Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in Spektrum der Wissenschaft, Scientific American’s sister publication, as “Digitale Demokratie statt Datendiktatur.”

“Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another.”

—Immanuel Kant, “What is Enlightenment?” (1784)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

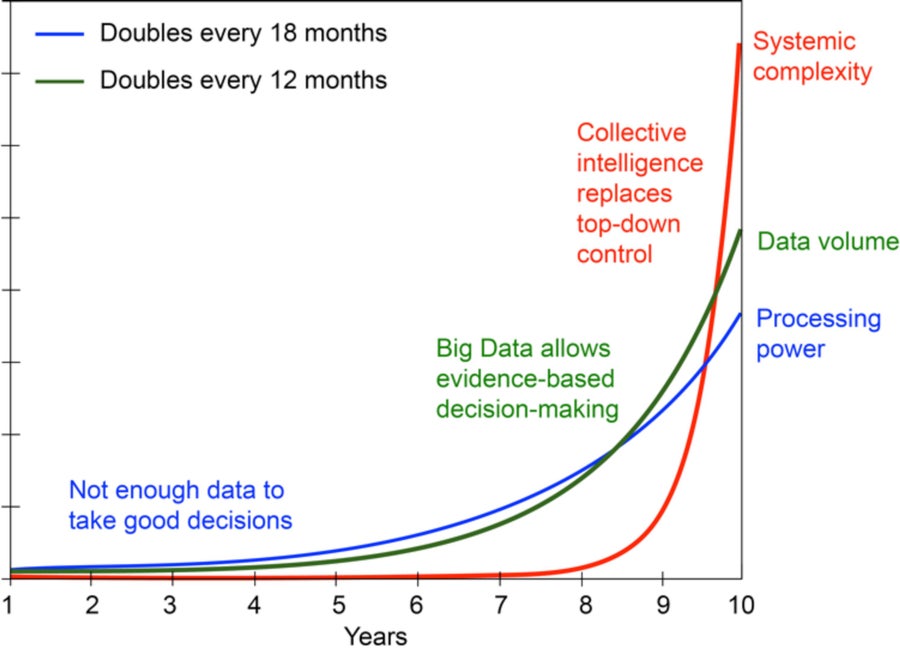

The digital revolution is in full swing. How will it change our world? The amount of data we produce doubles every year. In other words: in 2016 we produced as much data as in the entire history of humankind through 2015. Every minute we produce hundreds of thousands of Google searches and Facebook posts. These contain information that reveals how we think and feel. Soon, the things around us, possibly even our clothing, also will be connected with the Internet. It is estimated that in 10 years’ time there will be 150 billion networked measuring sensors, 20 times more than people on Earth. Then, the amount of data will double every 12 hours. Many companies are already trying to turn this Big Data into Big Money.

Everything will become intelligent; soon we will not only have smart phones, but also smart homes, smart factories and smart cities. Should we also expect these developments to result in smart nations and a smarter planet?

The field of artificial intelligence is, indeed, making breathtaking advances. In particular, it is contributing to the automation of data analysis. Artificial intelligence is no longer programmed line by line, but is now capable of learning, thereby continuously developing itself. Recently, Google's DeepMind algorithm taught itself how to win 49 Atari games. Algorithms can now recognize handwritten language and patterns almost as well as humans and even complete some tasks better than them. They are able to describe the contents of photos and videos. Today 70% of all financial transactions are performed by algorithms. News content is, in part, automatically generated. This all has radical economic consequences: in the coming 10 to 20 years around half of today's jobs will be threatened by algorithms. 40% of today's top 500 companies will have vanished in a decade.

It can be expected that supercomputers will soon surpass human capabilities in almost all areas—somewhere between 2020 and 2060. Experts are starting to ring alarm bells. Technology visionaries, such as Elon Musk from Tesla Motors, Bill Gates from Microsoft and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, are warning that super-intelligence is a serious danger for humanity, possibly even more dangerous than nuclear weapons.

Is This Alarmism?

One thing is clear: the way in which we organize the economy and society will change fundamentally. We are experiencing the largest transformation since the end of the Second World War; after the automation of production and the creation of self-driving cars the automation of society is next. With this, society is at a crossroads, which promises great opportunities, but also considerable risks. If we take the wrong decisions it could threaten our greatest historical achievements.

In the 1940s, the American mathematician Norbert Wiener (1894–1964) invented cybernetics. According to him, the behavior of systems could be controlled by the means of suitable feedbacks. Very soon, some researchers imagined controlling the economy and society according to this basic principle, but the necessary technology was not available at that time.

Today, Singapore is seen as a perfect example of a data-controlled society. What started as a program to protect its citizens from terrorism has ended up influencing economic and immigration policy, the property market and school curricula. China is taking a similar route. Recently, Baidu, the Chinese equivalent of Google, invited the military to take part in the China Brain Project. It involves running so-called deep learning algorithms over the search engine data collected about its users. Beyond this, a kind of social control is also planned. According to recent reports, every Chinese citizen will receive a so-called ”Citizen Score”, which will determine under what conditions they may get loans, jobs, or travel visa to other countries. This kind of individual monitoring would include people’s Internet surfing and the behavior of their social contacts (see ”Spotlight on China”).

With consumers facing increasingly frequent credit checks and some online shops experimenting with personalized prices, we are on a similar path in the West. It is also increasingly clear that we are all in the focus of institutional surveillance. This was revealed in 2015 when details of the British secret service's "Karma Police" program became public, showing the comprehensive screening of everyone's Internet use. Is Big Brother now becoming a reality?

Programmed Society, Programmed citizens

Everything started quite harmlessly. Search engines and recommendation platforms began to offer us personalised suggestions for products and services. This information is based on personal and meta-data that has been gathered from previous searches, purchases and mobility behaviour, as well as social interactions. While officially, the identity of the user is protected, it can, in practice, be inferred quite easily. Today, algorithms know pretty well what we do, what we think and how we feel—possibly even better than our friends and family or even ourselves. Often the recommendations we are offered fit so well that the resulting decisions feel as if they were our own, even though they are actually not our decisions. In fact, we are being remotely controlled ever more successfully in this manner. The more is known about us, the less likely our choices are to be free and not predetermined by others.

But it won't stop there. Some software platforms are moving towards “persuasive computing.” In the future, using sophisticated manipulation technologies, these platforms will be able to steer us through entire courses of action, be it for the execution of complex work processes or to generate free content for Internet platforms, from which corporations earn billions. The trend goes from programming computers to programming people.

