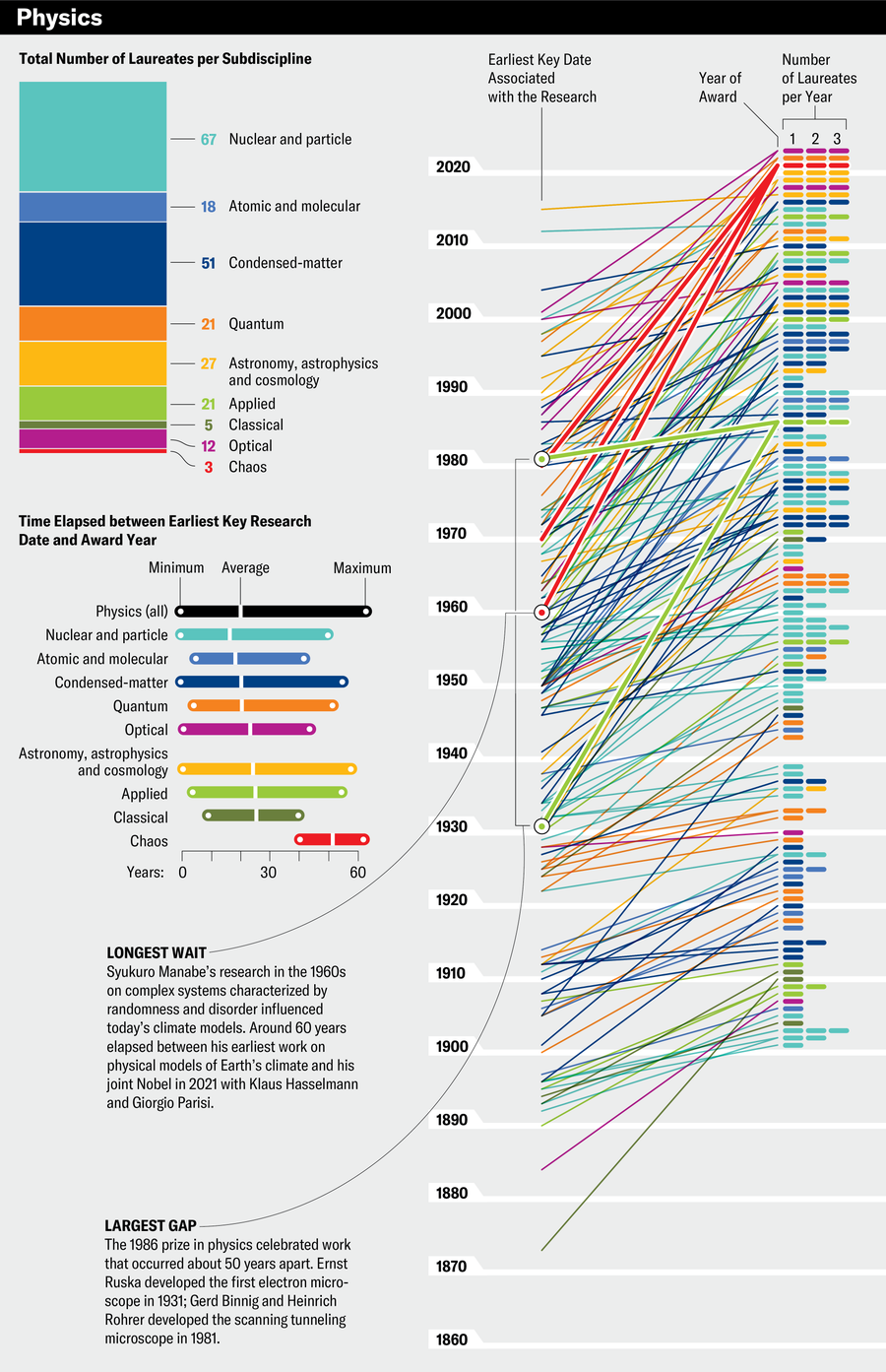

Meteorologist Syukuro Manabe shared the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work modeling gases’ movement through a column of atmospheric air—in the 1960s. His 60-year-old research had proved foundational for the computer models that scientists use today to interpret and predict our changing climate.

Manabe’s wait was particularly long, but there is often a substantial gap between the awarding of a Nobel Prize and the earliest work it honors—an average of 20 years across categories, Scientific American found. “It takes time to prove that something has impact beyond just curiosity,” says John Ioannidis, a Stanford University professor who has examined the Nobels’ distribution and influence. Although the awards are not a representative look at all of science, they reveal the trends and incentives shaping key scientific fields.

