The future of ground-based astronomy is bright. And that’s bad.

The sky is rapidly filling with fast-moving satellites reflecting sunlight and zapping astronomers’ detectors. It is, after all, exceedingly difficult to see faint galaxies in the distant cosmos when someone is shining a flashlight down your telescope.

The biggest culprit is SpaceX, which has launched a massive and growing fleet of Starlink Internet satellites since 2018. Of the more than 7,500 total working satellites in orbit around the Earth, over 3,900 are Starlinks—meaning more than half of the birds circling our planet fly the SpaceX flag.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

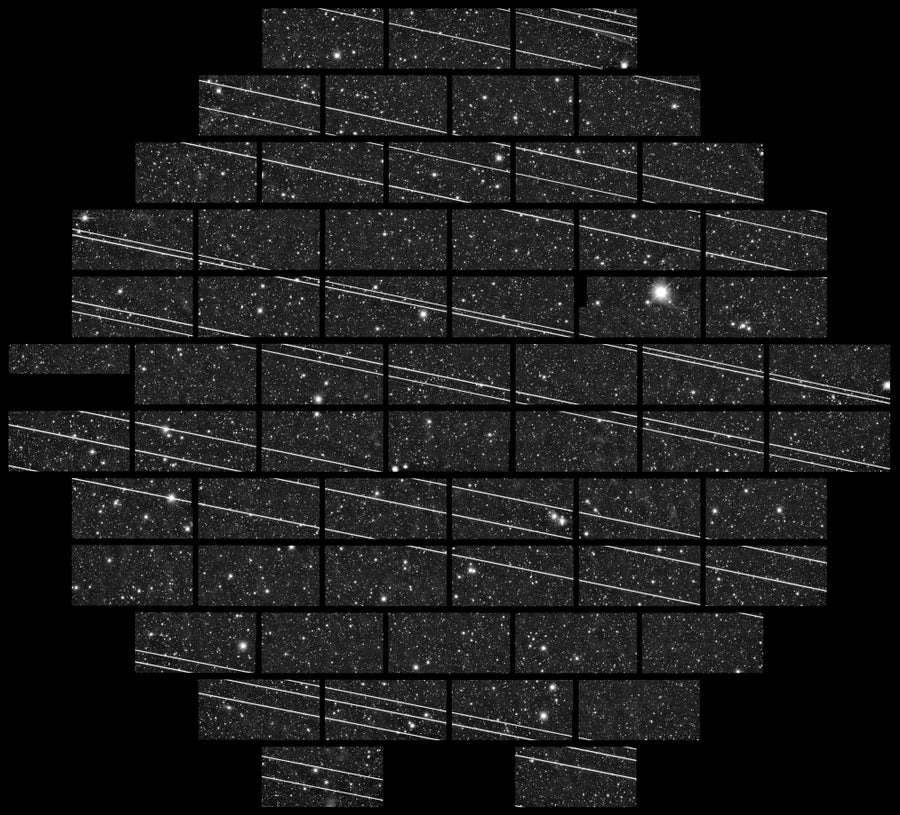

These satellites are already menacing astronomy. Many telescopes, especially those doing wide-angle surveys of the sky to search for Earth-threatening asteroids, are seeing observations ruined by bright satellites streaking across their field of view. If not caught, these can cause false positives: things at first assumed to be real but that can take exhaustive efforts to discover are not. This will only get worse as more Starlinks are flown; 12,000 are planned, and SpaceX has filed paperwork for an additional 30,000 beyond that. If this comes to pass, the sky will be filled with satellites zipping across it.

An image from the Dark Energy Camera mounted on a 4-meter telescope in Chile shows 19 streaks from Starlink satellites, despite an exposure time of only 5.5 minutes. Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/DECam DELVE Survey (CC BY 4.0)

But, in a potential irony, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk has claimed that the cause of this woe may also be its cure. The company is currently testing its huge Starship rocket, which, if it works as planned, will have the capability to launch extremely large and heavy payloads. This, Musk said, can be used to send large telescopes into space above the fleet of Starlink satellites, potentially alleviating the contamination issue and ushering in a new era of widespread space-based astronomy.