These technologies are also becoming increasingly popular in the world of politics. Under the label of “nudging,” and on massive scale, governments are trying to steer citizens towards healthier or more environmentally friendly behaviour by means of a "nudge"—a modern form of paternalism. The new, caring government is not only interested in what we do, but also wants to make sure that we do the things that it considers to be right. The magic phrase is "big nudging", which is the combination of big data with nudging. To many, this appears to be a sort of digital scepter that allows one to govern the masses efficiently, without having to involve citizens in democratic processes. Could this overcome vested interests and optimize the course of the world? If so, then citizens could be governed by a data-empowered “wise king”, who would be able to produce desired economic and social outcomes almost as if with a digital magic wand.

Pre-Programmed Catastrophes

But one look at the relevant scientific literature shows that attempts to control opinions, in the sense of their "optimization", are doomed to fail because of the complexity of the problem. The dynamics of the formation of opinions are full of surprises. Nobody knows how the digital magic wand, that is to say the manipulative nudging technique, should best be used. What would have been the right or wrong measure often is apparent only afterwards. During the German swine flu epidemic in 2009, for example, everybody was encouraged to go for vaccination. However, we now know that a certain percentage of those who received the immunization were affected by an unusual disease, narcolepsy. Fortunately, there were not more people who chose to get vaccinated!

Another example is the recent attempt of health insurance providers to encourage increased exercise by handing out smart fitness bracelets, with the aim of reducing the amount of cardiovascular disease in the population; but in the end, this might result in more hip operations. In a complex system, such as society, an improvement in one area almost inevitably leads to deterioration in another. Thus, large-scale interventions can sometimes prove to be massive mistakes.

Regardless of this, criminals, terrorists and extremists will try and manage to take control of the digital magic wand sooner or later—perhaps even without us noticing. Almost all companies and institutions have already been hacked, even the Pentagon, the White House, and the NSA.

A further problem arises when adequate transparency and democratic control are lacking: the erosion of the system from the inside. Search algorithms and recommendation systems can be influenced. Companies can bid on certain combinations of words to gain more favourable results. Governments are probably able to influence the outcomes too. During elections, they might nudge undecided voters towards supporting them—a manipulation that would be hard to detect. Therefore, whoever controls this technology can win elections—by nudging themselves to power.

This problem is exacerbated by the fact that, in many countries, a single search engine or social media platform has a predominant market share. It could decisively influence the public and interfere with these countries remotely. Even though the European Court of Justice judgment made on 6th October 2015 limits the unrestrained export of European data, the underlying problem still has not been solved within Europe, and even less so elsewhere.

What undesirable side effects can we expect? In order for manipulation to stay unnoticed, it takes a so-called resonance effect—suggestions that are sufficiently customized to each individual. In this way, local trends are gradually reinforced by repetition, leading all the way to the "filter bubble" or "echo chamber effect": in the end, all you might get is your own opinions reflected back at you. This causes social polarization, resulting in the formation of separate groups that no longer understand each other and find themselves increasingly at conflict with one another. In this way, personalized information can unintentionally destroy social cohesion. This can be currently observed in American politics, where Democrats and Republicans are increasingly drifting apart, so that political compromises become almost impossible. The result is a fragmentation, possibly even a disintegration, of society.

Owing to the resonance effect, a large-scale change of opinion in society can be only produced slowly and gradually. The effects occur with a time lag, but, also, they cannot be easily undone. It is possible, for example, that resentment against minorities or migrants get out of control; too much national sentiment can cause discrimination, extremism and conflict.

Perhaps even more significant is the fact that manipulative methods change the way we make our decisions. They override the otherwise relevant cultural and social cues, at least temporarily. In summary, the large-scale use of manipulative methods could cause serious social damage, including the brutalization of behavior in the digital world. Who should be held responsible for this?

Legal Issues

This raises legal issues that, given the huge fines against tobacco companies, banks, IT and automotive companies over the past few years, should not be ignored. But which laws, if any, might be violated? First of all, it is clear that manipulative technologies restrict the freedom of choice. If the remote control of our behaviour worked perfectly, we would essentially be digital slaves, because we would only execute decisions that were actually made by others before. Of course, manipulative technologies are only partly effective. Nevertheless, our freedom is disappearing slowly, but surely—in fact, slowly enough that there has been little resistance from the population, so far.

The insights of the great enlightener Immanuel Kant seem to be highly relevant here. Among other things, he noted that a state that attempts to determine the happiness of its citizens is a despot. However, the right of individual self-development can only be exercised by those who have control over their lives, which presupposes informational self-determination. This is about nothing less than our most important constitutional rights. A democracy cannot work well unless those rights are respected. If they are constrained, this undermines our constitution, our society and the state.

As manipulative technologies such as big nudging function in a similar way to personalized advertising, other laws are affected too. Advertisements must be marked as such and must not be misleading. They are also not allowed to utilize certain psychological tricks such as subliminal stimuli. This is why it is prohibited to show a soft drink in a film for a split-second, because then the advertising is not consciously perceptible while it may still have a subconscious effect. Furthermore, the current widespread collection and processing of personal data is certainly not compatible with the applicable data protection laws in European countries and elsewhere.

Finally, the legality of personalized pricing is questionable, because it could be a misuse of insider information. Other relevant aspects are possible breaches of the principles of equality and non-discrimination—and of competition laws, as free market access and price transparency are no longer guaranteed. The situation is comparable to businesses that sell their products cheaper in other countries, but try to prevent purchases via these countries. Such cases have resulted in high punitive fines in the past.

Personalized advertising and pricing cannot be compared to classical advertising or discount coupons, as the latter are non-specific and also do not invade our privacy with the goal to take advantage of our psychological weaknesses and knock out our critical thinking.

Furthermore, let us not forget that, in the academic world, even harmless decision experiments are considered to be experiments with human subjects, which would have to be approved by a publicly accountable ethics committee. In each and every case the persons concerned are required to give their informed consent. In contrast, a single click to confirm that we agree with the contents of a hundred-page “terms of use” agreement (which is the case these days for many information platforms) is woefully inadequate.

Nonetheless, experiments with manipulative technologies, such as nudging, are performed with millions of people, without informing them, without transparency and without ethical constraints. Even large social networks like Facebook or online dating platforms such as OkCupid have already publicly admitted to undertaking these kinds of social experiments. If we want to avoid irresponsible research on humans and society (just think of the involvement of psychologists in the torture scandals of the recent past), then we urgently need to impose high standards, especially scientific quality criteria and a code of conduct similar to the Hippocratic Oath.Has our thinking, our freedom, our democracy been hacked?

Let us suppose there was a super-intelligent machine with godlike knowledge and superhuman abilities: would we follow its instructions? This seems possible. But if we did that, then the warnings expressed by Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Steve Wozniak, Stephen Hawking and others would have become true: computers would have taken control of the world. We must be clear that a super-intelligence could also make mistakes, lie, pursue selfish interests or be manipulated. Above all, it could not be compared with the distributed, collective intelligence of the entire population.

