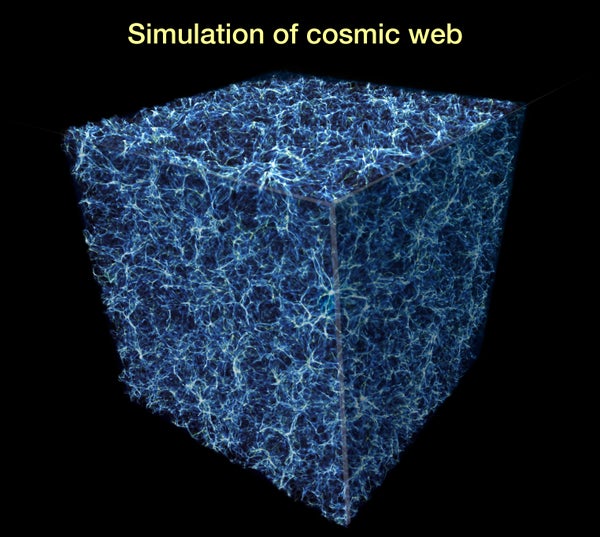

Peer into the sky through a powerful telescope, and beyond the glare of the Milky Way, you can make out the faint glow of distant galaxies. These galaxies clump together in dense clusters joined by wispy filaments and separated by enormous voids hundreds of millions of light-years across. Since the 1980s, scientists have observed millions of galaxies to map this “cosmic web” in ever greater detail in their quest to understand our universe’s history.

But there is more to this large-scale structure than meets the eye. Hydrogen atoms naturally emit radio waves with a characteristic 21-centimeter wavelength, and because hydrogen gas clouds tend to gravitationally cluster around galaxies, patterns in this radio emission reflect matter’s underlying cosmic distribution. In a recent preprint paper, radio astronomers working on the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME) report their first detection of these telltale patterns.

The result is an important first step toward a full map of the cosmic web using hydrogen’s radio emissions, although CHIME’s measurements have yet to reach the precision of state-of-the-art infrared and optical surveys charting large-scale structure. “It’s not the ‘holy grail’ result yet, but it’s a milestone for CHIME and also for the field,” says Tzu-Ching Chang, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who was not involved in the work.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Uncharted Space

In the universe’s “dark ages,” the few hundred million years after protons and electrons first combined to form atoms following the big bang, no stars existed to illuminate all the hydrogen gas then suffusing space. That gas grew denser in some places and more rarefied in others as the tug of gravity competed with cosmic expansion, and the densest regions eventually gave birth to luminous stars, galaxies and galaxy clusters.

By the 1990s, cosmologists thought they understood the broad strokes of this story. So they were shocked to discover in 1998 that cosmic expansion began mysteriously speeding up around five billion years ago, after more than eight billion years of contented coasting. Next to nothing is known about the “dark energy” responsible for this acceleration; one important open question is whether it is an immutable “cosmological constant” or rather a dynamic field with a strength that changes over time.

Maps of the cosmic web may point toward an answer. Light from more distant galaxies takes longer to reach us, and the expansion of the universe stretches the wavelength of this ancient light toward the red end of the visible spectrum: the more distant the galaxy, the larger the cosmic redshift. Precise redshift measurements, based on the unique spectral fingerprints of atoms that are abundant within galaxies, thus allow astronomers to construct three-dimensional maps of the cosmic web. These maps encode a wealth of information about the history of cosmic expansion and the evolution of large-scale structure.

The most recent completed galaxy survey, called the Extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (eBOSS), cataloged the positions and redshifts of half a million galaxies and as many quasars—extremely bright regions at the cores of large galaxies powered by supermassive black holes. The eBOSS team then used this catalog to construct a map that covers about 15 percent of the sky and stretches back more than 11 billion years. And even more ambitious follow-up surveys are underway.

