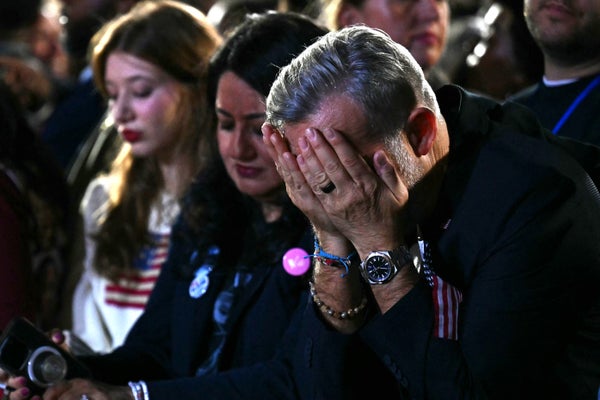

An impassioned election has come to an end, but the emotions of the past few months have not. One of the emotions a lot of people are experiencing is grief, more often associated with death than the voting process. Scientific American spoke with Pauline Boss, an emeritus professor at the University of Minnesota, who spent 45 years as a psychotherapist. She coined the term “ambiguous loss” in her work with wives of soldiers missing in action in the 1970s; more recently, she has applied the idea to what people around the world have experienced during the COVID pandemic.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

What is grief?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Grief is simply the outcome of loss, but there’s a caveat—the criterion for what you lost is that you were attached to it.

You can grieve things that are both clear and unclear. Most of our literature is based on a clear loss—death or the loss of money, things that can be quantified or proven. But there are many, many kinds of losses that remain ambiguous. It’s a term I came up with in the late 1970s that apparently gave a name to a kind of loss that heretofore went unacknowledged. People felt sad; they felt like they wanted to grieve, but nobody would come to their house to comfort them; there were no religious rituals for this kind of loss. There just was no acknowledgment of it.

Now we know there is such thing as ambiguous loss, and I think that’s what people might be experiencing now.

During the COVID pandemic, for example, we had loss of trust in the world as a safe place because of the virus. Many of us baked bread because that was a couple hours of being in control again and having a good outcome. It was certainty, two hours of certainty—that, by the way, is a good way to cope with a situation you can’t control.

Now we have a kind of loss that I think is causing some grief for people who wanted a different outcome of this election. It’s really quite important to understand the feeling. It is a normal response if you’re in the midst of something you didn’t expect and you don’t like, and it came suddenly, unexpectedly. It’s a major loss.

Do we need to change the way we think about emotions such as sadness and anger?

We should normalize the anger and the sadness. I think we jump too quickly to pathologize emotions that are scary. I think you need to be patient with yourself if you’re feeling angry, sad, grieving right now. I think that’s a normal reaction to a surprising outcome and an outcome that, in our view, is going backward and not forward.

So accept your feelings. Know there’s no closure to grief. Know you had a loss. List your losses—I would recommend people actually write them down.

What are some of the psychological losses people might be feeling after the election?

The loss of hopes and dreams and plans that they thought were coming from the other candidate; a loss of certainty in the future that was what they wanted; loss of trust in the world as a safe place; loss of feelings of freedom over your own body; the loss of support for people who have lesser means than the rest of us do; the loss of support for your neighbor and people who are different from you—it’s a grief that remains unresolved.

It’s not like a grief of a person for whom you have a death certificate and a funeral after and rituals of support and comfort. We’re stuck with this. I wrote about it as frozen grief.

What is it that freezes that grief?

A lack of proof—a lack of certainty that you have lost something, because you can’t see it. If someone died, you can see the body or the ashes; you can see the death certificate. There’s something official that says this person you loved and were attached to is now gone, and while that is very sad, you at least have certainty.

With a more abstract kind of loss, there is no proof that you have lost trust in the world except your perception. And if you perceive it to be true, it is true for you—that you’re feeling helpless or powerless that things didn’t go your way.