The idea of replacing the thinking of all citizens by a computer cluster would be absurd, because that would dramatically lower the diversity and quality of the solutions achievable. It is already clear that the problems of the world have not decreased despite the recent flood of data and the use of personalized information—on the contrary! World peace is fragile. The long-term change in the climate could lead to the greatest loss of species since the extinction of dinosaurs. We are also far from having overcome the financial crisis and its impact on the economy. Cyber-crime is estimated to cause an annual loss of 3 trillion dollars. States and terrorists are preparing for cyberwarfare.

In a rapidly changing world a super-intelligence can never make perfect decisions (see Fig. 1): systemic complexity is increasing faster than data volumes, which are growing faster than the ability to process them, and data transfer rates are limited. This results in disregarding local knowledge and facts, which are important to reach good solutions. Distributed, local control methods are often superior to centralized approaches, especially in complex systems whose behaviors are highly variable, hardly predictable and not capable of real-time optimization. This is already true for traffic control in cities, but even more so for the social and economic systems of our highly networked, globalized world.

Furthermore, there is a danger that the manipulation of decisions by powerful algorithms undermines the basis of "collective intelligence," which can flexibly adapt to the challenges of our complex world. For collective intelligence to work, information searches and decision-making by individuals must occur independently. If our judgments and decisions are predetermined by algorithms, however, this truly leads to a brainwashing of the people. Intelligent beings are downgraded to mere receivers of commands, who automatically respond to stimuli.

In other words: personalized information builds a "filter bubble" around us, a kind of digital prison for our thinking. How could creativity and thinking "out of the box" be possible under such conditions? Ultimately, a centralized system of technocratic behavioral and social control using a super-intelligent information system would result in a new form of dictatorship. Therefore, the top-down controlled society, which comes under the banner of "liberal paternalism," is in principle nothing else than a totalitarian regime with a rosy cover.

In fact, big nudging aims to bring the actions of many people into line, and to manipulate their perspectives and decisions. This puts it in the arena of propaganda and the targeted incapacitation of the citizen by behavioral control. We expect that the consequences would be fatal in the long term, especially when considering the above-mentioned effect of undermining culture.

A Better Digital Society Is Possible

Despite fierce global competition, democracies would be wise not to cast the achievements of many centuries overboard. In contrast to other political regimes, Western democracies have the advantage that they have already learned to deal with pluralism and diversity. Now they just have to learn how to capitalize on them more.

In the future, those countries will lead that reach a healthy balance between business, government and citizens. This requires networked thinking and the establishment of an information, innovation, product and service "ecosystem." In order to work well, it is not only important to create opportunities for participation, but also to support diversity. Because there is no way to determine the best goal function: should we optimize the gross national product per capita or sustainability? Power or peace? Happiness or life expectancy? Often enough, what would have been better is only known after the fact. By allowing the pursuit of various different goals, a pluralistic society is better able to cope with the range of unexpected challenges to come.

Centralized, top-down control is a solution of the past, which is only suitable for systems of low complexity. Therefore, federal systems and majority decisions are the solutions of the present. With economic and cultural evolution, social complexity will continue to rise. Therefore, the solution for the future is collective intelligence. This means that citizen science, crowdsourcing and online discussion platforms are eminently important new approaches to making more knowledge, ideas and resources available.

Collective intelligence requires a high degree of diversity. This is, however, being reduced by today's personalized information systems, which reinforce trends.

Sociodiversity is as important as biodiversity. It fuels not only collective intelligence and innovation, but also resilience—the ability of our society to cope with unexpected shocks. Reducing sociodiversity often also reduces the functionality and performance of an economy and society. This is the reason why totalitarian regimes often end up in conflict with their neighbors. Typical long-term consequences are political instability and war, as have occurred time and again throughout history. Pluralism and participation are therefore not to be seen primarily as concessions to citizens, but as functional prerequisites for thriving, complex, modern societies.

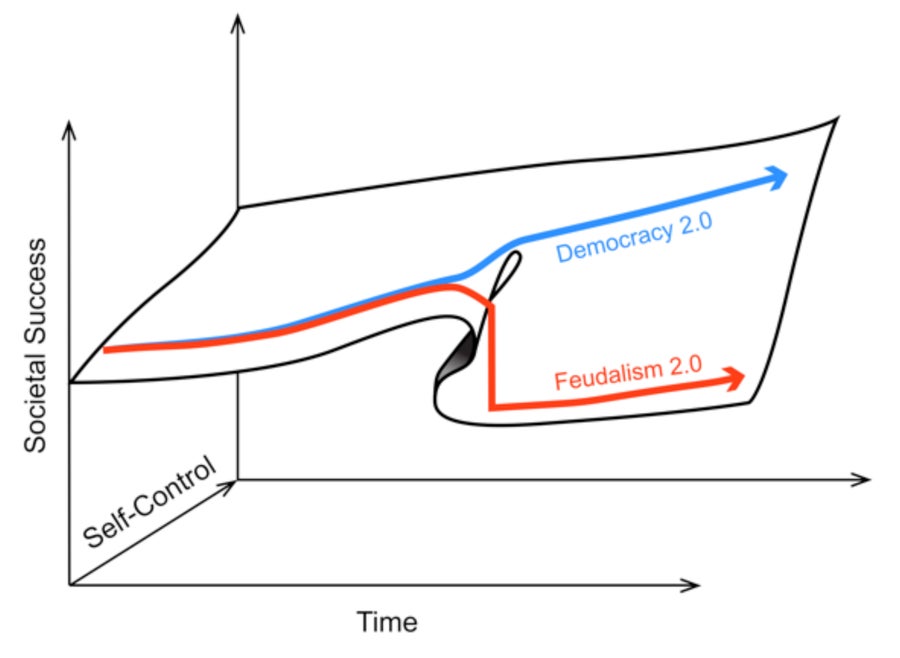

In summary, it can be said that we are now at a crossroads (see Fig. 2). Big data, artificial intelligence, cybernetics and behavioral economics are shaping our society—for better or worse. If such widespread technologies are not compatible with our society's core values, sooner or later they will cause extensive damage. They could lead to an automated society with totalitarian features. In the worst case, a centralized artificial intelligence would control what we know, what we think and how we act. We are at the historic moment, where we have to decide on the right path—a path that allows us all to benefit from the digital revolution. Therefore, we urge to adhere to the following fundamental principles:

1. to increasingly decentralize the function of information systems;

2. to support informational self-determination and participation;

3. to improve transparency in order to achieve greater trust;

4. to reduce the distortion and pollution of information;

5. to enable user-controlled information filters;

6. to support social and economic diversity;

7. to improve interoperability and collaborative opportunities;

8. to create digital assistants and coordination tools;

9. to support collective intelligence, and

10. to promote responsible behavior of citizens in the digital world through digital literacy and enlightenment.

