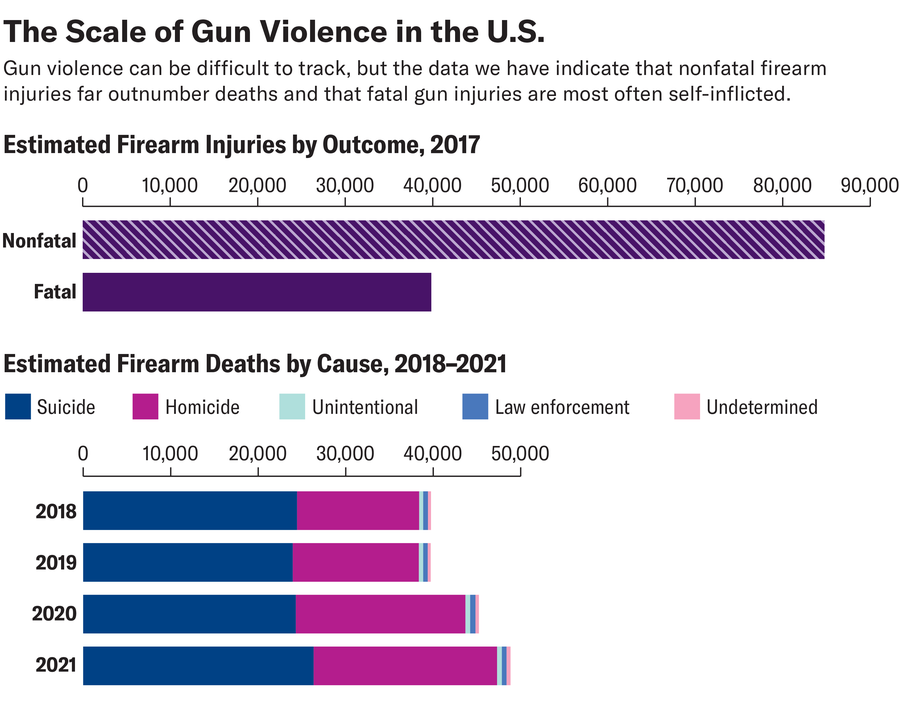

The U.S. is home to more guns than people. The toll of this abundance of firearms is staggering: Guns killed more than 48,000 people in the U.S. in 2022, the equivalent of one person every 11 minutes. More than half of those deaths were suicides, and guns are the overall leading cause of death in children aged one to 17. Mass shootings—600-some per year in recent years, although definitions vary—have stoked fear and anger, reshaping the American school experience. Yet mass shootings make up only a tiny fraction of firearm fatalities. And about a third of Americans say they own a gun, even as six in 10 say they favor stricter gun laws.

Amanda Montañez; Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WISQARS database (death data); Everytown for Gun Safety (nonfatal injury data)

The rage, despair, carelessness and greed behind the deaths may be universal, but such numbers are unique to the U.S. Here “our interpersonal conflicts are much more likely to be lethal because we’re more likely to be armed with guns,” says Daniel Webster, a gun violence researcher at Johns Hopkins University.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

But there’s nothing inevitable about the prevalence of gun deaths in the U.S. It’s a reality that policies have created and that policies could change, if the political will existed. Evidence suggests that if Vice President Kamala Harris were to become the next U.S. president, she would move toward policies that would reduce gun violence—and that if former president Donald Trump were reelected, he would support laxer policies that could permit gun violence to worsen.

Compared with other common health issues in the U.S., data about gun violence are limited; data about nonfatal gun injuries are almost nonexistent. These gaps, combined with the usual scientific difficulties of distinguishing between causation and correlation, mean researchers lack much of the detailed information they need to analyze the effects of different gun-related policies. That said, the existing research does show that more guns do not keep people safer.

Here’s a rundown of what we can expect from each presidential candidate when it comes to gun policy:

Harris on Gun Policy

Harris has a long history of working with gun policy: She did so when she held a string of district attorney offices in the 1990s and 2000s and when she became California’s attorney general in the 2010s. Throughout those periods, she encouraged the development of stricter restrictions on gun ownership, as well as stronger enforcement of existing regulations. Later, as a U.S. senator, Harris worked on legislation to mandate universal background checks and to better regulate gun dealer licensing. She has in the past also called for both a ban on and a mandatory buyback of assault weapons, although Webster says studies suggest that assault weapon bans can be evaded too easily to impact violence rates.

In 2022, during the Biden-Harris administration, Congress passed the first sweeping gun legislation in nearly three decades. This included important funding mechanisms, as well as a few policy changes, such as requiring stronger background checks on gun buyers under 21 years old, requiring more gun sellers to conduct background checks and broadening a measure meant to keep guns away from domestic violence offenders. The latter now include those who have abused dating partners, as well as spouses and close family members.

The single most effective policy to reduce gun deaths, according to Webster’s research, is an independent licensing process for gun ownership—not merely a background check managed by gun dealers themselves—that includes vetting the fingerprints and other information an applicant provides. Webster also finds positive results from regulations that take guns away from domestic violence offenders.

President Joe Biden created a White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention, which Harris oversees and which works on policies at both the state and local levels. “This is the first office of gun violence prevention that was initiated in the White House and overseen by a vice president,” says Joseph Richardson, Jr., a medical anthropologist at the University of Maryland. “I don’t think most Americans are even aware that she runs that office.”