With frozen grief, you could be immobilized. That’s the danger. Don’t be immobilized. You need to do something active in order to deal with a situation you can’t control. Be active in your neighborhoods at the grassroots level. It will help to be active, not just to sit back and grumble and not just to lash out either. Action is psychologically what helps when you’re feeling helpless.

That sounds like maybe a long-term strategy. You talked about the example of baking bread; would that be a sort of short-term strategy for managing this type of grief?

Absolutely. Short term, you have to do something you can control when you’re in a situation you can’t control. Do something you can control—in your house, in your home, with your family. Go running, listen to music, go to a movie, do something that requires action, that makes your body move. You’ll feel better for that. Go see a neighbor.

Long term, get involved. Get involved with whatever works for change that will bring us closer to the future, not take us backward.

Do you have any words of wisdom for sort of how people can make space for grief over time?

It doesn’t go away. Grief sort of turns itself into sadness, but don’t expect it to ever go away. You may even shed a tear or have an emotion of sadness 20 years from now if you remember this time—and that’s normal. That is normal grief. You do not have to find closure. If you were attached to some thing, some person, some idea, and you lost it, you will carry a sadness about that forever. You will remember it. You won’t forget it, nor should you have to.

When people say to you, “Aren’t you over it yet?” please respond to them and say, the current knowledge is that you don’t have to get over loss and grief. You learn to live with it, and you learn to live with loss by finding a new purpose in it, finding something you can do to change things. You have to find a purpose in your loss, and that purpose should be something active.

I could see someone feeling really cynical and sad saying, like, “If losing things you’re attached to causes grief, then I’m just not going to be attached to things.” Is that actually a healthy response?

No. I’m using attachment rather loosely. In psychology it has a narrower definition, but it is a motivation for our actions and our beliefs and values.

So attachments are really important, even if they do cause you pain sometimes?

That’s right. It’s a good time to sit and reflect on your own life and your own attachments. What do you care about? What do you care about in your own body? What do you care about in your own family, in your neighborhood, in your nation and in the world? I care about climate change not because it will matter in my life so much anymore, given my age, but because I care about my grandchildren and their children.

Is it possible to cultivate more resilience to this kind of grief in the future?

Yes. Increase your tolerance for ambiguity and keep increasing your tolerance for uncertainty. We hate uncertainty in this culture.

There is, in fact, a tolerance for ambiguity scale. It was born out of a scale now called the authoritarian personality scale. [Editor’s Note: That scale was originally developed in the aftermath of World War II by philosopher Theodor Adorno as a response to Nazism. A higher tolerance for ambiguity is related to lower susceptibility to fascist ideologies.]

Change is necessary. If a system of human beings doesn’t change, they die. And right now I think we’re on the precipice of not wanting to change, and that’s not a good thing. That’s going backward. I think we should work toward bringing about change now at the community level, wherever you have power and agency, whatever level you have it at. Maybe it’s just in your family, maybe it’s just in yourself, or maybe it is in your community or state or nation or globally. But work for change—because change is the one thing that will keep us going.

Are there any strategies that people can use to cultivate that tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty in themselves?

Yes. Go see some improvisation at the theater. Go to listen to some jazz music, which is totally improvisation. Do something different that you’ve never done before. Learn a new language; go travel in a foreign country alone. Get to know some people you never knew before that are unlike yourself. Stretch yourself; reach out; do something different. Take a hike on a new path.

I’m not against certainty. I want my accountant to think in binary. And in our sports world, you either win or you lose. That’s a binary. But in human relationships and in our human condition, the binary does not work so well. We’re often in that shadowland of ambiguity and uncertainty.

Is there anything else you want to say about grief people might be feeling right now?

Don’t be afraid of it. Just know that it’s a normal reaction to an outcome you didn’t want or expect. And it doesn’t need to go away, but hopefully it doesn’t immobilize you. The grief is frozen; you yourself shouldn’t be.