Following this digital agenda we would all benefit from the fruits of the digital revolution: the economy, government and citizens alike. What are we waiting for?

A Strategy for the Digital Age

Big data and artificial intelligence are undoubtedly important innovations. They have an enormous potential to catalyze economic value and social progress, from personalized healthcare to sustainable cities. It is totally unacceptable, however, to use these technologies to incapacitate the citizen. Big nudging and citizen scores abuse centrally collected personal data for behavioral control in ways that are totalitarian in nature. This is not only incompatible with human rights and democratic principles, but also inappropriate to manage modern, innovative societies. In order to solve the genuine problems of the world, far better approaches in the fields of information and risk management are required. The research area of responsible innovation and the initiative ”Data for Humanity” (see "Big Data for the benefit of society and humanity") provide guidance as to how big data and artificial intelligence should be used for the benefit of society.

What can we do now? First, even in these times of digital revolution, the basic rights of citizens should be protected, as they are a fundamental prerequisite of a modern functional, democratic society. This requires the creation of a new social contract, based on trust and cooperation, which sees citizens and customers not as obstacles or resources to be exploited, but as partners. For this, the state would have to provide an appropriate regulatory framework, which ensures that technologies are designed and used in ways that are compatible with democracy. This would have to guarantee informational self-determination, not only theoretically, but also practically, because it is a precondition for us to lead our lives in a self-determined and responsible manner.

There should also be a right to get a copy of personal data collected about us. It should be regulated by law that this information must be automatically sent, in a standardized format, to a personal data store, through which individuals could manage the use of their data (potentially supported by particular AI-based digital assistants). To ensure greater privacy and to prevent discrimination, the unauthorised use of data would have to be punishable by law. Individuals would then be able to decide who can use their information, for what purpose and for how long. Furthermore, appropriate measures should be taken to ensure that data is securely stored and exchanged.

Sophisticated reputation systems considering multiple criteria could help to increase the quality of information on which our decisions are based. If data filters and recommendation and search algorithms would be selectable and configurable by the user, we could look at problems from multiple perspectives, and we would be less prone to manipulation by distorted information.

In addition, we need an efficient complaints procedure for citizens, as well as effective sanctions for violations of the rules. Finally, in order to create sufficient transparency and trust, leading scientific institutions should act as trustees of the data and algorithms that currently evade democratic control. This would also require an appropriate code of conduct that, at the very least, would have to be followed by anyone with access to sensitive data and algorithms—a kind of Hippocratic Oath for IT professionals.

Furthermore, we would require a digital agenda to lay the foundation for new jobs and the future of the digital society. Every year we invest billions in the agricultural sector and public infrastructure, schools and universities—to the benefit of industry and the service sector.

Which public systems do we therefore need to ensure that the digital society becomes a success? First, completely new educational concepts are needed. This should be more focused on critical thinking, creativity, inventiveness and entrepreneurship than on creating standardised workers (whose tasks, in the future, will be done by robots and computer algorithms). Education should also provide an understanding of the responsible and critical use of digital technologies, because citizens must be aware of how the digital world is intertwined with the physical one. In order to effectively and responsibly exercise their rights, citizens must have an understanding of these technologies, but also of what uses are illegitimate. This is why there is all the more need for science, industry, politics, and educational institutions to make this knowledge widely available.

Secondly, a participatory platform is needed that makes it easier for people to become self-employed, set up their own projects, find collaboration partners, market products and services worldwide, manage resources and pay tax and social security contributions (a kind of sharing economy for all). To complement this, towns and even villages could set up centers for the emerging digital communities (such as fab labs), where ideas can be jointly developed and tested for free. Thanks to the open and innovative approach found in these centers, massive, collaborative innovation could be promoted.

Particular kinds of competitions could provide additional incentives for innovation, help increase public visibility and generate momentum for a participatory digital society. They could be particularly useful in mobilising civil society to ensure local contributions to global problems solving (for example, by means of "Climate Olympics"). For instance, platforms aiming to coordinate scarce resources could help unleash the huge potential of the circular and sharing economy, which is still largely untapped.

With the commitment to an open data strategy, governments and industry would increasingly make data available for science and public use, to create suitable conditions for an efficient information and innovation ecosystem that keeps pace with the challenges of our world. This could be encouraged by tax cuts, in the same way as they were granted in some countries for the use of environmentally friendly technologies.

Thirdly, building a "digital nervous system," run by the citizens, could open up new opportunities of the Internet of Things for everyone and provide real-time data measurements available to all. If we want to use resources in a more sustainable way and slow down climate change, we need to measure the positive and negative side effects of our interactions with others and our environment. By using appropriate feedback loops, systems could be influenced in such a way that they achieve the desired outcomes by means of self-organization.

For this to succeed we would need various incentive and exchange systems, available to all economic, political and social innovators. This could create entirely new markets and, therefore, also the basis for new prosperity. Unleashing the virtually unlimited potential of the digital economy would be greatly promoted by a pluralistic financial system (for example, functionally differentiated currencies) and new regulations for the compensation for inventions.

To better cope with the complexity and diversity of our future world and to turn it into an advantage, we will require personal digital assistants. These digital assistants will also benefit from developments in the field of artificial intelligence. In the future it can be expected that numerous networks combining human and artificial intelligence will be flexibly built and reconfigured, as needed. However, in order for us to retain control of our lives, these networks should be controlled in a distributed way. In particular, one would also have to be able to log in and log out as desired.

Democratic Platforms

A "Wikipedia of Cultures" could eventually help to coordinate various activities in a highly diverse world and to make them compatible with each other. It would make the mostly implicit success principles of the world's cultures explicit, so that they could be combined in new ways. A "Cultural Genome Project" like this would also be a kind of peace project, because it would raise public awareness for the value of sociocultural diversity. Global companies have long known that culturally diverse and multidisciplinary teams are more successful than homogeneous ones. However, the framework needed to efficiently collate knowledge and ideas from lots of people in order to create collective intelligence is still missing in many places. To change this, the provision of online deliberation platforms would be highly useful. They could also create the framework needed to realize an upgraded, digital democracy, with greater participatory opportunities for citizens. This is important, because many of the problems facing the world today can only be managed with contributions from civil society.

Further Reading:

ACLU: Orwellian Citizen Score, China's credit score system, is a warning for Americans, http://www.computerworld.com/article/2990203/security/aclu-orwellian-citizen-score-chinas-credit-score-system-is-a-warning-for-americans.html

Big data, meet Big Brother: China invents the digital totalitarian state. The worrying implications of its social-credit project. The Economist (December 17, 2016).