Historically, Musk has made a lot of claims over a wide range of topics that didn’t—or cannot—pan out. His flawed hyperloop plan, for example, or nuking the Martian poles to create an atmosphere, or basically anything he’s promised about Twitter. These claims, in general, are more than just unrealistic; they also lack any of the specificity necessary to actually carry them out.

The same is true for his idea of a revolution in space-based astronomy. This claim is (to be generous) naive. Like many such claims it feels right, but doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. In a nutshell, while there are definite and wonderful things Starship can do for astronomy, it’s not by any means a catch-all solution to the Starlink problem.

A lot of cutting-edge astronomy is done with very large telescopes, some with mirrors eight or more meters across. At the moment, no rocket is capable of launching a monolithic mirror that size into space.

Both the American Delta IV Heavy and the European Ariane 5 rockets have a payload fairing—the part at the top of the rocket that encloses a would-be space telescope—with an inner diameter of about five meters. These are two of the largest rockets flying, but unfortunately both are being retired (and the planned next-generation Ariane 6 is having some development issues). Neither is large enough to house the biggest telescopes anyway.

NASA’s huge Space Launch System currently has a similarly sized fairing, and a future planned configuration can fling a whopping 130 tons to orbit with a working fairing diameter of about nine meters. However, its launch costs are prohibitively expensive, easily topping $2 billion.

Starship has a current fairing width of about eight meters (a future version would span ten meters), and a maximum length of about 17 meters. It will loft 100 tons to low-Earth orbit. That’s roomy enough to house a big telescope. While it’s not clear how much a Starship launch will cost, something under $100 million is not unreasonable. At a press conference in February 2022 Musk said that in a few years the cost might come down to as little as $10 million, but again his claims should be taken with a Mars-sized lump of salt.

Clearly Starship can lower the launch cost considerably. However, for most space telescopes, especially large ones, launch costs are not a huge fraction of their lifetime costs. Hubble, for example, has cost north of $16 billion (in 2021 dollars) over the years, and its space shuttle launch was about a billion dollars. JWST has a projected price tag of about the same amount, with a launch cost of about $200 million.

Lowering launch costs would be nice, but it’s only a dent in the budget. Most of the money is spent on developing and building the telescope, because operating in space is far more difficult than on the ground, multiplying the overall cost by an order of magnitude; for example the much larger twin 10-meter Keck telescopes in Hawaii cost about $90 million (in 1991 dollars) each.

To be fair, some of that enormous development price tag for space telescopes is because, at the moment, a big telescope has to fit in a smaller fairing. JWST was tucked into the Ariane 5 fairing folded up and had to unfold in space like a 10 gigabuck origami experiment, something never been done before that added hugely to the cost. A bigger fairing would have precluded that (though, it should be noted, the tennis-court-sized sunshield necessary to keep the infrared telescope cold still needed to be folded up to fit). Also, Starship’s heavier weight limit would mean engineers need not shave every ounce they could off the telescope; sturdier, heavier framing could be used at much lower cost.

But—and this is a very big but indeed—it also costs a lot of money to run a space telescope. Ground operations for Hubble run about $100 million per year, and JWST is $172 million annually. The Keck telescopes only cost $16 million. Clearly, the added expense of just using a space telescope quickly outpaces any savings in launch cost.

Musk’s astronomical revolution claim also doesn’t account for the many dozens of smaller telescopes on the ground still having a large impact on astronomy. These are far less expensive to build and operate; many major universities have one, or buy into a consortium like the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy to use the telescopes they manage. Tens of thousands of Starlink satellites will degrade their observations. Replacing them with space-based telescopes isn’t reasonable or feasible.

There is clearly a very exciting future for astronomy in space, assuming Starship works as promised (the first test flight had some serious issues; the loss of the vehicle wasn’t unexpected, but it’s not clear yet if that was a result of it simply being an untested rocket or if some serious design and launch flaws doomed it). However, Starship is a double-edged sword, capable of launching big telescopes but also deploying vast numbers of Starlink satellites.

Space telescopes were never meant to replace ground-based observatories, nor can they. They work together, complementarily, but we need both. Whatever benefits Starship provides for telescopes, it is literally not the one-size-fits-all solution to the growing Starlink problem.

Author’s Note: My thanks to astronomer and “orbital cop” Jonathan McDowell for his help with some of the numbers in this article.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.