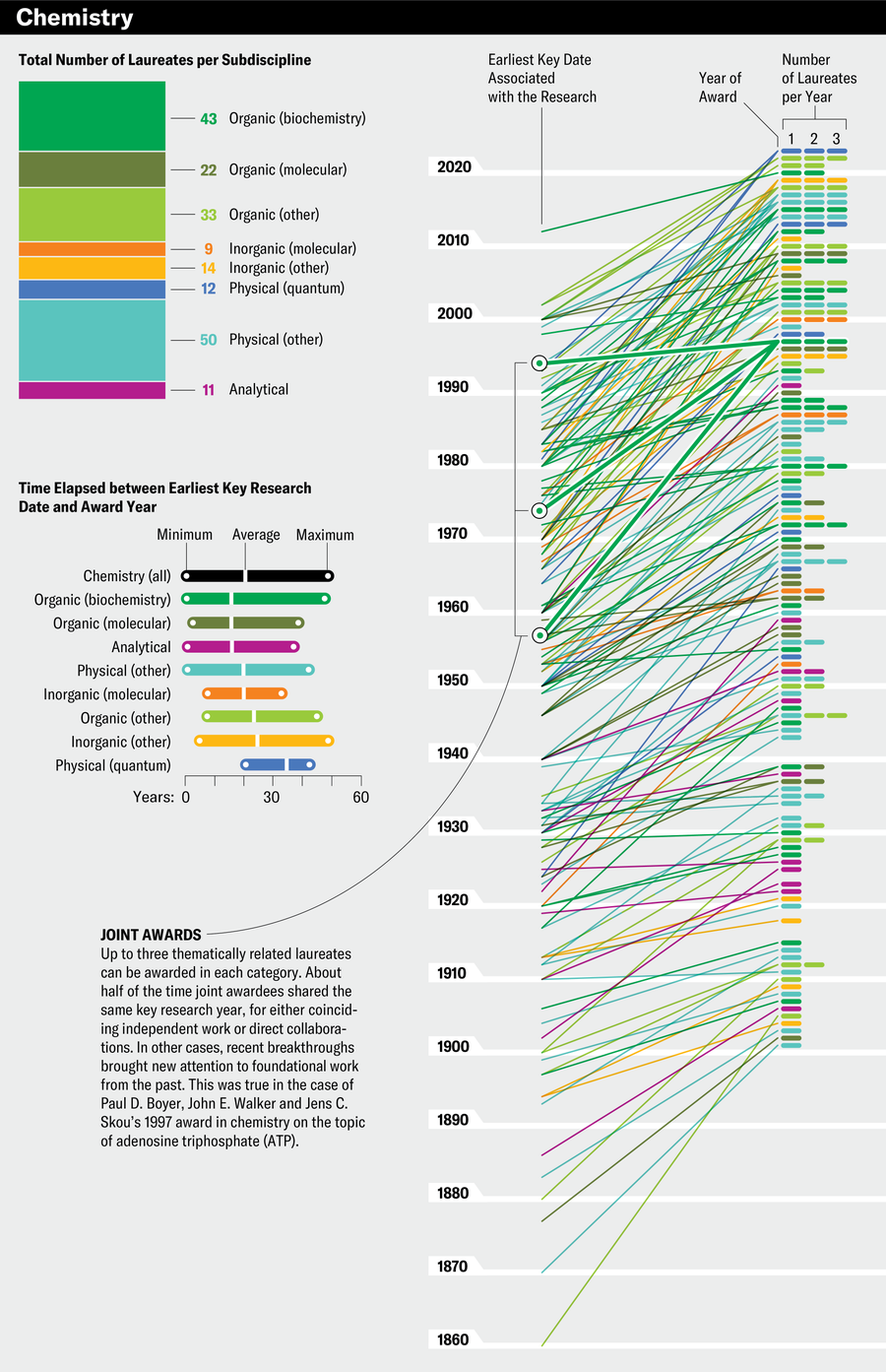

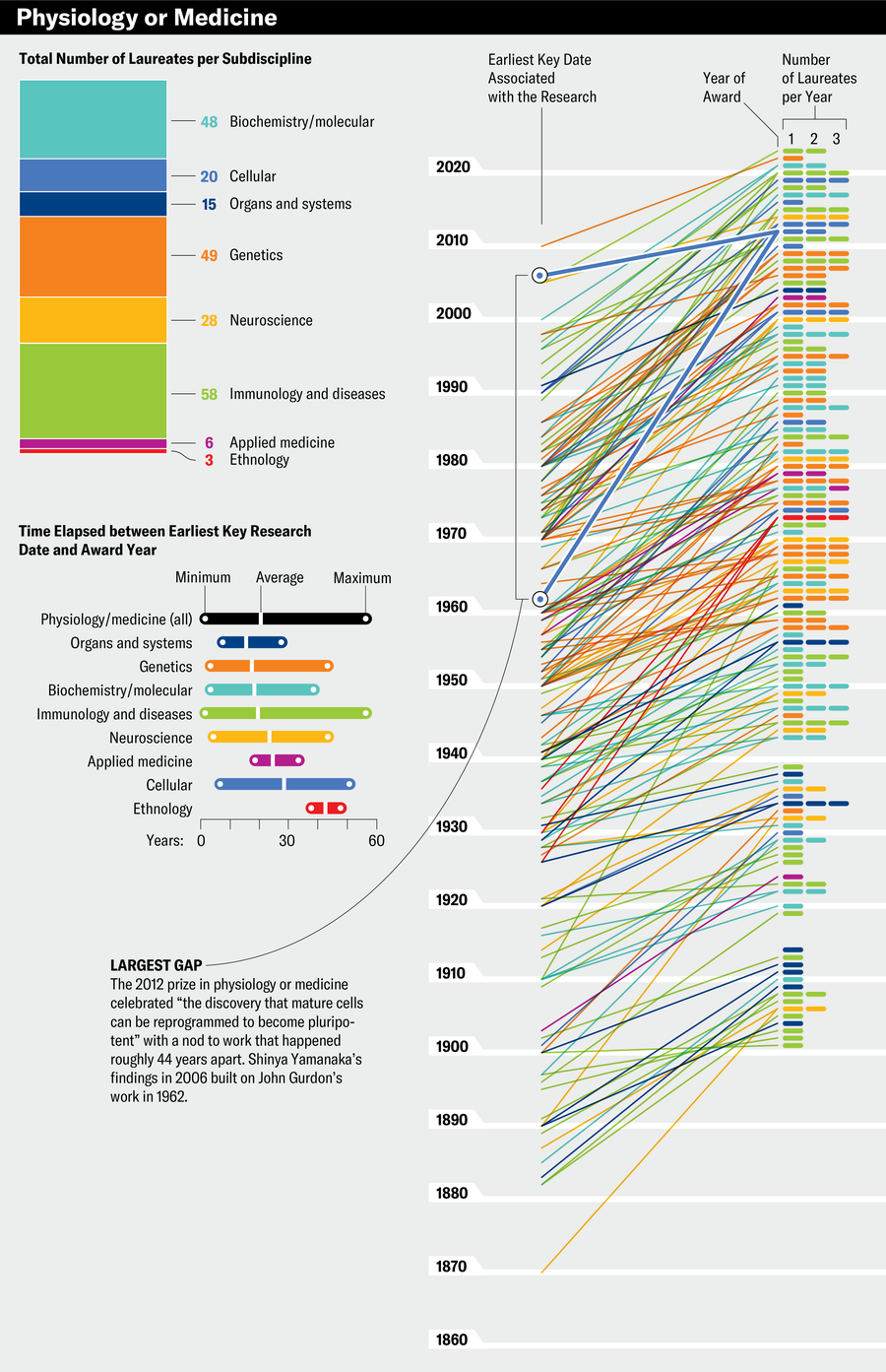

As Nobel season approaches, we at the magazine wondered what subfields of science have been most celebrated and whether there are visible patterns related to the amount of time between the research and the recognition. We used the official Nobel synopses and statements to sort the awards into our own subdiscipline categories and to inform research dates on a timeline that shows the trends.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

One clear pattern is the increase in multiple laureates per prize. Each award can be split among a maximum of three living researchers, but that rule is increasingly constraining as science becomes more collaborative. This stipulation may even skew what gets highlighted as the most significant research going forward, Ioannidis suggests, if a Nobel Committee cannot pick only three individuals responsible for a result. “It’s not easy to have someone who really stands out so separately from the rest of the world.”

Jen Christiansen; Source: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/lists/all-nobel-prizes/all/ (primary reference)

Jen Christiansen; Source: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/lists/all-nobel-prizes/all/ (primary reference)

Jen Christiansen; Source: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/lists/all-nobel-prizes/all/ (primary reference)