Harris, S. The Social Laboratory, Foreign Policy (29 July 2014), http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/07/29/the-social-laboratory/

Tong, V.J.C. Predicting how people think and behave, International Innovation, http://www.internationalinnovation.com/predicting-how-people-think-and-behave/

Volodymyr, M., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., et al.: Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. In: Nature, 518, S. 529-533, 2015.

Frey, B. S. und Gallus, J.: Beneficial and Exploitative Nudges. In: Economic Analysis of Law in European Legal Scholarship. Springer, 2015.

Gigerenzer, G.: On the Supposed Evidence for Libertarian Paternalism. In: Review of Philosophy and Psychology 6(3), S. 361-383, 2015.

Grassegger, H. and Krogerus, M. Ich habe nur gezeigt, dass es die Bombe gibt [I have only shown the bomb exists]. Das Magazin (3. Dezember 2016) https://www.dasmagazin.ch/2016/12/03/ich-habe-nur-gezeigt-dass-es-die-bombe-gibt/

Hafen, E., Kossmann, D. und Brand, A.: Health data cooperatives—citizen empowerment. In: Methods of Information in Medicine 53(2), S. 82–86, 2014.

Helbing, D.: The Automation of Society Is Next: How to Survive the Digital Revolution. CreateSpace, 2015.

Helbing, D.: Thinking Ahead—Essays on Big Data, Digital Revolution, and Participatory Market Society. Springer, 2015.

Helbing, D. und Pournaras, E.: Build Digital Democracy. In: Nature 527, S. 33-34, 2015.

van den Hoven, J., Vermaas, P.E. und van den Poel, I.: Handbook of Ethics, Values and Technological Design. Springer, 2015.

Zicari, R. und Zwitter, A.: Data for Humanity: An Open Letter. Frankfurt Big Data Lab, 13.07.2015. Zwitter, A.: Big Data Ethics. In: Big Data & Society 1(2), 2014.

Figure 1: Digital growth. Source: Dirk Helbing

Thanks to Big Data, we can now take better, evidence-based decisions. However, the principle of top-down control increasingly fails, since the complexity of society grows in an explosive way as we go on networking our world. Distributed control approaches will become ever more important. Only by means of collective intelligence will it be possible to find appropriate solutions to the complexity challenges of our world.

Figure 2: At the digital crossroads. Source: Dirk Helbing

Our society is at a crossroads: If ever more powerful algorithms would be controlled by a few decision-makers and reduce our self-determination, we would fall back in a Feudalism 2.0, as important historical achievements would be lost. Now, however, we have the chance to choose the path to digital democracy or democracy 2.0, which would benefit us all (see also https://vimeo.com/147442522 ).

Spotlight on China: Is this what the Future of Society looks like?

How would behavioural and social control impact our lives? The concept of a Citizen Score, which is now being implemented in China, gives an idea. There, all citizens are rated on a one-dimensional ranking scale. Everything they do gives plus or minus points. This is not only aimed at mass surveillance. The score depends on an individual's clicks on the Internet and their politically-correct conduct or not, and it determines their credit terms, their access to certain jobs, and travel visas. Therefore, the Citizen Score is about behavioural and social control. Even the behaviour of friends and acquaintances affects this score, i.e. the principle of clan liability is also applied: everyone becomes both a guardian of virtue and a kind of snooping informant, at the same time; unorthodox thinkers are isolated. Were similar principles to spread in democratic countries, it would be ultimately irrelevant whether it was the state or influential companies that set the rules. In both cases, the pillars of democracy would be directly threatened:

The tracking and measuring of all activities that leave digital traces would create a "naked" citizen, whose human dignity and privacy would progressively be degraded.

Decisions would no longer be free, because a wrong choice from the perspective of the government or company defining the criteria of the points system would have negative consequences. The autonomy of the individual would, in principle, be abolished.

Each small mistake would be punished and no one would be unsuspicious. The principle of the presumption of innocence would become obsolete. Predictive Policing could even lead to punishment for violations that have not happened, but are merely expected to occur.

As the underlying algorithms cannot operate completely free of error, the principle of fairness and justice would be replaced by a new kind of arbitrariness, against which people would barely be able to defend themselves.

If individual goals were externally set, the possibility of individual self-development would be eliminated and, thereby, democratic pluralism, too.

Local culture and social norms would no longer be the basis of appropriate, situation-dependent behaviour.

The control of society with a one-dimensional goal function would lead to more conflicts and, therefore, to a loss of security. One would have to expect serious instability, as we have seen it in our financial system.

Such a control of society would turn away from self-responsible citizens to individuals as underlings, leading to a Feudalism 2.0. This is diametrically opposed to democratic values. It is therefore time for an Enlightenment 2.0, which would feed into a Democracy 2.0, based on digital self-determination. This requires democratic technologies: information systems, which are compatible with democratic principles - otherwise they will destroy our society.

"Big Nudging" - Ill-Designed for Problem Solving

He who has large amounts of data can manipulate people in subtle ways. But even benevolent decision-makers may do more wrong than right, says Dirk Helbing.

Proponents of Nudging argue that people do not take optimal decisions and it is, therefore, necessary to help them. This school of thinking is known as paternalism. However, Nudging does not choose the way of informing and persuading people. It rather exploits psychological weaknesses in order to bring us to certain behaviours, i.e. we are tricked. The scientific approach underlying this approach is called "behaviorism", which is actually long out of date.

Decades ago, Burrhus Frederic Skinner conditioned rats, pigeons and dogs by rewards and punishments (for example, by feeding them or applying painful electric shocks). Today one tries to condition people in similar ways. Instead of in a Skinner box, we are living in a "filter bubble": with personalized information our thinking is being steered. With personalized prices, we may be even punished or rewarded, for example, for (un)desired clicks on the Internet. The combination of Nudging with Big Data has therefore led to a new form of Nudging that we may call "Big Nudging". The increasing amount of personal information about us, which is often collected without our consent, reveals what we think, how we feel and how we can be manipulated. This insider information is exploited to manipulate us to make choices that we would otherwise not make, to buy some overpriced products or those that we do not need, or perhaps to give our vote to a certain political party.

However, Big Nudging is not suitable to solve many of our problems. This is particularly true for the complexity-related challenges of our world. Although already 90 countries use Nudging, it has not reduced our societal problems - on the contrary. Global warming is progressing. World peace is fragile, and terrorism is on the rise. Cybercrime explodes, and also the economic and debt crisis is not solved in many countries.

