Somebody hit the warp speed button, judging from the icy wings astronomers have spotted surrounding an approaching comet.

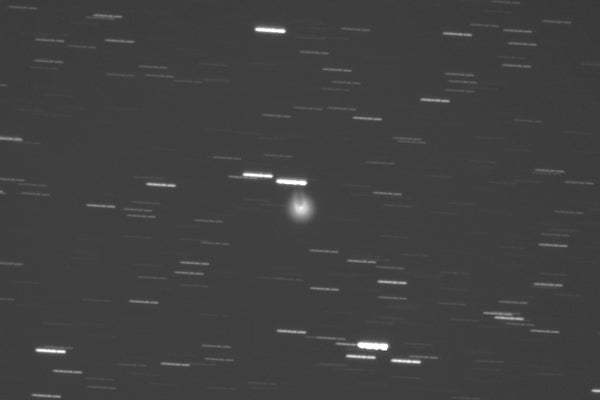

Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, which has been likened to the Millennium Falcon of Star Wars fame by one astronomy website for its new look, is now inbound on a fast pass by the sun. It’s one of the brightest known Halley–like comets, which are icy rocks that take 20 to 200 years to orbit the sun and do so along a steeply inclined path relative to the rest of the solar system. On July 20 astronomers worldwide spotted its outburst when the comet brightened 100-fold, making it visible as a horseshoe-shaped aura in backyard telescopes. The outburst may result from a rare case of icy volcanism on a comet—uncorked by solar heating of volatile gases trapped under cometary crusts. Sunlight reflecting off the tossed-up material on the comet’s surface is what causes the brightening.

“Comets are known to be unpredictable,” says astronomer Gianluca Masi of the Virtual Telescope Project, which is a network of worldwide robotic telescopes. “A few of them are famous just for these outbursts.” For instance, in 2021 Comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann erupted four times back-to-back in such a spectacular show that some astronomers referred to it as a “super outburst.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Masi speculates Comet Pons-Brooks’s horseshoe shape may result from shadows cast by the dusty “coma” swathing the object after the outburst. “This is not happening every night, so these are precious opportunities,” Masi adds, referring to the fact that astronomers can learn more about these cosmic snowballs and our own space neighborhood. Made of dust, rock and ice, comets are the frozen leftovers from the formation of our solar system.

The comet’s outburst has tossed perhaps 10 billion kilograms of dust and ice into space, which is “fairly large,” says astronomer Carrie Holt of the University of Maryland. Although outbursts have been spotted from the comet by astronomers for centuries, she called the shape of its latest one, “quite peculiar,” and said more observations as it draws closer to the sun should help explain its unusual horns.

Comet Pons-Brooks circles the sun once every 71 years, and its closest solar approach will be next year. It will come nearest to Earth in June 2024, when it will pass some 144 million miles from our blue dot. That should make it faintly visible to the naked eye at night. Right now the comet is still beyond the orbit of Mars. That means it will get hotter as it plunges closer to the sun. “Perhaps we will see more fireworks,” Masi says.