A New Hope

Yet despite their successes, galaxy surveys have their limitations. Telescopes must first scan the sky to select galaxies to include in the survey, and subsequent measurements of individual galaxy redshifts tend to be time-consuming. State-of-the-art surveys also demand expensive spectrometers with thousands of moving parts.

Hydrogen intensity mapping, the strategy pursued by CHIME, could prove a cheaper and faster way to map the cosmos. 21-cm radio waves from distant gas clouds get redshifted just like visible light. But radio telescopes can measure how the intensity of radio emission varies across the sky at many different wavelengths at once, enabling astronomers to construct three-dimensional maps without separate redshift measurements. Dedicated intensity mapping telescopes are also inexpensive, “an order of magnitude cheaper than comparable spectroscopic instruments in optical or infrared,” says Kavilan Moodley, a professor of astronomy at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, who is not affiliated with CHIME.

Intensity mapping faces its own challenges. The main difficulty is that the cosmological signal is small, and the Milky Way itself is a strong radio emitter. “You’re trying to look behind it at something which is 1,000 or 10,000 times fainter,” Moodley says. Teasing out the imprint of the cosmic web requires precise telescope modeling and careful analysis.

CHIME is a row of four radio telescopes with no moving parts, each resembling a snowboarding half-pipe made of chicken wire. As Earth rotates, the telescopes sweep out a low-resolution map of the entire northern hemisphere. The resulting 3-D map is composed of “voxels” rather than “pixels,” with each voxel roughly 30 million light-years on a side, 10 million light-years deep and typically filled with hundreds of galaxies. That coarse spatial resolution is a feature, not a bug: adding up the radio emission from all the hydrogen in each voxel allows astronomers to pick up faint signals they would not otherwise see. And because the effects of dark energy are most pronounced at very large distance scales, the structure within individual voxels is irrelevant for these studies.

In 2009 and 2010 Chang and other astronomers found the first traces of the cosmic web in hydrogen’s 21-cm emission using radio telescopes in Australia and West Virginia. But these telescopes are 100-meter dishes that collect light from a small region of the sky, so they could not efficiently map the large areas necessary for a more complete view. These facilities are also in high demand, and only a fraction of their observations can be devoted to 21-cm observations. The new CHIME results, derived from data collected in 2019, are the first from a radio telescope that was specifically designed to map the cosmic web. This allowed the CHIME researchers to better control systematic errors, and they did not have to compete with other astronomers for telescope time. The project’s data go back as far as nine billion years, a billion years deeper into the past than previous radio measurements.

The First Signal—But Not the Last

After processing their data to remove foreground emission from the Milky Way and terrestrial sources, the researchers used a technique called “stacking” to study the correlations between CHIME’s data and galaxy maps from the eBOSS survey. They saw an unmistakable signal: the regions of more intense radio emission overlapped with the positions of known galaxies and quasars. “When you have that first detection, it’s enormously motivating,” says Seth Siegel, a research scientist at McGill University and one of the leaders of the CHIME team’s analysis. The result is an important milestone, he says, because it gives the CHIME researchers a baseline from which they can pursue further improvements.

The team is now working on using more recent CHIME data to construct a stand-alone map, without the aid of the eBOSS catalog. It then plans to search for correlations in the distribution of hydrogen gas on longer distance scales, for which teasing apart the signal from foreground emission becomes especially challenging. Such correlations are the vestiges of sound waves—called “baryon acoustic oscillations” by cosmologists—that rippled through the fiery primordial plasma that filled the early universe. The characteristic scale of these oscillations—roughly 500 million light-years in the present-day universe—has been measured precisely using other methods. Thus, baryon acoustic oscillations can serve as a sort of yardstick that the team can use to measure other distances in its maps in search of deviations from standard cosmology, such as changes in the strength of dark energy.

Richard Shaw, a research scientist at the University of British Columbia, who co-led the analysis with Siegel, emphasizes that this is just the beginning for CHIME. “We have bags of data in the can and more coming,” he says.