There is also no solution to the inefficiency of financial markets, as Nudging guru Richard Thaler recently admitted. In his view, if the state would control financial markets, this would rather aggravate the problem. But why should one then control our society in a top-down way, which is even more complex than a financial market? Society is not a machine, and complex systems cannot be steered like a car. This can be understood by discussing another complex system: our bodies. To cure diseases, one needs to take the right medicine at the right time in the right dose. Many treatments also have serious side and interaction effects. The same, of course, is expected to apply to social interventions by Big Nudging. Often is not clear in advance what would be good or bad for society. 60 percent of the scientific results in psychology are not reproducible. Therefore, chances are to cause more harm than good by Big Nudging.

Furthermore, there is no measure, which is good for all people. For example, in recent decades, we have seen food advisories changing all the time. Many people also suffer from food intolerances, which can even be fatal. Mass screenings for certain kinds of cancer and other diseases are now being viewed quite critically, because the side effects of wrong diagnoses often outweigh the benefits. Therefore, if one decided to use Big Nudging, a solid scientific basis, transparency, ethical evaluation and democratic control would be really crucial. The measures taken would have to guarantee statistically significant improvements, and the side effects would have to be acceptable. Users should be made aware of them (in analogy to a medical leaflet), and the treated persons would have to have the last word.

In addition, applying one and the same measure to the entire population would not be good. But far too little is known to take appropriate individual measures. Not only is it important for society to apply different treatments in order to maintain diversity, but correlations (regarding what measure to take in what particular context) matter as well. For the functioning of society it is essential that people apply different roles, which are fitting to the respective situation they are in. Big Nudging is far from being able to deliver this.

Current Big-Data-based personalization rather creates new problems such as discrimination. For instance, if we make health insurance rates dependent on certain diets, then Jews, Muslims and Christians, women and men will have to pay different rates. Thus, a bunch of new problems is arising.

Richard Thaler is, therefore, not getting tired to emphasize that Nudging should only be used in beneficial ways. As a prime example, how to use Nudging, he mentions a GPS-based route guidance system. This, however, is turned on and off by the user. The user also specifies the respective goal. The digital assistant then offers several alternatives, between which the user can freely choose. After that, the digital assistant supports the user as good as it can in reaching the goal and in making better decisions. This would certainly be the right approach to improve people's behaviours, but today the spirit of Big Nudging is quite different from this.

Digital Self-Determination by Means of a “Right to a Copy”

by Ernst Hafen

Europe must guarantee citizens a right to a digital copy of all data about them (Right to a Copy), says Ernst Hafen. A first step towards data democracy would be to establish cooperative banks for personal data that are owned by the citizens rather than by corporate shareholders.

Medicine can profit from health data. However, access to personal data must be controlled the persons (the data subjects) themselves. The “Right to a Copy” forms the basis for such a control.

In Europe, we like to point out that we live in free, democratic societies. We have almost unconsciously become dependent on multinational data firms, however, whose free services we pay for with our own data. Personal data—which is now sometimes referred to as a “new asset class” or the oil of the 21st Century—is greatly sought after. However, thus far nobody has managed to extract the maximum use from personal data because it lies in many different data sets. Google and Facebook may know more about our health than our doctor, but even these firms cannot collate all of our data, because they rightly do not have access to our patient files, shopping receipts, or information about our genomic make-up. In contrast to other assets, data can be copied with almost no associated cost. Every person should have the right to obtain a copy of all their personal data. In this way, they can control the use and aggregation of their data and decide themselves whether to give access to friends, another doctor, or the scientific community.

The emergence of mobile health sensors and apps means that patients can contribute significant medical insights. By recording their bodily health on their smartphones, such as medical indicators and the side effects of medications, they supply important data which make it possible to observe how treatments are applied, evaluate health technologies, and conduct evidence-based medicine in general. It is also a moral obligation to give citizens access to copies of their data and allow them to take part in medical research, because it will save lives and make health care more affordable.

European countries should copper-fasten the digital self-determination of their citizens by enshrining the “Right to a Copy” in their constitutions, as has been proposed in Switzerland. In this way, citizens can use their data to play an active role in the global data economy. If they can store copies of their data in non-profit, citizen-controlled, cooperative institutions, a large portion of the economic value of personal data could be returned to society. The cooperative institutions would act as trustees in managing the data of their members. This would result in the democratization of the market for personal data and the end of digital dependence.

Democratic Digital Society

Citizens must be allowed to actively participate

In order to deal with future technology in a responsible way, it is necessary that each one of us can participate in the decision-making process, argues Bruno S. Frey from the University of Basel

How can responsible innovation be promoted effectively? Appeals to the public have little, if any, effect if the institutions or rules shaping human interactions are not designed to incentivize and enable people to meet these requests.

Several types of institutions should be considered. Most importantly, society must be decentralized, following the principle of subsidiarity. Three dimensions matter.

Spatial decentralization consists in vibrant federalism. The provinces, regions and communes must be given sufficient autonomy. To a large extent, they must be able to set their own tax rates and govern their own public expenditure.

Functional decentralization according to area of public expenditure (for example education, health, environment, water provision, traffic, culture etc) is also desirable. This concept has been developed through the proposal of FOCJ, or “Functional, Overlapping and Competing Jurisdictions”.

Political decentralization relating to the division of power between the executive (government), legislative (parliament) and the courts. Public media and academia should be additional pillars.

These types of decentralization will continue to be of major importance in the digital society of the future.

In addition, citizens must have the opportunity to directly participate in decision-making on particular issues by means of popular referenda. In the discourse prior to such a referendum, all relevant arguments should be brought forward and stated in an organized fashion. The various proposals about how to solve a particular problem should be compared and narrowed down to those which seem to be most promising, and integrated insomuch as possible during a mediation process. Finally, a referendum needs to take place, which serves to identify the most viable solution for the local conditions (viable in the sense that it enjoys a diverse range of support in the electorate).

Nowadays, on-line deliberation tools can efficiently support such processes. This makes it possible to consider a larger and more diverse range of ideas and knowledge, harnessing “collective intelligence” to produce better policy proposals.

Another way to implement the ten proposals would be to create new, unorthodox institutions. For example, it could be made compulsory for every official body to take on an “advocatus diaboli”. This lateral thinker would be tasked with developing counter-arguments and alternatives to each proposal. This would reduce the tendency to think along the lines of “political correctness” and unconventional approaches to the problem would also be considered.

Another unorthodox measure would be to choose among the alternatives considered reasonable during the discourse process using random decision-makingmechanisms. Such an approach increases the chance that unconventional and generally disregarded proposals and ideas would be integrated into the digital society of the future.

Bruno S. Frey

Bruno Frey (* 1941) is an academic economist and Permanent Visiting Professor at the University of Basel where he directs the Center for Research in Economics and Well-Being (CREW). He is also Research Director of the Center for Research in Economics, Management and the Arts (CREMA) in Zurich.

Democratic Technologies and Responsible Innovation

When technology determines how we see the world, there is a threat of misuse and deception. Thus, innovation must reflect our values, argues Jeroen van den Hoven.