That office and the 2022 legislation both go beyond policies directly related to gun access. For example, Richardson studies community violence intervention programs, which he says have been shown to reduce shootings when they are allowed to operate for at least three to five years.

Both Webster and Rosanna Smart, an economist at the nonprofit think tank RAND and co-director of its Gun Policy in America initiative, say that because U.S. gun violence is related to a wide variety of socioeconomic factors, policies directly related to guns—while crucial in themselves—are not the only necessary step. For example, given that more than half of gun deaths are caused by suicide, reducing fatalities also requires improving living situations and mental health care. Most of all, Webster says, gun violence is about desperate conditions. “It’s not just race; it’s not just poverty. It’s very concentrated disadvantage that really shuts off constrained social networks and opportunities to thrive,” he says.

Harris nods to this broader approach on her campaign website, mentioning gun violence prevention programs in particular.

At campaign rallies she has discussed the damage done by school shootings and active shooter drills. She has also met with survivors of the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting, who are old enough to vote in a presidential election for the first time this year.

Still, some experts say two key policy approaches with demonstrated effects in reducing gun violence, particularly among younger people, seem to be missing from Harris’s campaign. Smart says she has found particularly strong evidence that laws implementing stricter minimum age requirements for purchasing firearms reduce gun suicides in young people. Laws that either make guns less accessible to children or penalize owners if their gun is accessed by a child also reduce all types of gun violence among young people, Smart says.

During the September 10 presidential debate with Trump, Harris pointed to her experience prosecuting gun traffickers—but she also noted that both she and her running mate, Minnesota’s governor Tim Walz, are gun owners, and she said they didn’t intend to take away anyone’s guns. During the vice presidential debate held on October 1, Walz noted that the quest to find causes of gun violence can be distractions. “I think what we end up doing is we start looking for a scapegoat,” he said. “Sometimes it just is the guns.”

Trump on Gun Policy

Trump, meanwhile, has explicitly positioned himself as a friend to gun owners and “defender of the Second Amendment”; his campaign has even set up a “Gun Owners for Trump” web page. As president in 2017–2021, he loosened some restrictions around gun ownership, ensured gun sales could continue during early COVID shutdowns and appointed some 200 federal judges with gun-friendly records.

Yet Trump also banned bump stocks, attachments that allow semiautomatic guns to shoot faster; the Supreme Court, including all three justices appointed by Trump, overturned that rule in June. In 2022 the court overturned a New York State provision limiting concealed carry of weapons, the implications of which are still being determined. Given federal inaction, most gun regulation happens at the state level—but rulings like the one in the New York State case undermine states’ authority, says Garen Wintemute, a physician and chair in violence prevention at the University of California, Davis, who studies gun violence.

Earlier this year Trump spoke at the National Rifle Association’s annual meeting in conjunction with the group’s endorsement of his candidacy. Since then Trump has endured two assassination attempts that involved guns: one at a July campaign rally in Pennsylvania and one in September at his golf course in Florida. These incidents have shown no sign of changing his stance. Trump has also owned firearms, although his felony convictions this spring suspended his right to own guns.

Wintemute says the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol—which came after Trump sowed doubt about his loss in the 2020 election—could have been far deadlier without the existing gun control measures. Although some of the January 6 rioters brought firearms, others chose not to because of Washington, D.C.’s strict gun laws. Wintemute now worries that Trump’s rhetoric about political violence, combined with existing gun regulation (or even potentially weakened restrictions, should Trump win the White House again next month) could have disastrous consequences for democracy in the U.S.

Trump’s running mate, Senator J. D. Vance of Ohio, has called school shootings “a fact of life” and “increasingly the reality we live in.” The official Republican platform calls for “hardening” schools (through steps such as adding physical security and arming teachers), even though some data show this doesn’t reduce gun violence. “We have to make the doors lock better,” Vance said during the vice presidential debate. “We have to make the doors stronger. We’ve got to make the windows stronger.” Additional campaign materials cite diverting student “troublemakers” to correctional facilities, encouraging teachers to carry concealed weapons, and bringing veterans and retired police officers into schools as armed guards.

The 2024 Republican platform also promises to defend constitutional rights, including the right to bear arms, but it doesn’t mention many specific policies an administration would pursue. Project 2025, a 900-page conservative policy blueprint that Trump has denounced, despite the fact that it was written by several key associates of his and Vance’s, also dedicates surprisingly little space to gun policy. It does suggest that Congress should move the agency that oversees firearms out of the Department of Justice and into that of the Treasury—a move that critics say would weaken enforcement of gun policies.

One key policy that Trump has expressed interest in throughout the campaign, and has promised to sign, is concealed carry reciprocity legislation that would erode concealed weapon bans where they do exist. Smart says her research shows that policies permitting concealed guns are associated with higher death rates, as are “stand your ground” laws (the latter permit the use of fatal violence in self-defense without attempting to retreat first).

Overall, a Trump administration would likely do little to address gun violence—and have potentially dangerous long-term consequences stemming from Trump’s reshaping of the courts. In contrast, several of the policies Harris calls for could reduce gun violence, but the effects might not be felt right away, given the current prevalence of guns in the U.S.

IF YOU NEED HELP

If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, help is available. Call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or use the online Lifeline Chat.

Additional reporting by Tanya Lewis.