Germany was recently rocked by an industrial scandal of global proportions. The revelations led to the resignation of the CEO of one of the largest car manufacturers, a grave loss of consumer confidence, a dramatic slump in share price and economic damage for the entire car industry. There was even talk of severe damage to the “Made in Germany” brand. The compensation payments will be in the range of billions of Euro.

The background to the scandal was a situation whereby VW and other car manufacturers used manipulative software which could detect the conditions under which the environmental compliance of a vehicle was tested. The software algorithm altered the behavior of the engine so that it emitted fewer pollutant exhaust fumes under test conditions than in normal circumstances. In this way, it cheated the test procedure. The full reduction of emissions occurred only during the tests, but not in normal use.

In the 21st Century, we urgently need to address the question of how we can implement ethical standards technologically.

Similarly, algorithms, computer code, software, models and data will increasingly determine what we see in the digital society, and what are choices are with regard to health insurance, finance and politics. This brings new risks for the economy and society. In particular, there is a danger of deception.

Thus, it is important to understand that our values are embodied in the things we create. Otherwise, the technological design of the future will determine the shape of our society (“code is law”). If these values are self-serving, discriminatory or contrary to the ideals of freedom and personal privacy, this will damage our society. Thus, in the 21st Century we must urgently address the question of how we can implement ethical standards technologically. The challenge calls for us to “design for value”.

If we lack the motivation to develop the technological tools, science and institutions necessary to align the digital world with our shared values, the future looks very bleak. Thankfully, the European Union has invested in an extensive research and development program for responsible innovation. Furthermore, the EU countries which passed the Lund and Rome Declarations emphasized that innovation needs to be carried out responsibly. Among other things, this means that innovation should be directed at developing intelligent solutions to societal problems, which can harmonize values such as efficiency, security and sustainability. Genuine innovation does not involve deceiving people into believing that their cars are sustainable and efficient. Genuine innovation means creating technologies that can actually satisfy these requirements.

Digital Risk Literacy

Technology needs users who can control it

Rather than letting intelligent technology diminish our brainpower, we should learn to better control it, says Gerd Gigerenzer—beginning in childhood.

The digital revolution provides an impressive array of possibilities: thousands of apps, the Internet of Things, and almost permanent connectivity to the world. But in the excitement, one thing is easily forgotten: innovative technology needs competent users who can control it rather than be controlled by it.

Three examples:

One of my doctoral students sits at his computer and appears to be engrossed in writing his dissertation. At the same time his e-mail inbox is open, all day long. He is in fact waiting to be interrupted. It's easy to recognize how many interruptions he had in the course of the day by looking at the flow of his writing.

An American student writes text messages while driving:

"When a text comes in, I just have to look, no matter what. Fortunately, my phone shows me the text as a pop up at first… so I don't have to do too much looking while I'm driving." If, at the speed of 50 miles per hour, she takes only 2 seconds to glance at her cell phone, she's just driven 48 yards "blind". That young woman is risking a car accident. Her smart phone has taken control of her behavior—as is the case for the 20 to 30 percent of Germans who also text while driving.

During the parliamentary elections in India in 2014, the largest democratic election in the world with over 800 million potential voters, there were three main candidates: N. Modi, A. Kejriwal, and R. Ghandi. In a study, undecided voters could find out more information about these candidates using an Internet search engine. However, the participants did not know that the web pages had been manipulated: For one group, more positive items about Modi popped up on the first page and negative ones later on. The other groups experienced the same for the other candidates. This and similar manipulative procedures are common practice on the Internet. It is estimated that for candidates who appear on the first page thanks to such manipulation, the number of votes they receive from undecided voters increases by 20 percentage points.

In each of these cases, human behavior is controlled by digital technology. Losing control is nothing new, but the digital revolution has increased the possibility of that happening.

What can we do? There are three competing visions. One is techno-paternalism, which replaces (flawed) human judgment with algorithms. The distracted doctoral student could continue readings his emails and use thesis-writing software; all he would need to do is input key information on the topic. Such algorithms would solve the annoying problem of plagiarism scandals by making them an everyday occurrence.

Although still in the domain of science fiction, human judgment is already being replaced by computer programs in many areas. The BabyConnect app, for instance, tracks the daily development of infants—height, weight, number of times it was nursed, how often its diapers were changed, and much more—while newer apps compare the baby with other users' children in a real-time database. For parents, their baby becomes a data vector, and normal discrepancies often cause unnecessary concern.

The second vision is known as "nudging". Rather than letting the algorithm do all the work, people are steered into a particular direction, often without being aware of it. The experiment on the elections in India is an example of that. We know that the first page of Google search results receives about 90% of all clicks, and half of these are the first two results. This knowledge about human behavior is taken advantage of by manipulating the order of results so that the positive ones about a particular candidate or a particular commercial product appear on the first page. In countries such as Germany, where web searches are dominated by one search engine (Google), this leads to endless possibilities to sway voters. Like techno-paternalism, nudging takes over the helm.

But there is a third possibility. My vision is risk literacy, where people are equipped with the competencies to control media rather than be controlled by it. In general, risk literacy concerns informed ways of dealing with risk-related areas such as health, money, and modern technologies. Digital risk literacy means being able to take advantage of digital technologies without becoming dependent on or manipulated by them. That is not as hard as it sounds. My doctoral student has since learned to switch on his email account only three times a day, morning, noon, and evening, so that he can work on his dissertation without constant interruption.

Learning digital self-control needs to begin as a child, at school and also from the example set by parents. Some paternalists may scoff at the idea, stating that humans lack the intelligence and self-discipline to ever become risk literate. But centuries ago the same was said about learning to read and write—which a majority of people in industrial countries can now do. In the same way, people can learn to deal with risks more sensibly. To achieve this, we need to radically rethink strategies and invest in people rather than replace or manipulate them with intelligent technologies. In the 21st century, we need less paternalism and nudging and more informed, critical, and risk-savvy citizens. It's time to snatch away the remote control from technology and take our lives into our own hands.

Ethics: Big data for the common good and for humanity

The power of data can be used for good and bad purposes. Roberto Zicari and Andrej Zwitter have formulated five principles of Big Data Ethics.

by Andrej Zwitter and Roberto Zicari

In recent times there have been a growing number of voices — from tech visionaries like Elon Musk (Tesla Motors), to Bill Gates (Microsoft) and Steve Wozniak (Apple) — warning of the dangers of artificial intelligence (AI). A petition against automated weapon systems was signed by 200,000 people and an open letter recently published by MIT calls for a new, inclusive approach to the coming digital society.

We must realize that big data, like any other tool, can be used for good and bad purposes. In this sense, the decision by the European Court of Justice against the Safe Harbour Agreement on human rights grounds is understandable.

States, international organizations and private actors now employ big data in a variety of spheres. It is important that all those who profit from big data are aware of their moral responsibility. For this reason, the Data for Humanity Initiative was established, with the goal of disseminating an ethical code of conduct for big data use. This initiative advances five fundamental ethical principles for big data users:

1. “Do no harm”. The digital footprint that everyone now leaves behind exposes individuals, social groups and society as a whole to a certain degree of transparency and vulnerability. Those who have access to the insights afforded by big data must not harm third parties.

2. Ensure that data is used in such a way that the results will foster the peaceful coexistence of humanity. The selection of content and access to data influences the world view of a society. Peaceful coexistence is only possible if data scientists are aware of their responsibility to provide even and unbiased access to data.

3. Use data to help people in need. In addition to being economically beneficial, innovation in the sphere of big data could also create additional social value. In the age of global connectivity, it is now possible to create innovative big data tools which could help to support people in need.

4. Use data to protect nature and reduce pollution of the environment. One of the biggest achievements of big data analysis is the development of efficient processes and synergy effects. Big data can only offer a sustainable economic and social future if such methods are also used to create and maintain a healthy and stable natural environment.

5. Use data to eliminate discrimination and intolerance and to create a fair system of social coexistence. Social media has created a strengthened social network. This can only lead to long-term global stability if it is built on the principles of fairness, equality and justice.

To conclude, we would also like to draw attention to how interesting new possibilities afforded by big data could lead to a better future: "As more data become less costly and technology breaks barriers to acquisition and analysis, the opportunity to deliver actionable information for civic purposes grows. This might be termed the 'common good' challenge for big data." (Jake Porway, DataKind). In the end, it is important to understand the turn to big data as an opportunity to do good and as a hope for a better future.

Measuring, Analyzing, Optimizing: When Intelligent Machines Take over Societal Control

In the digital age, machines steer everyday life to a considerable extent already. We should, therefore, think twice before we share our personal data, says expertYvonne Hofstetter

If Norbert Wiener (1894-1964) had experienced the digital era, for him it would have been the land of plenty. “Cybernetics is the science of information and control, regardless of whether the target of control is a machine or a living organism”, the founder of Cybernetics once explained in Hannover, Germany in 1960. In history, the world never produced such amount of data and information as it does today.

Cybernetics, a science asserting ubiquitous importance, makes a strong claim: “Everything can be controlled.” During the 20th century, both the US armed forces and the Soviet Union applied Cybernetics to control their arms’ race. The NATO had deployed so-called C3I systems (Command, Control, Communication and Information), a term for military infrastructure that leans linguistically to Wiener’s book on Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, published in 1948. Control refers to the control of machines as well as of individuals or entire social systems like military alliances, financial markets or, pointing to the 21st century, even the electorate. Its major premise: keeping the world under surveillance to collect data. Connecting people and things to the Internet of Everything is a perfect to way to obtain the required mass data as input to cybernetic control strategies.

With Cybernetics, Wiener proposed a new scientific concept: the closed-loop feedback. Feedback—e.g. the Likes we give, the online comments we make—is a major concept of digitization, too. Does that mean digitization is the most perfect implementation of Cybernetics? When we use smart devices, we are creating a ceaseless data stream disclosing our intentions, geo position or social environment. While we communicate more thoughtlessly than ever online, in the background, an ecosystem of artificial intelligence is evolving. Today, artificial intelligence is the sole technology being able to profile us and draw conclusions about our future behavior.

An automated control strategy, usually a learning machine, analyzes our actual situation and then computes a stimulus that should draw us closer to a more desirable “optimal” state. Increasingly, such controllers govern our daily lives. As digital assistants they help us making decisions in the vast ocean of optionality and intimidating uncertainty. Even Google Search is a control strategy. When typing a keyword, a user reveals his intentions. The Google search engine, in turn, will not just present a list with best hits, but a link list that embodies the highest (financial) value rather for the company than for the user. Doing it that way, i.e. listing corporate offerings at the very top of the search results, Google controls the user’s next clicks. This, the European Union argues, is a misuse.

But is there any way out? Yes, if we disconnected from the cybernetic loop. Just stop responding to a digital stimulus. Cybernetics will fail, if the controllable counterpart steps out of the loop. Yet, we are free to owe a response to a digital controller. However, as digitization further escalates, soon we may have no more choice. Hence, we are called on to fight for our freedom rights—afresh during the digital era and in particular at the rise of intelligent machines.

For Norbert Wiener (1894-1964), the digital era would be a paradise. “Cybernetics is the science of information and control, regardless of whether a machine or a living organism is being controlled”, the founder of cybernetics once said in Hanover, Germany in 1960.

Cybernetics, a science which claims ubiquitous importance makes a strong promise: “Everything is controllable.” During the 20th century, both the US armed forces and the Soviet Union applied cybernetics to control the arms’ race. NATO had deployed so-called C3I systems (Command, Control, Communication and Information), a term for military infrastructure that linguistically leans on Wiener’s book entitled Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine published in 1948. Control refers to the control of machines as well as of individuals or entire societal systems such as military alliances, NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Its basic requirements are: Integrating, collecting data and communicating. Connecting people and things to the Internet of Everything is a perfect way to obtain the required data as input of cybernetic control strategies.

With cybernetics, a new scientific concept was proposed: the closed-loop feedback. Feedback—such as the likes we give or the online comments we make—is another major concept related to digitization. Does this mean that digitization is the most perfect implementation of cybernetics? When we use smart devices, we create an endless data stream disclosing our intentions, geolocation or social environment. While we communicate more thoughtlessly than ever online, in the background, an artificial intelligence (AI) ecosystem is evolving. Today, AI is the sole technology able to profile us and draw conclusions about our future behavior.

An automated control strategy, usually a learning machine, analyses our current state and computes a stimulus that should draw us closer to a more desirable “optimal” state. Increasingly, such controllers govern our daily lives. Such digital assistants help us to make decisions among the vast ocean of options and intimidating uncertainty. Even Google Search is a control strategy. When typing a keyword, a user reveals his intentions. The Google search engine, in turn, presents not only a list of the best hits, but also a list of links sorted according to their (financial) value to the company, rather than to the user. By listing corporate offerings at the very top of the search results, Google controls the user’s next clicks. That is a misuse of Google’s monopoly, the European Union argues.

But is there any way out? Yes, if we disconnect from the cybernetic loop and simply stop responding to the digital stimulus. Cybernetics will fail, if the controllable counterpart steps out of the loop. We should remain discreet and frugal with our data, even if it is difficult. However, as digitization further escalates, soon there may be no more choices left. Hence, we are called on to fight once again for our freedom in the digital era, particularly against the rise of intelligent machines.